Africa

U.S. Secretary Rubio oversees Congo-Rwanda deal to ease mineral conflict

Secretary of State Marco Rubio on Friday oversaw the signing by Congo and Rwanda of a pledge to work toward a peace deal that would ease U.S. access to critical minerals in resource-rich eastern Congo, bringing U.S. influence to bear in a minerals trade that has helped fuel conflict that has killed millions for three decades.

Rubio’s participation in the Washington ceremony with his Central African counterparts is an early step in what the Trump administration says is a rebuilding of U.S. foreign policy to focus on transactions of direct financial or strategic benefit to the United States.

Congo and Rwanda hope the involvement of the United States — and the incentive of major investment if there’s enough security for U.S. companies to work safely in east Congo — will calm the fighting and militia violence that have defied peacekeeping and negotiation since the mid-1990s.

The risk is that the United States becomes involved in or worsens the militia violence, corruption, exploitation and rights abuses surrounding the mining and trade of east Congo’s riches.

“A durable peace … will open the door for greater U.S. and broader Western investment, which will bring about economic opportunities and prosperity,” Rubio said, adding that it would “advance President Trump’s prosperity agenda for the world.”

Congo is the world’s largest producer of cobalt, a mineral used to make lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles and smartphones. It also has substantial gold, diamond and copper reserves.

Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi has sought out a deal with the Trump administration that could offer the U.S. better access to his country’s resources in exchange for U.S. help calming hostilities.

Eastern Congo has been in and out of crisis for decades with more than 100 armed groups, most of which are vying for territory in the mining region near the border with Rwanda. The conflict has created one of the world’s largest humanitarian disasters with more than 7 million people displaced, including 100,000 who fled homes this year.

Conflict in eastern Congo is estimated to have killed 6 million people since the mid-1990s, in the wake of the Rwanda genocide. Some of the ethnic Hutu extremists responsible for the 1994 killing of an estimated 1 million of Rwanda’s minority ethnic Tutsis and Hutu moderates later fled across the border into eastern Congo, fueling the proxy fighting between rival militias aligned to the two governments.

“Today marks not an end but a beginning,” Congolese Foreign Minister Therese Kayikwamba Wagner said Friday before signing the broad agreement, which commits Rwanda and Congo to draft a peace accord and work to instill security and a good business environment, allow the return of the millions of displaced and accomplish other goals.

“The good news is there is hope for peace,” she said. “The real news is peace must be earned.”

She directed part of her remarks to the civilians of east Congo, brutalized, isolated and displaced by the fighting: “We know you are watching this moment with concern, with hope and, yes, with doubt. You are entitled to actions that measure up to the suffering you have endured.”

Rwandan Foreign Minister Olivier Nduhungirehe said the two rival governments were now addressing the root causes of the hostility between them, the most important of which he said were security and the ability of refugees to return home.

“Very importantly, we are discussing how to build new regional economic value chains that link our countries, including with American private sector investment,” he said.

Trump’s senior adviser for Africa, Massad Boulos, the father-in-law of Trump’s daughter Tiffany, helped broker the U.S. role in promoting security in east Congo, part of an opening that Boulos has said could involve multibillion-dollar investments.

The response from Congolese civil society Friday mixed hope with skepticism.

Rights advocate Christophe Muisa in Goma, a city in east Congo that the powerful, Rwandan-backed M23 armed group seized earlier this year, said the U.S. is the main beneficiary of the deal. He urged his government not to “subcontract its security.”

Georges Kapiamba, the president of the Congolese Association for the Access to Justice, a nongovernmental organization focusing on rights, justice and addressing corruption, said he supported a mineral-and-security deal with the U.S., but worried his own government could blow it by siphoning off the proceeds.

Three months into Trump’s second term, his administration and Republican lawmakers have made good on pledges to pare U.S. diplomacy and foreign assistance down to agreements that most directly serve their perception of U.S. strategic and financial interests. The administration has terminated thousands of U.S. aid and development workers and programs that worked more broadly for global development.

In another such transactional deal, the Trump administration is negotiating with Ukraine over a minerals deal that the U.S. is demanding as repayment for past U.S. military support after Russia invaded in 2022.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy initially proposed that deal last fall in hopes of strengthening his country’s hand in its conflict with Russia by tying U.S. interests to Ukraine’s future.

If the deal the U.S. is envisioning in east Congo goes well, it might end up stabilizing the region, said Gyude Moore, a former Cabinet minister in the West African nation of Liberia, now at the Center for Global Development, a think tank in Washington.

If not, “this deal, especially in a region crawling with conflict where there hasn’t been a credible political solution, is fraught with risks for the United States as it pursues this extractive foreign policy in Africa,” Moore said.

Liam Karr, the Africa team lead at the Washington-based American Enterprise Institute’s critical threats project, said the Trump administration and its advisers know enough to avoid the risks, including those of getting American security forces directly involved.

The larger risk is that American intervention meets the fate of U.N. and African peace efforts before it, Karr said. “And this just kind of falls flat on its face, and doesn’t go anywhere.”

Africa

Ramaphosa suspends police minister amid corruption allegations

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa has suspended Police Minister Senzo Mchunu following serious allegations made by General Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi, a top police official. Mkhwanazi accused Mchunu and Deputy Police Commissioner Shadrack Sibiya of interfering in sensitive investigations and colluding with criminal syndicates.

The suspension comes amid growing concern over alleged political interference within key law enforcement agencies. President Ramaphosa announced the decision publicly, stating, “In order for the Commission to execute its functions effectively, I have decided to put the Minister of Police Mr Senzo Mchunu on a leave of absence with immediate effect. The Minister has undertaken to give his full cooperation to the Commission to enable it to work properly.”

Ramaphosa has appointed Professor Firoz Cachalia as acting Minister of Police. Meanwhile, Mkhwanazi further alleged that Mchunu and Sibiya disbanded a critical crime-fighting unit that was investigating a string of politically motivated killings. These killings were reportedly linked to organized criminal networks.

The President also outlined the scope of the inquiry. “The Commission will investigate the role of current or former senior officials in certain institutions who may have aided or abetted the alleged criminal activity; or failed to act on credible intelligence or internal warnings; or benefited financially or politically from a syndicate’s operations,” Ramaphosa said.

Opposition parties have criticized the President for not taking stronger action. They argue that placing Mchunu on leave falls short of accountability and have called for his immediate dismissal instead.

Africa

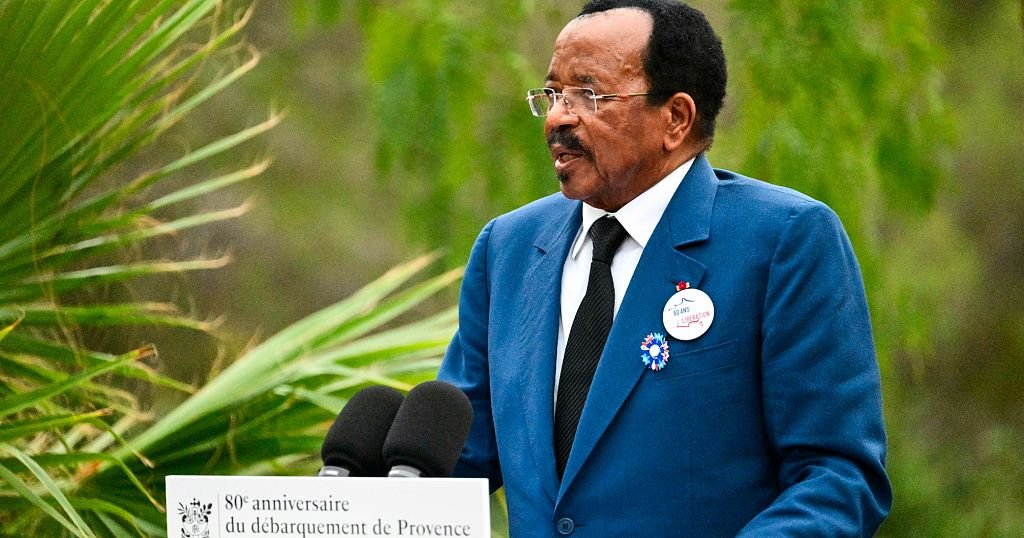

Cameroon’s Paul Biya, 92, announces bid for another term

Cameroon’s longtime leader, President Paul Biya, has officially announced he will run for another term in office, ending months of speculation over his political future. The 92-year-old made the announcement on social media, stating his continued determination to serve and promising that “the best is yet to come.”

Biya has been at the helm of Cameroon for over 40 years, making him the second longest-serving president in Africa. His decision to seek re-election has sparked criticism from opposition figures and human rights advocates. One prominent activist described the announcement as a clear sign of Cameroon’s stalled political transition, adding that the country is in urgent need of democratic change and accountable leadership.

In 2018, Biya secured a controversial victory with over 70 percent of the vote. That election was marked by allegations of fraud, low voter turnout, and violence.

The country’s conflict-ridden English-speaking regions have been deeply affected by a separatist crisis that has forced thousands of students out of school and led to deadly clashes between security forces and armed groups.

Throughout his presidency, Biya has faced accusations of corruption and failure to address national grievances. His frequent absences from the country for medical treatment have also raised concerns about his health and ability to govern effectively.

As the country heads toward another election cycle, Biya’s bid for another term promises to be a polarizing chapter in Cameroon’s already complex political landscape.

Africa

Nigerian ex-president Buhari dies at 82 in London

Muhammadu Buhari died Sunday in London, where he had been receiving medical treatment.

He first took power in Africa’s most populous nation in 1983, after a military coup, running an authoritarian regime until fellow soldiers ousted him less than 20 months later. When he was elected in 2015 on his fourth attempt, he became the first opposition candidate to win a presidential election there.

Buhari rode into power in that election on a wave of goodwill after promising to rid Nigeria of chronic corruption and a deadly security crisis. He led until 2023, during a period marked by Boko Haram’s extremist violence in the northeast and a plunging economy.

Current President Bola Tinubu in a statement described Buhari as “a patriot, a soldier, a statesman … to the very core.” Tinubu dispatched the vice president to bring Buhari’s body home from London.

Others across Nigeria remembered Buhari as a president who left the country of more than 200 million people — divided between a largely Muslim north and Christian south — more at odds than before.

“The uneven response to Buhari’s death, with muted disillusionment in some quarters and sadness in others, is a reflection of how difficult it is to unite a country and his inability to do so after decades in the public eye,” said Afolabi Adekaiyaoja, an Abuja-based political scientist.

Coming from Nigeria’s north, the lanky, austere Buhari had vowed to end extremist killings and clean up rampant corruption in one of Africa’s largest economies and oil producers.

By the end of his eight-year tenure, however, goodwill toward him had faded into discontent. Insecurity had only grown, and corruption was more widespread.

Nigeria also fell into a recession amid slumping global oil prices and attacks by militants in the sprawling oil-rich Niger Delta region. The currency faltered as Buhari pursued unorthodox monetary policies to defend its fixed price to the dollar, and a massive foreign currency shortage worsened. Inflation was in the double digits.

Civil society accused him of authoritarian tendencies after protesters were killed during a protest against police brutality and over his decision to restrict access to social media, as young people vented their frustrations against economic and security problems.

Buhari’s attempts at managing the problems were complicated by prolonged medical stays abroad. His absences, with few details, created anxiety among Nigerians and some calls for him to be replaced. There also was anger over his seeking taxpayer-funded health care abroad while millions suffered from poor health facilities at home.

“I need a longer time to rest,” the president once said in a rare comment during his time away.

His presidency saw a rare bright moment in Nigeria’s fight against Boko Haram — the safe return of dozens of Chibok schoolgirls seized in a mass abduction in 2014 that drew global attention.

But others among the thousands of people abducted by Boko Haram over the years remain missing — a powerful symbol of the government’s failure to protect civilians.

At the end of 2016, Buhari announced that the extremist group had been crushed, driven by the military from its remote strongholds.

“The terrorists are on the run, and no longer have a place to hide,” he boasted.

But suicide bombings and other attacks remained a threat, and the military’s fight against Boko Haram continued to be hurt by allegations of abuses by troops against civilians. In early 2017, the accidental military bombing of a displaced persons camp in the northeast killed more than 100 people, including aid workers. The U.N. refugee chief called the killings “truly catastrophic.”

As Nigeria’s military reclaimed more area from Boko Haram’s control, a vast humanitarian crisis was revealed. Aid groups began alerting the world to people dying from malnutrition, even as government officials denied the crisis and accused aid groups of exaggerating the situation to attract donations.

The extremist threat and humanitarian crisis in the northeast — now exacerbated by Trump administration aid cuts — continues today.

Years earlier, as Nigeria’s military ruler, Buhari oversaw a regime that executed drug dealers, returned looted state assets and sent soldiers to the streets with whips to enforce traffic laws. With oil prices slumping and Nigerians saying foreigners were depriving them of work, the regime also ordered an estimated 700,000 illegal immigrants to leave the country.

Meanwhile, government workers arriving late to their offices were forced to perform squats in a “war against indiscipline” that won many followers. Buhari’s administration, however, was also criticized by rights groups and others for detaining journalists critical of the government and for passing laws that allowed indefinite detention without trial.

As he pursued the presidency decades later, Buhari said he had undergone radical changes and that he now championed democracy. But some of his past stances haunted him, including statements in the 1980s that he would introduce Islamic law across Nigeria.

-

Europe5 days ago

Europe5 days agoBondi and Hegseth might be messing up — but they’re doing what Trump picked them to do

-

Africa5 days ago

Africa5 days agoGreece blocks asylum claims after surge in migrant arrivals

-

Lifestyle3 days ago

Lifestyle3 days agoOne Tech Tip: All the ways to unsubscribe, after ‘click-to-cancel’ was blocked

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoBill Ackman: Swift backlash after billionaire’s pro debut

-

Asia5 days ago

Asia5 days agoSouth Korea’s former President Yoon Suk Yeol back in custody over insurrection probe

-

Europe3 days ago

Europe3 days agoAs South Korea becomes a key arms supplier to US allies, its best customer is on the edge of a warzone

-

Asia3 days ago

Asia3 days agoA Trump tariff letter is the best news this Southeast Asian junta has had in a while

-

Lifestyle4 days ago

Lifestyle4 days agoHealthy workday snacks include a smart mix of energy-boosters