Lifestyle

Bracketology a settled national pastime as the 2025 NCAA Tournament arrives

INDIANAPOLIS (AP) — When Bryce Yoder needs a study break this time of year, the college student flips on a TV and attends his favorite March Madness class — bracket science.

The 19-year-old sports management major at Indiana University-Indianapolis studies hard to learn the secrets of picking winners in the nearly dozen NCAA Tournament bracket pools he hopes to enter before Thursday’s first-round games. It takes time, patience and some lucky bounces to get those picks right.

Yoder is hardly alone. Millions of Americans — from hard-core sports junkies to casual fans and school alumni to those with no rooting interest — engage in this annual national pastime by filling out a tourney bracket and seeing how they fare. Winning is possible, though few hold out much hope of a perfect bracket: The NCAA says the odds of that are 1 in 9,223,372,036,854,775,808 if you wing it and a still-absurd 1 in 120.2 billion if you know a bit about hoops.

For players like Yoder, it’s more about proving he’s the best.

“The satisfaction of being right,” he said in explaining why he fills out so many brackets. “Really, it’s about having the best bracket possible, whether that’s with my friends and family or just the leaderboard over a random bunch of people that I’ve never met. I’m just so competitive.”

From online gambling to office pools to family contests, brackets are big business and a big distraction. A study released in 2023 by Challenger, Gray & Christmas, a work outplacement firm, estimated $17.3 billion is lost in productivity during the three-week tourney. A Finance Buzz survey back then also found 36% of employees tune into the games during work hours, and nearly 25% use paid time off or sick days.

Even elective surgery companies now advertise that customers can have mid-March procedures so they can recover — and watch basketball — at the same time.

In the beginning

It seems almost unfathomable today, but brackets meant virtually nothing for about the first 50 years of the NCAA tourney, which dates to 1939 and this year is holding its 86th edition.

During the ‘70s, though, the changes began in earnest.

The NCAA tourney expanded from 25 to 32 teams in 1975, the first year leagues could send two teams. Seeding started in 1978, and the field grew to 40 in 1979 and to 48 in 1980 when organizers dropped the restriction on how many league teams could play.

But the real revolution really with the 1979 title game between Michigan State and Indiana State.

Indiana State’s Larry Bird, left, lies on his back to toss the ball during a scramble with Earvin “Magic” Johnson, right, during NCAA Championship game in Salt Lake City, Utah, March 26, 1979. (AP Photo)

That Magic Johnson-Larry Bird matchup drew a 24.1 television rating, still the tourney record, and it gave everyone a glimpse into what college basketball’s biggest event could become at the same time an 8-year-old boy named Charlie Creme looked into his future.

“I cut the (men’s) bracket out of the newspaper in 1979 and had it on the pantry door in my family’s kitchen,” said Creme, now ESPN’s women’s basketball bracketologist. “I was filling it out, making actual predictions and I couldn’t wait till a game ended and I could run up to the pantry door and advance the next team in the tournament. Within a couple years, I was making my own brackets with big pieces of oak tag (paper) and a pencil and a ruler.”

Soon, he’d have company as the tourney grew.

America’s first all-sports network, ESPN, broadcast the 16 first-round games, 12 on tape delay, in 1980. CBS wrested the broadcast rights away from NBC in 1982 with a three-year deal for $16 million annually and the promise of expanded coverage including the first televised selection show.

Suddenly, brackets mattered and broadcasters such as Dick Vitale stoked long debates over which teams belonged, which did not and who would win games. Live, daily telecasts on ESPN spurred interest, too, heading into 1985, the first 64-team field and introduced a future NCAA executive to fill out the bracket.

“The first one I remember filling out was 1985,” said Dan Gavitt, the son of Big East co-founder Dave Gavitt and now the NCAA senior vice president for basketball. “I had four Big East teams in the Final Four and I was right on three of them. Boston College got beat by Memphis in in the regional finals.”

Gavitt, like Creme, was hooked and brackets became fashionable.

Could it happen again on the women’s side? Perhaps.

After seeing ticket sales, television ratings and coverage of the sport soar in the last few years with more to come thanks to stars such as Paige Bueckers, Hannah Hidalgo and JuJu Watkins, Creme thinks women’s brackets are on a similar trajectory.

“We might be seeing 1985-95,” Creme said. “Star players in the men’s game back then, stuck around longer. Right now we’re in that period where Caitlin Clark played four years in college and as the rules stand now, JuJu Watkins has to play four years and Paige could if she wanted — she’s not going to — but could stick around another year. That’s where the men’s game was in that period.”

Upset city, baby

In its infancy, the bracket phenomenon was geared to teenagers and college students like Yoder who watched multiple games.

Soon, office pools and games among family members with entry fees and prize money became popular, too. In some cases, all you did was pluck a name out of a hat.

Back then, the NCAA frowned on such practices, labeling it gambling. Today, the NCAA runs its own online bracket game as part of its “fan engagement.”

Still, the prize pool only fueled interest. So did the 1980s national championship games that became must-see TV — and the upset factor.

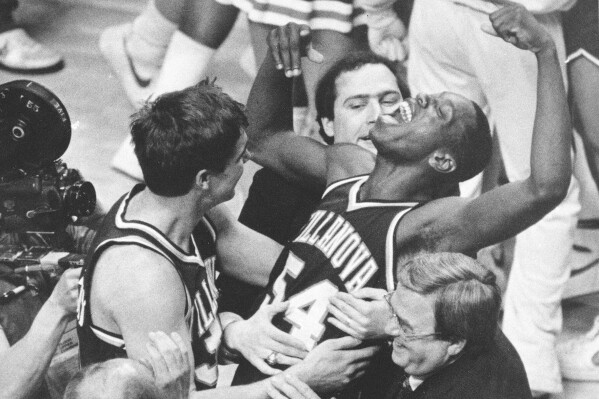

FILE – In this April 1, 1985, file photo, Villanova’s Ed Pinckney (54) yells out as he is surrounded by teammates after defeating Georgetown 66-64 in the NCAA college basketball Final Four championship game, in Lexington, Ky. (AP Photo/Gary Landers, File)

From surprising title runs by North Carolina State in 1983 and Villanova in 1985 to Princeton’s near-upset of Georgetown in 1989, it seemed every team was in the mix and nobody would pick all the winners.

“There will never be a perfect bracket,” ESPN men’s basketball bracketologist Joe Lunardi said. “That’s just not going to happen. When Warren Buffet offered $10 million for perfect bracket, he knew he wasn’t going to pay that out.”

Those daunting odds haven’t stopped anyone from filling out brackets.

“If I feel really strongly about a game, I’ll probably pick the same outcome more times than not,” Yoder said, referring to how he handles multiple brackets. “But I try to throw some silly type of stuff that wouldn’t necessarily have a good chance of happening, like upsets, because that’s just naturally going to happen.”

The tools

In this May 27, 2010 file photo, President Barack Obama looks over the bracket with Duke University basketball Coach Mike Krzyzewski in the Rose Garden of the White House in Washington, where he honored the team. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon, File)

Figuring out how to pick teams and games has evolved the years.

Selection committee members use tangible measures such as wins and losses, strength of schedule and NET rankings to round out the 68-team field. Other measures include quad victories, which vary in how they’re compiled and applied. In an era of analytics, sites such as kenpom.com have become regular components for hard-core and casual fans.

The NCAA certainly is paying attention.

Gavitt said he filled out brackets in the early years of the NET just to see how reliable the rankings were to results And when the topic of expansion is broached, NCAA officials look to see how the potential new bracket would fit on a single printed page.

The question, of course, is how far can this go and whether artificial intelligence can become the next big thing when it comes to picking winners.

“If AI did it, then the analysis would not be as much fun or as interesting,” Creme said. “I don’t know that the NCAA would ever go that far. I kind of hope not because I like the human element. If it’s eliminated, if we know the AI formula, then it’s sort of over.”

___

AP March Madness bracket: https://apnews.com/hub/ncaa-mens-bracket and coverage: https://apnews.com/hub/march-madness

Get poll alerts and updates on the AP Top 25 throughout the season. Sign up here.

Lifestyle

Emmys 2025: Where to stream this year’s top nominees

Now that the Primetime Emmy Awards nominations have been announced, you’ve got two months to catch up on some of the year’s most-acclaimed shows.

Some binges may take longer than others, but the list below should help you choose what to watch and how long it should take to catch up. For those looking for the most bang for their streaming buck, HBO Max has the most shows nominated this year.

Comedian Nate Bargatze hosts the 77th Primetime Emmy Awards on Sept. 14 on CBS and streaming on Paramount+.

——

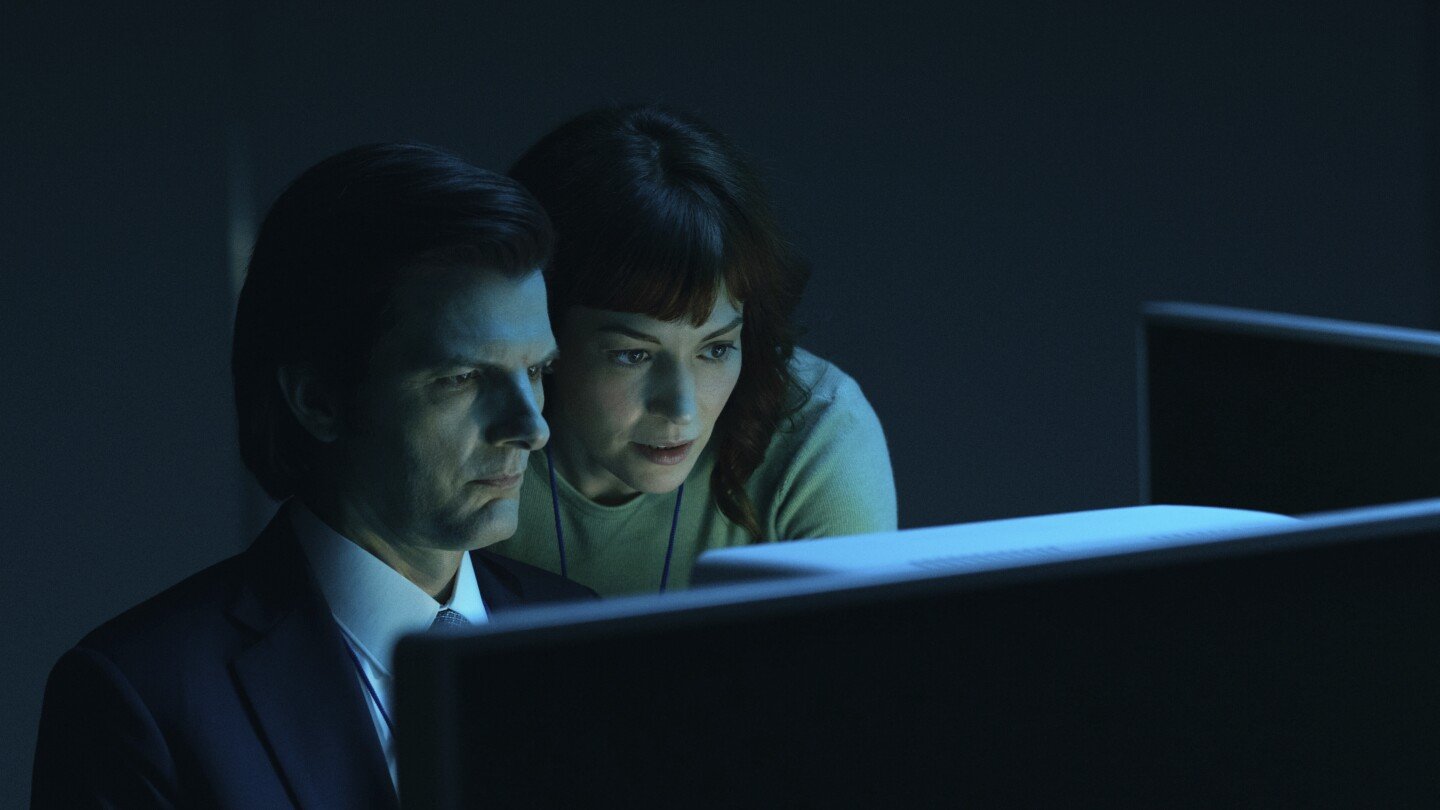

“Severance” (27 Emmy Nominations): Streaming on Apple TV+

In “Severance,” Adam Scott’s character Mark works for a corporation that implants a chip in its employees’ brains, so they forget about their outside lives while at work and have no memory of their work when they’re off. Mark begins to question his work life when he encounters a colleague outside who knows who he is. Beyond the dinner party conversation of “would you want that microchip,” the show has become an obsession for fans who analyze scenes, look for clues and try to make sense of its many mysteries.

Total No. of seasons: 2

Total No. of episodes: in season 2: 10

Total season 2 binge time: 8 hours and 29 minutes

Total series binge time: 15 hours and 29 minutes

This image released by Apple TV+ shows Seth Rogen, left, and Catherine O’Hara in a scene from “The Studio.” (Apple TV+ via AP)

“The Studio” (23 Emmy nominations): Streaming on Apple TV+

Cinephile Matt Remick (Seth Rogen) has been promoted to his dream job as the head of a fictional Hollywood studio. Juggling the desire to create art with marketing and focus groups makes the work harder and more stressful than he imagined. “The Studio” has similarities to “Curb Your Enthusiasm” and “Entourage” with awkward scenarios and actors and industry types including Martin Scorsese and Ron Howard playing heightened versions of themselves.

Total No. of episodes: 10

Total binge time: 5 hours and 15 minutes

This image released by HBO shows Sam Nivola, from left, Sarah Catherine Hook, and Patrick Schwarzenegger in a scene from “The White Lotus.” (Fabio Lovino/HBO via AP)

“The White Lotus” (23 Emmy Nominations): Streaming on HBO Max

A dark comedy anthology about privileged guests and the staff at a luxury resort, this year’s season took viewers to Thailand. The series often has themes of wealth, power, greed, lust and self-worth. Each of the show’s three seasons has also had a murder mystery, with a pair of characters from season one making a tense return.

Total No. of episodes: 21

Total No. of season 3 episodes: 8

Total season 3 binge time: 8 hours and 36 minutes

Total binge time: 21 hours and 55 minutes

This image released by HBO shows Bella Ramsey, left, and Pedro Pascal in a scene from “The Last of Us.” (HBO via AP)

“The Last of Us” (16 Emmy Nominations): Streaming on HBO Max

“The Last of Us” is set in a postapocalyptic U.S. where Pedro Pascal’s character Joel is hired to smuggle a girl named Ellie (Bella Ramsey) across the country. They’re two decades into a pandemic that turns the infected into mutated creatures and Ellie may be key to a vaccine.

Total No. of seasons: 2

Total No. of season 2 episodes: 7

Total season 2 binge time: 6 hours and 21 minutes

Total series binge time: 15 hours and 7 minutes

“Andor” (14 Emmy nominations): Streaming on Disney+

Diego Luna plays out Rebel spy Cassian Andor’s radicalization against the Galactic Empire leading up to “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story” prequel series. Created by showrunner Tony Gilroy, the two season run — which put emotions under the spotlight in this sci-fi story — took the characters right up to the events of the Gilroy-written “Rogue One.”

Total No. of seasons: 2

Total No. of episodes in season 2: 12

Total season 2 binge time: 10 hours, 19 minutes

Total series binge time: 19 hours, 49 minutes

This image released by HBO shows Jean Smart in a scene from “Hacks.” (HBO via AP)

“Hacks” (14 Emmy nominations): Streaming on HBO Max

A female comedian of a certain age (played by Jean Smart ) and a Gen Z comedy writer (Hannah Einbinder) are frenemies and each other’s muses in “Hacks.” Smart has won an outstanding lead actress Emmy for each of the show’s first three seasons. Einbinder, who is also a standup comic, has been nominated three times in the supporting actress category. Season 4 debuted in April.

Total No. of episodes: 37

Total No. of Season 4 episodes: 10

Total season 4 binge time: 5 hours and 33 minutes

Total series binge time: 20 hours and 14 minutes

“Adolescence” (13 Emmy nominations): Streaming on Netflix

Thirteen-year-old Jamie Miller (played by newcomer Owen Cooper) is arrested in the stabbing death of a schoolmate. His family struggles with this new reality as investigators and a psychologist piece together what led up to the crime. Each episode was filmed in one continuous shot, with the best one chosen for air. The cast and crew had extensive rehearsals ahead of time, blocking out the camera’s movements — and sometimes requiring it to be passed off between operators.

Total No. of episodes: 4

Total binge time: 3 hours and 48 minutes

This image released by Max shows Noah Wyle in a scene from “The Pitt.” (Warrick Page/MAX via AP)

“The Pitt” (13 Emmy Nominations): Streaming on HBO Max

Noah Wyle puts his stethoscope back on and returns to the ER (not THAT “ER,”) in “The Pitt,” short for Pittsburgh Trauma Medical Hospital. Wyle stars as an emergency room physician who goes by Dr. Robby. We meet him in the pilot as he’s beginning his workday. Each of the 15 episodes is one hour of that shift treating patients usually in need of critical care while navigating American health care challenges like low budgets, staffing shortages and red tape from insurance policies.

Total No. of episodes: 15

Total binge time: 12 hours and 7 minutes

“The Bear” (13 Emmy Nominations): Streaming on Hulu

An award-winning chef who has worked in some of the world’s greatest restaurants attempts to transform his family’s sandwich shop in Chicago to a fine-dining establishment in FX’s “The Bear.” The show, now in its fourth season, has been a star-making vehicle for its cast like Jeremy Allen White, Ayo Edebiri, Ebon Moss-Bachrach and Liza Colón-Zayas.

Total No. of seasons: 4

Total No. of episodes in season 4: 10

Total season 4 binge time: 6 hours and 9 minutes

Total series binge time: 21 hours and 50 minutes

“Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez story” (11 Emmy nominations): Streaming on Netflix

A true crime dramatization of the story of Lyle and Erik Menendez, privileged brothers living in Beverly Hills who murdered their parents, Jose and Kitty in 1989. The brothers said it was self-defense because Jose was sexually abusive. They were found guilty and sentenced to life in prison but recently became eligible for parole.

The limited series presented the case from multiple perspectives. It also introduced viewers to new talents Nicholas Alexander Chavez and Cooper Koch, who played Lyle and Erik.

Total No. of episodes: 9

Total binge time: 7 hours and 50 minutes

“Dying for Sex” (9 Emmy Nominations): Streaming on Hulu

Liz Meriwether (“New Girl”) helped adapt a popular podcast about TV personality Nikki Boyer’s experience into this limited series for FX. Michelle Williams stars as Molly, who is diagnosed with terminal cancer and decides to live out her days seeking pleasure. The title and premise may sound risqué, but the show is fundamentally about the love story between Molly and her best friend Nikki (Jenny Slate) who puts her life on hold to be a caregiver.

Total No. of episodes: 8

Total binge time: 4 hours and 6 minutes

“Only Murders in the Building” (7 Emmy nominations): Streaming on Hulu

Steve Martin, Martin Short and Selena Gomez play residents of the same Manhattan apartment building who start a true crime podcast when there’s a murder on the premises.

Total No. of seasons: 4

Total No. of season 4 episodes: 10

Total season 4 binge time: 5 hours and 27 minutes

Total series binge time: 22 hours and 46 minutes

This image released by Apple TV+ shows Harrison Ford, left, and Jason Segel in a scene from “Shrinking.” (Beth Dubber/Apple TV+ via AP)

“Shrinking” (7 Emmy Nominations): Streaming on Apple TV+

A widowed therapist (Jason Segel) adjusts to single life and raising a teenager thanks to friends, neighbors, colleagues and his unconventional methods with patients. The show features a standout cast that includes Harrison Ford, Jessica Williams, Christa Miller, Michael Urie and Luke Tennie. Segel created the series with Bill Lawrence (“Scrubs,” “Cougar Town”) and Emmy winner Brett Goldstein, who played Roy Kent on “Ted Lasso.”

Total No. of seasons: 2

Total No. of episodes in season 2: 12

Total season 2 binge time: 7 hours and 13 minutes

Total series binge time: 12 hours and 35 minutes

“What We Do in the Shadows” (6 Emmy nominations): Streaming on Hulu

A documentary crew follows four vampires living together in Long Island, New York, The roomies often bicker amongst each other and have ridiculous interactions with humans and modern life. In Season 6, we meet a sixth vampire housemate named Jerry. He went to sleep in 1976 and was supposed to be woken up 20 years later, but everybody forgot about him. The show is based on a film of the same name that was directed by Jermaine Clement and Taika Waititi who are executive producers on the series.

Total No. of seasons: 6

Total No: of season 6 episodes: 11

Total season 6 binge time: 4 hours and 50 minutes

Total series binge time: 24 hours and 42 minutes

This image released by Disney shows Quinta Brunson in a scene from Abbott Elementary. (Gilles Mingasson/Disney via AP)

“Abbott Elementary” (6 Emmy Nominations): Streaming on Hulu

If you ever wondered as a kid what went on in the teacher’s lounge at school, then “Abbott Elementary” is for you. The quirky, bighearted staff of a Philadelphia elementary school is followed by a documentary crew as they navigate underfunding, school board meetings and bus driver strikes, plus the fun stuff like field trips and class pets. It stars Quinta Brunson, who also created the show. Both Brunson and Sheryl Lee Ralph have won acting awards for the series.

Total No. of seasons: 4

Total No. of episodes in season 4: 22

Total season 4 binge time: 7 hours and 42 minutes

Total series binge time: 24 hours and 51 minutes

“Slow Horses” (5 Emmy Nominations): Streaming on Apple TV+

The British spy series stars Gary Oldman as Jackson Lamb, an eccentric, rude MI5 agent leading a group of spies called “slow horses” because they’ve made big mistakes on the job. It’s based on Mick Herron’s “Slough House” novels. The series didn’t catch the attention of Emmy voters until its third season but it’s got a near perfect rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

Total No. of seasons: 4

Total No. of season 4 episodes: 6

Total season 4 binge time: 4 hours and 34 minutes

Total series binge time: 18 hours and 25 minutes

“Paradise” (4 Emmy Nominations): Streaming on Hulu

Sterling K. Brown returned to TV in a dystopian series as a Secret Service agent protecting the president (played by James Marsden.) This president is not living at the White House or in Washington but a “Pleasantville”-like community. A mystery quickly presents itself with an unspooling of more questions after that.

Total No. of episodes: 8

Total binge time: 6 hours and 44 minutes

“Presumed Innocent” (4 Emmy Nominations): Streaming on Hulu

Real-life brother-in-laws Jake Gyllenhaal and Peter Sarsgaard star as adversaries in this TV adaptation of the Scott Turow novel. Gyllenhaal plays Chicago prosecutor Rusty Sabich, charged with murdering his colleague — an accusation that has fractured the district attorney’s office. Sarsgaard is attorney Tommy Molto, another co-worker intent on proving Sabich’s guilt. Meanwhile, Sabich’s marriage to Barbara (Ruth Negga) is falling apart under the weight of the accusation and the potential he could be found guilty.

Total No. of episodes: 8

Total viewing time: 5 hours and 55 minutes

“The Residence” (4 Emmy Nominations): Streaming on Netflix

Uzo Aduba stars as a quirky detective investigating a murder at the White House in this Netflix comedy. The series features a number of recognizable actors including Ken Marino, Randall Park, Susan Kelechi Watson, Jason Lee and Branson Pinchot in regular roles. The recurring cast includes Jane Curtin, Kylie Minogue and Al Frankin.

Total No. of episodes: 8

Total viewing time: 7 hours and 40 minutes

This image released by Netflix shows Kristen Bell, left, and Adam Brody in a scene from “Nobody Wants This.” (Stefania Rosini/Netflix via AP)

“Nobody Wants This” (3 Emmy nominations): Streaming on Netflix

Adam Brody and Kristen Bell co-star as a young rabbi and a podcaster with no religious affiliation who meet and begin dating in “Nobody Wants This” for Netflix. Is it smooth sailing from here? Not quite. The two must overcome their respective baggage, differences of religion and expectations from others.

Total No. of episodes: 10

Total binge time: 4 hours and 19 minutes

“Disclaimer” (2 Emmy Nominations): Streaming on Apple TV+

In “Disclaimer,” an acclaimed documentary filmmaker, played by Cate Blanchett, who has dedicated her career to uncovering truths is given a novel with a plot that sounds like a secret she’s been hiding for years. The series was written and directed by Oscar-winning director Alfonso Cuarón. It also stars Kevin Kline, Sacha Baron Cohen, Kodi Smit-McPhee, Lesley Manville and Louis Partridge.

Total No. of episodes: 7

Total binge time: 5 hours and 51 minutes

“The Diplomat” (2 Emmy Nominations): Streaming on Netflix

Keri Russell stars as Kate, a career diplomat assigned to be the U.S. ambassador to England. She wants to focus on foreign relations and policy but keeps getting pulled to do things like attend parties and give interviews to fashion magazines. Kate’s also got a rocky marriage to Hal (Rufus Sewell) who has also served as a diplomat and can’t seem to stay out of her way.

Total No. of seasons: 2

Total No. of season 2 episodes: 6

Total season 2 binge time: 4 hours and 53 minutes

Total series binge time: 11 hours and 36 minutes

“Poker Face” (2 Emmy Nominations): Streaming on Peacock

Natasha Lyonne stars as a woman with an uncanny ability to detect lies who each episode finds herself embroiled in a murder mystery. The show features recognizable guest stars like Adrien Brody, Cynthia Erivo, Nick Nolte, Tim Meadows, Katie Holmes, and John Mulaney. Its creator Rian Johnson is the writer and director of “Knives Out” and “Glass Onion.” He says the show is not a whodunit but a howdunit and it’s format is based on the case of the week shows he watched as a kid.

Total No. of episodes 22

Total No. of season 2 episodes: 12

Total season 2 binge time: 9 hours and 15 minutes

Total binge time: 18 hours and 20 minutes

“Somebody Somewhere” (2 Emmy Nomination): Streaming on Max

Bridget Everett and Jeff Hiller star in this comedy. Everett plays Sam, a single middle-aged woman living in Manhattan, Kansas, who when we first meet her, is grieving the death of her sister and distant from those around her. It’s like someone turns the lights on in her world when she befriends Joel (Jeff Hiller), a religious, gay man with a big heart who laughs at all of Sam’s jokes and loves her for who she is. Joel invites Sam to sing with his gay choir and she finds the acceptance and community she was looking for.

Total No. of episodes: 21

Total No. of season 3 episodes: 7

Total season 3 binge time: 3 hours and 22 minutes

Total binge time: 9 hours and 50 minutes

This image released by CBS shows Kathy Bates in a scene from “Matlock.” (Sonja Flemming/CBS via AP)

“Matlock” (1 Emmy Nomination): Streaming on Paramount+

Kathy Bates stars as Madeline Kingston, a wealthy lawyer who comes out of retirement under the alias Mattie Matlock. Mattie claims her reason for returning to work is that she needs money but, in reality, she’s out for revenge against the law firm.

Total No. of episodes: 19

Total binge time: 13 hours and 9 minutes

“Dope Thief” (1 Emmy Nomination): Streaming on Apple TV+

In “Dope Thief,” Brian Tyree Henry and Wagner Moura play longtime best friends who pose as DEA agents, conduct fake drug raids and steal stuff. It’s a great scam until they rob the wrong people.

Total No. of episodes: 8

Total binge time: 6 hours and 26 minutes

“The Four Seasons” (1 Emmy Nom

ination): Streaming on Netflix

A group of three middle-aged couples who’ve been best friends for years meet four times a year for a vacation. When one of the couples gets a divorce, their dynamic is thrown off. The series, co-created by Tina Fey, is based on a 1981 film written and directed by Alan Alda and stars Fey, Steve Carell, Colman Domingo and Will Forte.

Total No. of episodes: 8

Total binge time: 4 hours and 13 minutes

“The Handmaid’s Tale” (1 Emmy Nomination): Streaming on Hulu

“The Handmaid’s Tale” is based on Margaret Atwood’s novel in which the U.S. government has been overthrown by a patriarchal dictatorship called The Republic of Gilead. In Gilead, there’s a fertility crisis and women who can conceive are relegated as handmaids, who are baby makers for affluent families. Elisabeth Moss stars as June, a handmaid determined to resist this regime and reunite with her family. A sequel based adapted from Atwood’s “The Testaments” is in the works.

Total No. of episodes: 66

Total No. of season 6 episodes: 10

Total binge time for season 6: 7 hours and 49 minutes

Total binge time: 56 hours and 21 minutes

Lifestyle

Roman era mosaic panel with erotic theme that was stolen during World War II returns to Pompeii

POMPEII, Italy (AP) — A mosaic panel on travertine slabs, depicting an erotic theme from the Roman era, was returned to the archaeological park of Pompeii on Tuesday, after being stolen by a Nazi German captain during World War II.

The artwork was repatriated from Germany through diplomatic channels, arranged by the Italian Consulate in Stuttgart, Germany, after having been returned from the heirs of the last owner, a deceased German citizen.

The owner had received the mosaic as a gift from a Wehrmacht captain, assigned to the military supply chain in Italy during the war.

The mosaic — dating between mid- to last century B.C. and the first century — is considered a work of “extraordinary cultural interest,” experts said.

“It is the moment when the theme of domestic love becomes an artistic subject,” said Gabriel Zuchtriegel, director of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii and co-author of an essay dedicated to the returned work. “While the Hellenistic period, from the fourth to the first century B.C., exulted the passion of mythological and heroic figures, now we see a new theme.”

The heirs of the mosaic’s last owner in Germany contacted the Carabinieri unit in Rome that’s dedicated to protecting cultural heritage, which was in charge of the investigation, asking for information on how to return the mosaic to the Italian state. Authorities carried out the necessary checks to establish its authenticity and provenance, and then worked to repatriate the mosaic in September 2023.

The collaboration with the Archaeological Park of Pompeii was also key, as it made it possible to trace it to near the Mount Vesuvius volcano, despite the scarcity of data on the original context of its discovery, the Carabinieri said.

The panel was then assigned to the Archaeological Park of Pompeii where, suitably catalogued, it will be protected and available for educational and research purposes.

“Today’s return is like healing an open wound,” Zuchtriegel said, adding that the mosaic allows to reconstruct the story of that period, the first century A.D., before Pompeii was destroyed by the Vesuvius eruption in A.D. 79.

The park’s director also highlighted how the return by the heirs of its owner signals an important change in “mentality,” as “the sense of possession (of stolen art) becomes a heavy burden.”

“We see that often in the many letters we receive from people who may have stolen just a stone, to bring home a piece of Pompeii,” Zuchtriegel said.

He recalled the so-called “Pompeii curse,” which according to a popular superstition hits whoever steals artifacts in Pompeii.

The world-known legend suggests that those who steal finds from the ancient city of Pompeii will experience bad luck or misfortune. That has been fueled over the years by several tourists who return stolen items, claiming they brought them bad luck and caused tragic events.

Lifestyle

Nextdoor is partnering with local news providers

NEW YORK (AP) — Nextdoor, the social media site that aims to create connections among neighbors, is trying to shake off an uneven past and a nagging sense it is being underutilized. How? It is turning to professional journalists for help.

The company announced a partnership Tuesday with more than 3,500 local news providers who will regularly contribute material to the app. As part of a redesign, it is also expanding its ability to alert users about bad weather, power outages and other dangers, along with using AI to improve recommendations for restaurants, services and local points of interest.

“There should be enough value that we are creating for neighbors that they feel like they need to open up Nextdoor every single day,” said Nirav Tolia, the company’s co-founder and CEO. “And that isn’t the case today.”

The potential for Nextdoor to help itself and journalists at the same time is most intriguing.

Nextdoor is carrying portions of local news stories from providers in the area where the user lives. If people want to learn more, a link to the news site is included. At launch, Nextdoor says it has more than 50,000 news stories available, representing just over three-quarters of the app’s “neighborhoods.”

A future for news that never arrived

When Nextdoor began in 2011, the local news industry was in the early stages of a freefall that continues today. The number of journalists in the U.S. dropped from 40 per 100,000 residents in 2002 to slightly more than eight today, according to a study issued this month by Muck Rack and Rebuild Local News. Nearly a third of the nation’s counties have no full-time journalist.

Into this tumult came an app with a promising premise and infrastructure, perhaps a template for local news of the future. Its users — Nextdoor likes to call them “neighbors” — were organized into more than 200,000 distinct neighborhoods, with the ability to start conversations once shared over back fences: Do you know a reliable babysitter? What’s that building going up down the street? Who serves the best burger?

Yet Nextdoor’s developers knew technology, not the news business. They didn’t see a role for professional journalists at the outset.

“We thought in our early days that neighbors would take over, almost as citizen journalists or local reporters,” Tolia said. “I think we’ve come to the conclusion that neighbors can only do so much.”

Even worse, the site became a magnet for racists and cranks, the kind of neighbors you try to avoid. Nextdoor became so filled with suspicion — why is a person of a different color or nationality walking down the street? — that its moderators had to spend considerable time rooting out racist posts and changing rules to prevent them.

For some users, the negatives outweighed the positives.

“Nextdoor has been a valuable resource for my family,” Ralinda Harvey Smith, a woman from Santa Monica, Calif., wrote in the Los Angeles Times in 2020. “I found a nanny share for my kids on Nextdoor. When I posted looking for a mechanic to replace my car headlight, a neighbor offered to change it free of charge. When the pandemic struck and disinfectant wipes were impossible to come by, a woman on Nextdoor DM’d me offering to leave some on her porch.”

“Yet I’ve long seen remnants of racism across the site that have left me with a bad feeling not only about the app, but the city I love,” Smith wrote. That made her log on less frequently.

Trying to make Nextdoor essential for users

Whatever the reasons, enough users consider Nextdoor inessential that its leaders were compelled to make the changes being announced now. The site has 100 million registered users, but only about 25 million are on the site at least once a week, Tolia said. Nextdoor, which went public in 2021 to attract a new round of financing, wants to see them more often.

Nextdoor hired a former executive at The New York Times, Georg Petschnigg, as its chief design officer to oversee the changes.

The company said its surveys found users wanted to know more about what was going on in their communities beyond the utilitarian information. Other social networks are similarly bringing in more outside material, Tolia said. “When you rely on user-generated content, it’s kind of unpredictable in terms of quality, timeliness and relevance,” he said.

“If I were in their shoes, I’d be doing this. I don’t know why they didn’t do it sooner, but that’s for them to answer and not me,” said Chuck Todd, the former “Meet the Press” moderator who has taken an interest in local news since leaving NBC. Semafor this spring speculated Todd might be interested in buying Nextdoor. Todd wouldn’t discuss that.

He is waiting to see if Nextdoor has a real commitment to news or just to reaching more eyeballs.

“It’s an opportunity to do the one thing that Facebook could have done but chose not to,” Todd said. “You don’t want this to go down the road of just trying to get traffic for traffic’s sake, because that’s what happened to Facebook after it went public.”

The irony of engaging with professional journalists isn’t lost.

“It’s like what is old is new again,” said Sam Cholke, manager of distribution and audience growth for the Institute for Nonprofit News. Its hundreds of members include the Texas Tribune, the Plateau Daily News in Highlands, N.C., and the Daily Yonder in Whitesburg, Kentucky.

Several of its participating news organizations are joining with Nextdoor, and “my hope is that our members see significant benefits from it,” Cholke said.

Hoping for mutually beneficial relationship

The local news industry continues to suffer from the same problems that have led to its downfall the past two decades: a dwindling number of readers and advertisers. An offhand comment by Tolia — about how people used to pick up “a piece of dead tree” from their driveways to get their news — speaks to fading prospects.

Facebook’s deemphasis of news on its platform and Google’s increasing use of AI at the expense of referrals to news articles are adding to the death spiral, said Tim Franklin, head of the Medill Local News Initiative at Northwestern.

“If Nextdoor is another vessel to get readers to news sites, and local news sites in particular, it would come at a real moment of vulnerability for local news organizations and would be a real opportunity,” said Franklin, whose worry is that relying on third parties is unpredictable.

Josh Schneps, who runs a series of local news operations in New York City and Long Island, like the Flushing Times and Park Slope Courier, has already had material appear on Nextdoor in a soft launch and is seeing an increase in traffic to the sites.

“I feel like media is in a state of evolution and there’s no playbook,” Schneps said. “My goal is to get our content in front of as many people as possible. I’m more than happy to be the guinea pig” for Nextdoor, he said.

An industry — and a company — both need help. Maybe they can help each other.

___

David Bauder writes about the intersection of media and entertainment for the AP. Follow him at http://x.com/dbauder and https://bsky.app/profile/dbauder.bsky.social.

-

Europe5 days ago

Europe5 days agoWhat will happen now that Trump has turned on Putin?

-

Lifestyle5 days ago

Lifestyle5 days agoPhotos of Cuban women with long decorated nails

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoBill Ackman: Swift backlash after billionaire’s pro debut

-

Europe4 days ago

Europe4 days agoGerman tourist found alive 12 days after she was lost in the Australian Outback

-

Lifestyle4 days ago

Lifestyle4 days agoOne Tech Tip: All the ways to unsubscribe, after ‘click-to-cancel’ was blocked

-

Lifestyle5 days ago

Lifestyle5 days agoCuban women spend on extravagant nail art

-

Asia4 days ago

Asia4 days agoAir India crash: Engine fuel supply was cut just before Air India jet crash, preliminary report says

-

Lifestyle5 days ago

Lifestyle5 days agoSebeiba festival in Algeria carries on ancient tradition