CNN

—

In a quiet corner of Glasgow’s East End, a radical public health experiment is underway. For the first time in the United Kingdom, people who inject illicit drugs such as heroin and cocaine can do so under medical supervision – in a safe environment and indoors.

No arrests. No judgment. No questions about where the drugs came from – only how to make their use less deadly.

The facility, known as the Thistle, opened in January amid mounting political and public health pressure to confront Scotland’s deepening drug crisis. With the highest rate of drug-related deaths in Europe, Scottish health officials say, there have long been calls for a more pragmatic, compassionate response.

Funded by the devolved Scottish government and modelled on more than 100 similar sites across Europe and North America, the pilot safe drug consumption facility marks a significant departure from the UK’s traditionally punitive approach to illegal drug use.

Dorothy Bain, who heads Scotland’s prosecution service and advises the government, told a UK parliamentary committee in May that “it would not be in the public interest to prosecute users of the Glasgow safer drug consumption facility for possession of drugs for personal use.”

She added that the approach would be kept under review to ensure it “is not causing difficulties, raising the risk of further criminality or having an unlawful impact on the community.”

Supporters describe it as a long-overdue shift toward harm reduction. Critics warn it risks becoming a place where damaging addiction is maintained, not treated.

Located in a low-slung clinical building near the city center, the Thistle is a space where individuals bring their own drugs, prepare them on site, and inject under the watchful eyes of trained staff.

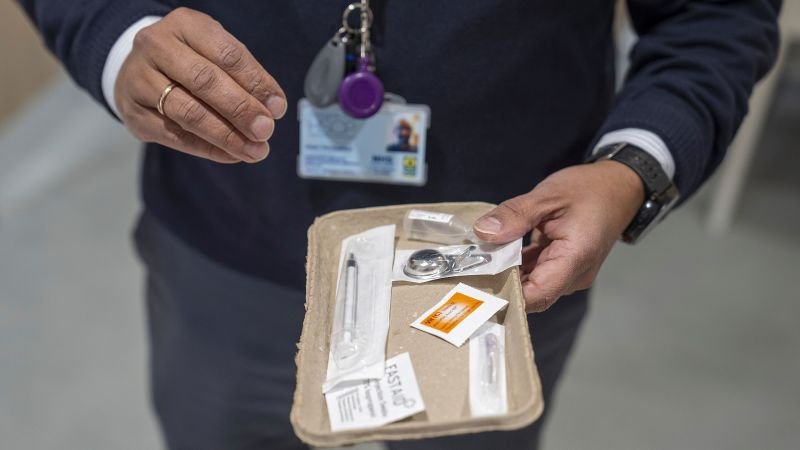

The service provides no substances, nor does it allow drug sharing between users. What it offers instead is clean equipment, medical oversight, and a protected environment for a population who might otherwise use in alleyways, public toilets or dumpster sheds, with the associated risks for themselves and the wider community.

“We’ve had almost 2,500 injections inside the facility,” Dr. Saket Priyadarshi, the clinical lead of the Thistle, told a CNN team who visited the facility in early June. “That’s 2,500 less injections in the community, in parks, alleyways, car parks.”

Dr. Saket Priyadarshi tells CNN about types of drug use at the Thistle

Dr. Saket Priyadarshi tells CNN about types of drug use at the Thistle

00:27

All users must register before receiving support, providing only their initials and date of birth. Staff ask what drugs they plan to use and how. Then, they observe – not intervene – ready to act in the event of an emergency.

“We’ve had to manage over 30 medical emergencies inside the facility,” Priyadarshi said. “Some of them were severe overdoses that most likely would have ended in fatalities if we hadn’t been able to respond to them immediately here.”

Nurses work with patients to reduce harm wherever possible, advising on injection technique, equipment, and vein placement.

“We’ll spend a bit of time with them. Just (to) try and get the vein finder working,” said Lynn MacDonald, the service manager at the facility, referring to a handheld device that uses infrared light to illuminate veins beneath the skin.

“People have often learnt technique from other people who are using it and it’s not particularly good,” she told CNN. With equipment such as vein finders, she said, the staff at the Thistle are able to highlight “better” sites of injection to “reduce harm and make the injection safer.”

The Scottish government told CNN that the service has already delivered results in terms of public health.

“Through the ability of staff to respond quickly in the event of an overdose, the Thistle service has already saved lives,” Scottish health secretary Neil Gray said. The service, he said, is “helping to protect people against blood-borne viruses and taking used needles off the street.”

The Thistle bears little resemblance to a medical clinic. There are no fluorescent white lights, no clinical uniforms, and no sterile white rooms. Even the language has been reimagined: users aren’t brought into “interview rooms,” but welcomed into “chat rooms.”

The space itself is soft and deliberate, – furnished with books, jigsaws, warm lighting and a café-style area where people can sit, drink tea, shower, or have their clothes washed.

“The whole service is just designed to that ethos of treating people with a bit of dignity, a bit of respect, bringing them in, making them feel welcome,” Macdonald told CNN. “We want them to leave knowing somebody cares about them and we’re looking forward to seeing them safe and well again.”

For Margaret Montgomery, whose son Mark began using heroin at 17, the existence of the Thistle offers a degree of solace that once felt impossible.

Now in his fifties, Mark is no longer using – but it took years, and distance, to get there.

“My son went into treatment and it’s like six weeks, three months, six months. That’s not enough time. There’s no aftercare,” Montgomery told CNN.

She added that she’d asked her son whether he would have used the Thistle “all those years ago.”

“He said, ‘yes, I probably would have used it because of the other facilities that they’re offering in there.’” Mark declined to speak with CNN himself but was happy for his mother to recount his experience.

What the Thistle represents, for Montgomery, is not approval – but reprieve. “Nobody wants to think their children are taking drugs anywhere,” she said. “There must be parents that are sat out there and they’re going, ‘well thank god he’s going in there and he’s doing that in there, not in a bin shed.’”

Her support is unflinching – and practical. She is the chairperson of a family support group that was consulted about the Thistle.

“I think the Thistle’s the best thing that’s happened in Glasgow,” she told CNN.

‘Ethical and moral question’

Others see the facility not as an act of compassion, but as a quiet surrender.

Annemarie Ward, who has been in recovery for 27 years, believes that without a clear route to abstinence, harm reduction risks becoming a form of institutionalized maintenance.

“Have we given up trying to help people? Are we just trying to maintain people’s addictions now?” she told CNN.

Ward, who is from Glasgow, is the chief executive of the charity Faces and Voices of Recovery UK (Favor UK), and a campaigning voice for better access and treatment choices for those seeking help with addiction.

For Ward, the danger lies not in what the Thistle does, but in what it omits: a vision of freedom from dependency. Without that, she argues, the ethics of such facilities become blurred.

“If our whole system is focused on maintaining people’s addiction and not giving them the opportunity to exit that system,” she said, “I think there’s an ethical and moral question that we need to ask.”

The Thistle is “just prolonging the agony of addiction,” she said. “If you know anybody who’s suffered in that way or loved anybody that’s suffered that way you would see how inhumane this actually is.”

But Glasgow City Council says that the facility is one strand of a broader strategy.

The council says that the Thistle does not divert “from other essential alcohol and drug services in the city,” adding that the local authority “also invests heavily in treatment and care and recovery services.”

“Comparing these interventions is not helpful,” the council said in a statement. “All services are equally important – and needed – to allow us to support people who most need them.”

The idea itself is not new.

The world’s first safer drug consumption room opened in Switzerland in 1986 -– a clinical counterpoint to street-level chaos. Since then, the model has spread across Europe, from Portugal and the Netherlands to Germany, Denmark and Spain, and beyond to Canada and New York City.

The Thistle, the UK’s first iteration, operates 365 days a year, and shares its premises with addiction services and social care teams.

As of June, 71.9% of drugs injected inside were cocaine, with heroin making up a further 20%. The users are overwhelmingly male. Most have been injecting for years; all are at risk.

Still, resistance remains. CNN spoke to several people in the area who were concerned about the facility’s opening and said it had encouraged more drug users to come to the area in the six months since opening.

Others, however, told CNN that they had noticed there were fewer needles and less discarded drug paraphernalia on the ground since the clinic opened.

Chief Inspector Max Shaw, of Police Scotland, told CNN that the force was “aware of long-standing issues in the area” and was “committed to reducing the harm associated with problematic substance use and addiction.” He added that officers would continue to work with local communities to address concerns.

For the nurses, doctors and support staff who work in the building, the mission remains immediate: delivering potentially life-saving support to those in need.

Source link