Lifestyle

A South African artist hopes vibrant sculptures make parks more welcoming in a city known for danger

JOHANNESBURG (AP) — James Delaney wants his public art in South Africa’s biggest city to be more than a magnet for selfies and a delight for children. He’s determined to have the vibrant metal sculptures change the mood of its gritty and sometimes dangerous neighborhoods.

Over the past decade, Delaney has designed more than 100 sculptures for The Wilds Park in Johannesburg. A striking red steel kudu antelope stands near a hill’s summit. A curious assembly of stencil owls peer down from jacaranda trees. A life-size pink giraffe installation dominates a grassy clearing.

“Artworks can bring a sense of life to public spaces,” said Delaney, a 53-year-old sculptor and painter who has exhibited his work in London, Paris and New York.

“And public spaces need lots of people to be functional and to be safe.”

Authorities in Johannesburg have encouraged public art to improve safety and environmental conditions in the city of some 6 million people whose downtown has a reputation for crime and degradation. Johannesburg is considered one of the world’s most dangerous cities, based on crime data.

Much of Johannesburg’s street art and public works reflect South Africa’s former life under the white minority rule of apartheid and the efforts at reconciliation after that divisive system ended.

Delaney’s work strives to do something simpler for residents in a city where dirty, uninviting sidewalks and safety concerns make it rare for the average person to take a stroll.

“One can create a public space which is grass and trees and it’s OK and nice. But one has to do more than that to really attract people and to capture their imagination,” Delaney said.

The Wilds is in the midst of Johannesburg’s contrasts.

One side of the park is bordered by the tree-lined Killarney suburb and affluent Houghton, home to Nelson Mandela during the final years of his presidency as the country’s first Black leader. The other side borders a transition into the bustling, sometimes broken-down areas of Berea and Yeoville.

Lydia Ndhlovu, a 38-year-old mother, watched her children play on the jungle gym, a break from their apartment with no yard.

“I don’t feel safe being alone here with them, but I like seeing the elderly people enjoying the park from my window, because then I know we can be free and also come,” she said.

Some residents say Johannesburg’s reputation for crime is unfair.

“Quite often the narrative in the city of Johannesburg is all parks are unsafe,” said Jenny Moodley, a spokeswoman for Johannesburg City Parks, which maintains 22 nature reserves, 15 bird sanctuaries and more than 2,000 public parks.

“Many of these open spaces are safe, little children play unsupervised, and we know elements such as art reinforce that this is a vibrant space to play, to come together with your families and friends and to also express yourself,” Moodley said.

Delaney first encountered The Wilds as an overgrown, deserted park while walking his puppy Pablo — named after Picasso — in 2014. Since then, he has repaired and painted benches, pruned plants and attracted volunteers and donors to help turn it into a buzzing meeting point.

The special ingredient might be the sculptures that now draw moms with babies, yoga enthusiasts and schoolchildren from nearby apartment blocks.

Delaney last week unveiled a second urban park regeneration in Killarney, where a 3-meter-high (9.8-foot) bright orange gate features a sculpture of a raptor perched on a native aloe plant, encouraging passers-by to enter and explore.

Anna Starcke, an 88-year-old former political analyst and journalist, is one of Killarney’s oldest residents, though her pink lipstick and green sunglasses strike a more contemporary tone. To her, the art in the parks speaks of inclusion. One of the delights of her day is chatting with other visitors.

“It’s very important that people get the feeling that it’s theirs because that is the big thing, that Black people (during apartheid) never felt it’s theirs,” she said. “If we can get a majority of people to care about their parks, art in their parks, and being together in their parks, sitting on the same bench, then we have won.”

___

AP Africa news: https://apnews.com/hub/africa

Lifestyle

‘The Salt Path:’ A book that captured the hearts of millions, but now mired in controversy

LONDON (AP) — “The Salt Path” is a memoir of resilience and courage that captured the hearts of millions and which was subsequently adapted for the big screen, with actors Gillian Anderson and Jason Isaacs taking the lead roles.

But now, the book and the film are mired in a controversy that could see them suffer that very modern phenomenon — being canceled.

A bombshell report in last Sunday’s “The Observer” newspaper in the U.K. claimed there was more to the 2018 book than met the eye — that key elements of the story had been fabricated.

Author Raynor Winn stands accused of betraying the trust of her readers and of reaping a windfall on the back of lies. Winn accepts “mistakes” were made, but that the overarching allegations were “highly misleading.” She has sought legal counsel.

On Friday, publisher Penguin Michael Joseph agreed with Winn to delay the publication of her next book, according to specialist magazine The Bookseller.

The book

Winn’s book tells how she and her husband of 32 years, Moth Winn — a well-to-do couple — made the impulsive decision to walk the rugged 630 miles (around 1,000 kilometers) of the South West Coast Path in the southwest of England after losing their house because of a bad business investment.

Broke and homeless, the memoir relays how the couple achieved spiritual renewal during their trek, which lasted several months and which saw them carry essentials and a tent on their back.

The book also recounts how Moth Winn was diagnosed with the extremely rare and incurable neurological condition, corticobasal degeneration, or CBD, and how his symptoms had abated following the walk.

It sold 2 million copies in the U.K., became a regular read at book clubs, spawned two sequels and the film adaptation, which was released this spring, to generally positive reviews.

On its website, publisher Penguin described the book as “an unflinchingly honest, inspiring and life-affirming true story of coming to terms with grief and the healing power of the natural world. Ultimately, it is a portrayal of home, and how it can be lost, rebuilt, and rediscovered in the most unexpected ways.”

That statement was released before the controversy that erupted last Sunday.

The controversy

In a wide-ranging investigation, The Observer said that it found a series of fabrications in Raynor Winn’s tale. It said the couple’s legal names are Sally and Timothy Walker, and that Winn misrepresented the events that led to the couple losing their home.

The newspaper said that the couple lost their home following accusations that Winn had stolen tens of thousands of pounds from her employer. It also said that the couple had owned a house in France since 2007, meaning that they weren’t homeless.

And perhaps more damaging, the newspaper said that it had spoken to medical experts who were skeptical about Moth having CBD, given his lack of acute symptoms and his apparent ability to reverse them.

The book’s ability to engender empathy from its readers relied on their personal circumstances. Without those hooks, it’s a very different tale.

The response

As a writer of what was represented as a true story, Winn had to attest to her publisher that the book was a fair and honest reflection of what transpired.

Any memoir may have omissions or hazy recollections.

But making things up are a clear no-no.

In the immediate aftermath, Winn made a brief comment on her website about the “highly misleading” accusations and insisted that the book “lays bare the physical and spiritual journey Moth and I shared, an experience that transformed us completely and altered the course of our lives. This is the true story of our journey.”

She fleshed out her response on Wednesday, describing the previous few days have been “some of the hardest of my life,” while acknowledging “mistakes” in her business career.

She also linked documents appearing to show Moth had been diagnosed with CBD, and described how the accusations that Moth made up his illness have left them “devastated.”

After the allegations were published, Penguin said it undertook “the necessary pre-publication due diligence,” and that prior to the Observer story, it hadn’t received any concerns about the book’s content.

The long-term

It’ll be interesting to see how the book’s sales and the film’s box office receipts are affected by the controversy. Those should start emerging in the coming days.

In addition, there are questions now as to whether the film will find a U.S. distributor and whether Winn, in particular, will face compensation claims, potentially even from readers.

Winn was meant to be in the western England town of Shrewsbury on Friday on the Saltlines tour, a “words and music collaboration” between her and folk band The Gigspanner Big Band.

Her legal team said that Winn is “deeply sorry to let down those who were planning to attend the Saltlines tour, but while this process is ongoing, she will be unable to take part.”

Lifestyle

Sebeiba festival in Algeria carries on ancient tradition

DJANET, Algeria (AP) — In one hand, the dancers hold swords symbolizing battle. In the other, a piece of cloth symbolizing peace. They dance a shuffling “step-step” to the beat of drums and chanting from the women encircling them, all adorned in their finest traditional garments and jewelry.

They’re performing the rituals of the 3,000-year-old annual Sebeiba festival of Djanet, a southeastern Algerian oasis town deep in the Sahara, just over 200 kilometers (about 125 miles) from the Libyan border.

Sebeiba is a core tradition of the Tuareg people, native to the Sahara and parts of West Africa. The Tuareg are Muslim, and their native language is Tamasheq, though many speak some combination of French, Modern Standard Arabic, Algerian Arabic (Darija) and English.

The festival lasts 10 days, and ends with a daylong dance competition between two neighborhoods in Djanet — Zelouaz, or Tsagit, and El Mihan, or Taghorfit. The winner is decided by judges from a third neighborhood, Adjahil, by selecting the group with the most beautiful costumes, dances, jewelry, poetry and songs.

Significance of the festival

The Tuaregs in Djanet say there are two legends explaining the significance of Sebeiba, though oral traditions vary. The first says the festival was put on to celebrate peace and joy after Moses defeated the Pharaoh in the Exodus story.

“In commemoration of this great historical event, when God saved Moses and his people from the tyranny of the oppressive Pharaoh, the people of Djanet came out and celebrated through dance,” said Ahmed Benhaoued, a Tuareg guide at his family’s tourism agency, Admer Voyages. He has lived in Djanet all his life.

The second legend says the festival commemorates the resolution of a historic rivalry between Zelouaz and El Mihan.

“The festival is a proud tradition of the Tuareg in Djanet,” Benhaoued said. “Some call it ‘the Sebeiba celebration,’ or ‘the war dance without bloodshed’ or ‘the dance of peace.’”

Today, Sebeiba is also a point of cultural pride. Recognized by UNESCO since 2014 as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, Sebeiba coincides with Ashoura, a day marking the 10th day of Muharram, or the first month of the Islamic year. Some in Djanet fast for up to three days before Sebeiba.

This year, Ashoura and Sebeiba fell on July 6, when temperatures in Djanet reached about 38 C (100 F). Still, more than 1,000 people gathered to watch Sebeiba at a sandy square marking the center point between the two neighborhoods, where the festival is held each year.

Each group starts at one end of the square — Zelouaz to the north and El Mihan to the south.

The dancers are young men from the neighborhoods dressed in dark robes accented by bright yellow, red and blue accessories and tall, maroon hats called Tkoumbout adorned with silver jewelry.

The men’s dances and women’s chants have been passed down through generations. Children participate in the festivities by mimicking the older performers. Boys brandish miniature swords and scarves in their small hands and girls stand with the female drummers.

A friendly dance competition

This year, El Mihan won the dance competition. But Cheikh Hassani, director of Indigenous Institutional Dance of Sebeiba, emphasized that despite the naming of a winner, the festival remains a friendly celebration — meant above all to honor their ancestors in a spirit of unity.

“Sebeiba is not just a dance,” Hassani said. “People used to think you just come, you dance — no, it represents so much more. For the people of Djanet, it’s a sort of sacred day.”

While the most widely known part of Sebeiba is the dance competition on the last day, the nine days leading up to it are also full of celebration. Tuareg from Libya and from other cities in the Algerian Sahara come to gatherings each night, when the temperature has cooled, to watch the performers rehearse.

Hassani said the generational inheritance of the festival’s customs helps them keep the spirits of their ancestors alive.

“We can’t let it go,” he said. “This is our heritage, and today it’s become a heritage of all humanity, an international heritage.”

According to legend, Benhaoued said, there will be winds and storms if Sebeiba is not held.

“It is said that this actually happened once when the festival was not held, so a woman went out into the streets with her drum, beating it until the storm calmed down,” the Tuareg guide added.

About 50 foreign tourists joined the people of Djanet for the final dance competition, hailing mostly from European countries such as France, Poland and Germany. Several also came from the neighboring countries of Libya and Niger.

Djanet is one of many Algerian cities experiencing an increase in tourism over the past two years thanks to government efforts to boost the number of foreign visitors, especially to scenic sites like the Sahara which makes up 83% of the North African country’s surface area.

The government introduced a new visa-on-arrival program in January 2023 for all nonexempt foreign tourists traveling to the Sahara. Additionally, the national airline, Air Algerie, launched a flight between Paris and Djanet in December 2024 during the winter season, when tourists from across the world travel to Djanet for camping excursions deep into the Sahara.

“The Sebeiba isn’t just something for the people of Djanet,” Hassani said. “We have the honor of preserving this heritage of humanity. That’s an honor for us.”

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

Lifestyle

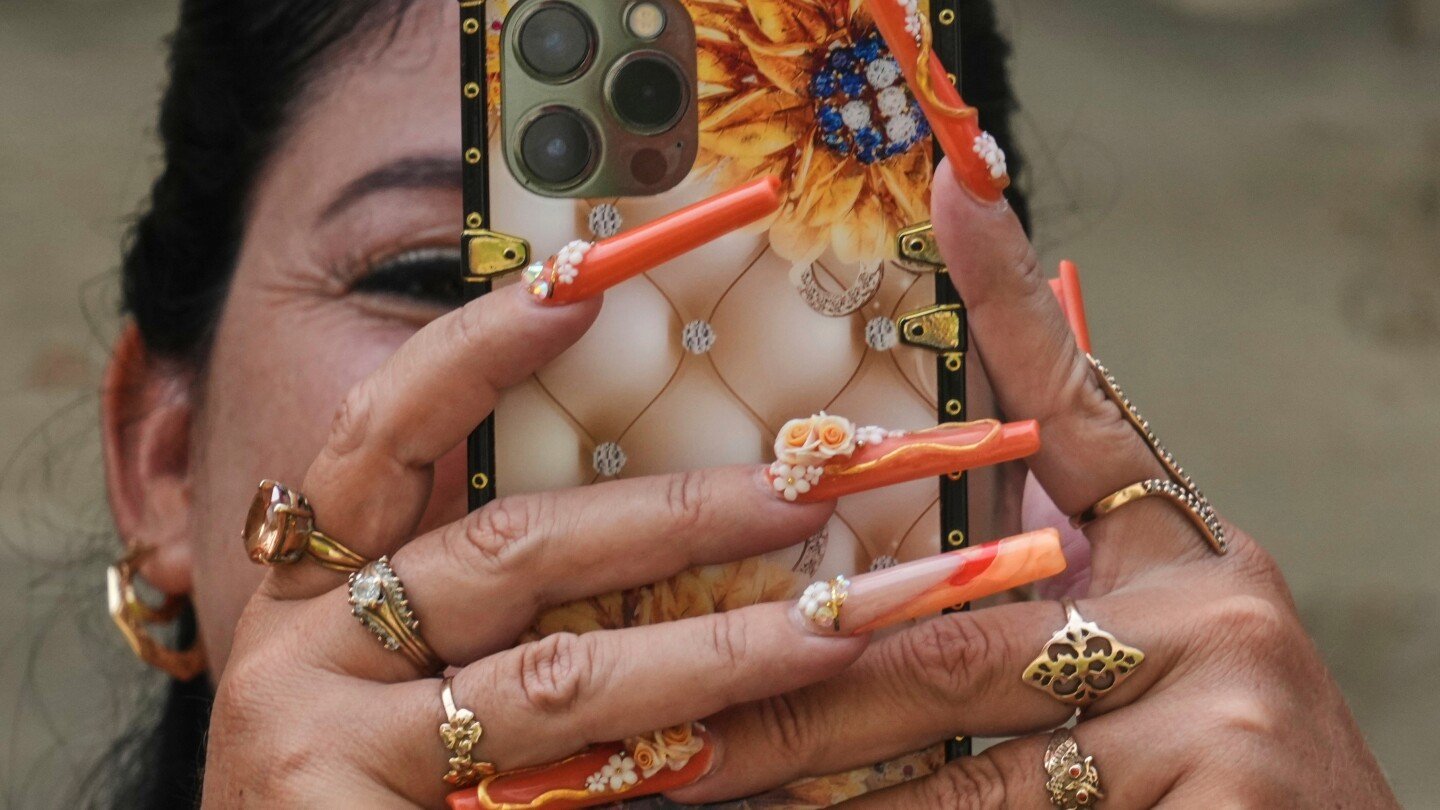

Photos of Cuban women with long decorated nails

HAVANA (AP) — Despite Cuba’s economic crisis, many women are embracing elaborate nail art as a bold fashion statement. Manicurists like Marisel Darias Valdés treat it as an art form, creating intricate designs that can take hours and cost up to $40 — more than triple the average monthly salary.

___

This is a photo gallery curated by AP photo editors.

Manicurist Dayana Roche works on a client’s nails at her home-run nail salon in Havana, Cuba, Thursday, June 26, 2025. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

Yalema Gonzalez, sporting long decorated nails, collects her sun-dried laundry from a clothesline, in La Gallega, Havana province, Cuba, Saturday, June 28, 2025. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

Mariam Camila Sosa strikes a pose to show off her freshly decorated fingernails, at a home-run nail salon in Havana, Cuba, Tuesday, June 24, 2025. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

Maite Hernandez gets into a taxi to go home after having her nails done at a home-run salon in Havana, Cuba, Saturday, July 5, 2025. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

A manicurist works on a client’s nails as others wait at a home-run nail salon in Havana, Cuba, Monday, July 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

Manicurist Marisel Darias Valdes works on a client’s nails in Havana, Cuba, Tuesday, June 24, 2025. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

Manicurist Marisel Darias Valdes works on a client’s nails at a salon she has set up in her home, in Havana, Cuba, Tuesday, June 24, 2025. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

Mariam Camila Sosa places her hand under a UV lamp to speed dry her manicured nails at a home-run nail salon, in Havana, Cuba, Tuesday, June 24, 2025. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

Yalema Gonzalez, wearing long, decorative nails, drinks her afternoon coffee at her home in La Gallega, Havana province, Cuba, Saturday, June 28, 2025. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

Maite Hernandez, donning long, decorated nails, takes her change from a vegetable vendor, in Havana, Cuba, Saturday, July 5, 2025. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

Maite Hernandez takes a taxi home after having her nails done at a home-run nail salon in Havana, Cuba, Saturday, July 5, 2025. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa)

-

Asia4 days ago

Asia4 days agoIndonesia’s Mount Lewotobi Laki Laki erupts sending ash 11 miles into sky

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoTyrese Haliburton to miss entire 2025-26 NBA season to rehab torn Achilles tendon

-

Europe2 days ago

Europe2 days agoExtreme heat is a killer. A recent heat wave shows how much more deadly its becoming as humans warm the world

-

Africa3 days ago

Africa3 days agoCairo telecom fire injures 14, disrupts internet nationwide

-

Europe3 days ago

Europe3 days agoHe was born to a US citizen soldier on an army base in Germany. Now he’s been deported to Jamaica, a country he’d never been to

-

Asia3 days ago

Asia3 days agoA torpedoed US Navy ship escaped the Pacific in reverse, using coconut logs. Its sunken bow has just been found

-

Europe2 days ago

Europe2 days agoTrump promised 200 deals by now. He’s gotten 3, and 1 more is getting very close

-

Africa4 days ago

Africa4 days agoKenya: at least 10 dead in ongoing protests, 29 injured nationwide