London

—

US President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin are heading to Alaska for pivotal talks that could unlock a long-sought peace deal between Russia and Ukraine.

A peace deal, or a simple thawing of relations between Moscow and Washington, could also pave the way for what, until recently, seemed fanciful to most American companies – doing business with Russia.

“I noticed (Putin’s) bringing a lot of business people from Russia, and that’s good,” Trump said aboard Air Force One on Friday. “I like that, because they want to do business, but they’re not doing business until we get the war solved.”

Anton Siluanov, Russia’s finance minister, and Kirill Dmitriev, a senior economic negotiator and head of Russia’s sovereign wealth fund, are among those attending the talks with Putin.

“If we make progress, I would discuss (business opportunities), because that’s one of the things that they would like; they’d like to get a piece of what I built in terms of the economy,” the US president told reporters.

But restarting business with a country that the West has largely turned into a diplomatic and economic pariah via sanctions will be no easy feat. Here’s why:

After Putin’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Western companies left Russia en masse in protest.

Since then, more than 1,000 global companies have either voluntarily exited or curtailed operations in Russia, according to a list compiled by the Yale School of Management.

Household US names like Apple (AAPL), Goldman Sachs (GS) and Mastercard (MA) were among those who left, yet there have been some holdouts continuing to do some business in the country.

The scale of the corporate exodus means there are simply fewer American companies in Russia to generate new business opportunities than before the war.

Meanwhile, Chinese firms including automakers and tech companies have filled the gap left by their Western counterparts. Russians have also turned to copy-cat versions of American brands. For example, Stars Coffee emerged after Starbucks (SBUX) exited in 2022, adopting an audaciously familiar logo of a woman with a star above her head.

So, if Western companies did return en masse, would Russian consumers welcome them?

Western sanctions have focused on hitting Moscow where it hurts: limiting the revenues it can collect from its massive exports of oil and natural gas.

Last year, those revenues accounted for 30% of Russia’s federal government budget, according to an analysis by The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

Oil and gas revenues remain “the single most important source of finance for the state coffers,” wrote Vitaly Yermakov, a senior research fellow at the Institute, in the February report.

The European Union, once a top Kremlin customer, has banned all seaborne imports of Russian crude oil, and whittled Moscow’s share of its natural gas imports delivered via pipeline to about 11% last year, from more than 40% in 2021. The bloc still imports Russian liquefied natural gas via sea tankers.

But Russia has adapted, re-routing its barrels of oil to alternate customers, like India and China. According to Vortexa, an energy data firm, Russia now accounts for 36% of India’s crude oil imports and is the country’s top supplier.

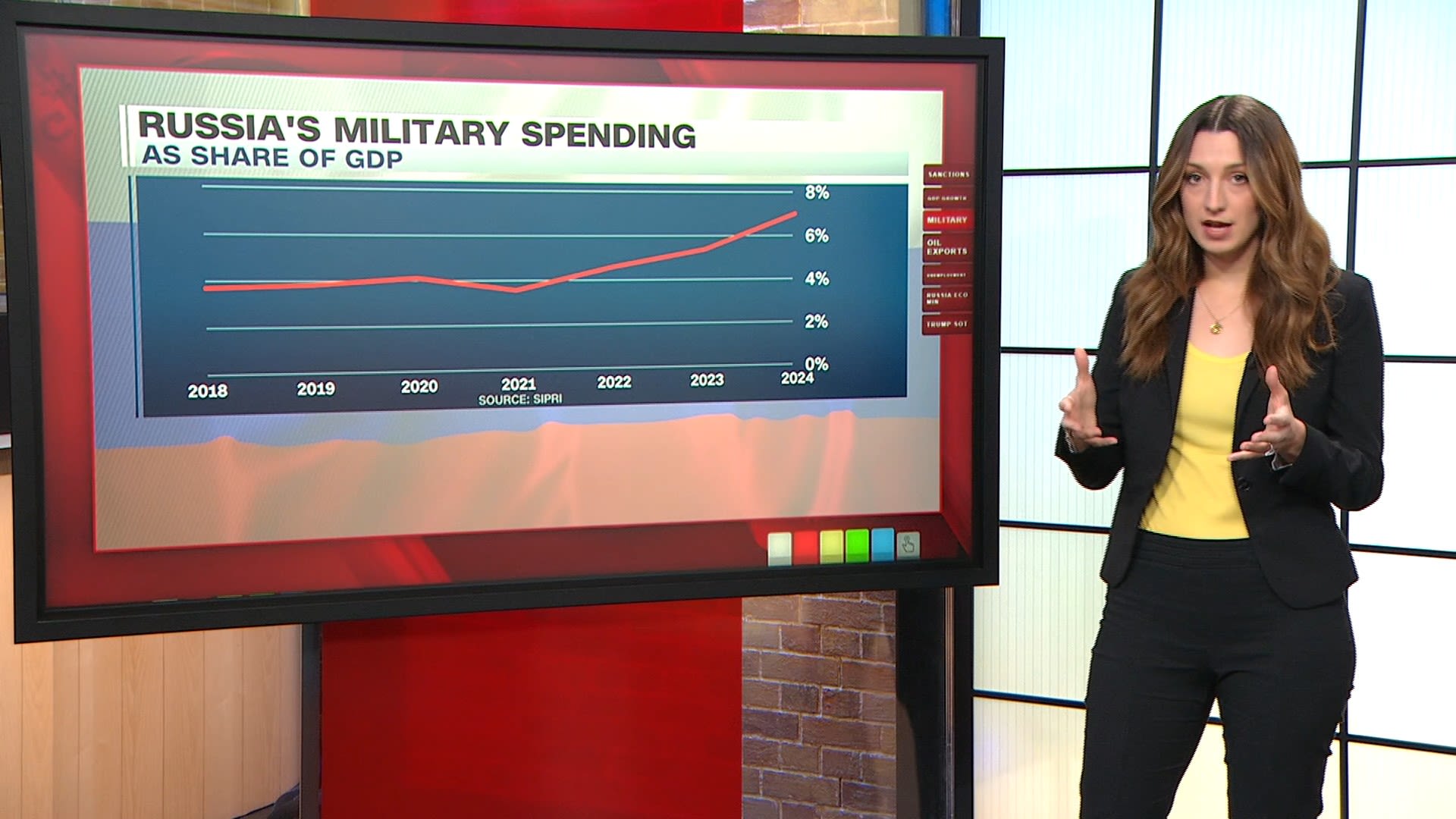

See how Russia’s economy has fared since the war

Trump has recently threatened to impose punishing tariffs on countries that continue to buy Moscow’s barrels to discourage the trade and force Putin – by economic necessity – to the negotiating table. But New Delhi has been defiant, saying that Russian oil is necessary for the energy security of its 1.4 billion-strong population.

One key sanction – a price cap on Russian oil imposed by the Group of Seven nations in 2022 – may be difficult for America to fully unwind without international support.

The cap is designed to dent Moscow’s revenues while still allowing its oil to flow to the global market. Companies located in the G7 are prevented from providing shipping, insurance and other services needed to export Russian seaborne oil unless it is priced below the threshold.

Simply doing business in Russia has become harder since the war.

Crucially, it has become more difficult for Russian banks to send and receive money from abroad. Shortly after the invasion, the United States, the EU, Britain and Canada jointly banned some Russian banks from the SWIFT messaging service — a high-security network connecting thousands of financial institutions around the world.

Janis Kluge, a researcher at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, told CNN in February that the United States wouldn’t be able to re-admit banned banks to the network without cooperation from the EU because SWIFT is based in Belgium.

Corruption has also worsened from already high levels. In 2021, nonprofit organization Transparency International put Russia in 136th place, tied with Liberia, in its ranking of 180 countries and territories for their perceived levels of public sector corruption. (A lower ranking indicates a higher level of corruption.)

But, by 2024, Russia had slid further down the Corruption Perceptions Index to 154th place, tied with Azerbaijan, Honduras and Lebanon.

American businesses contemplating a return to, or reinvestment in, Russia may then ask themselves: Would it be worth it?