Education

Trump’s dismantling of Education Department gives states ‘green light’ to pursue voucher programs

A growing number of red states have expanded their school voucher programs in recent years, a trend that is likely to only spike further amid a push led by President Donald Trump’s administration to return education “back to the states.”

Conservative education activists have long lauded such programs as a way to give greater control to parents and families. But public education advocates warn that the expansion of these voucher programs presents further risk to the broader school system as it faces peril from Trump’s dismantling of the Department of Education.

“Many states came into this administration with a track record of trying to privatize education, and I think they see this move to dismantle and defund the Department of Ed and President Trump’s support of school privatization as a green light to be more expansive in their approach moving forward,” said Hilary Wething, an economist at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute who closely studies the impact of voucher programs on public education.

Just last week, Texas enacted a statewide private school voucher program, becoming the 16th state to offer some form of a universal school choice program. In private school voucher programs, families can receive a certain amount of public money to use toward private K-12 school tuition or school supplies. In some states, such programs have previously come with limitations, including narrow eligibility, such as private schools that can accommodate families with children who have special needs or families that are below certain income levels.

Proponents of the program in Texas and others like it dub it a “universal voucher” program because it has no restrictions on who is eligible. Under the program, any family in the state may receive about $10,000 to pay for their children’s K-12 private school education. Texas’ program will launch in the 2026-27 school year.

Statewide voucher programs are far from a new phenomenon. But they have exploded in recent years amid a growing political effort by conservatives at the local, state and federal levels to boost “school choice” — the notion that parents should have far more options than only their neighborhood public schools.

Sixteen states offer at least one voucher program that has universal eligibility, while another 14 offer voucher programs with eligibility requirements, according to the Education Law Center, a public education advocacy group that is critical of voucher programs.

At least three states, Texas, Idaho and Tennessee, have enacted their universal programs this year, while in another eight states, attempts by conservative lawmakers to create new voucher programs or expand existing ones stalled or failed, according to the National Education Association, the nation’s largest teachers union.

“Even though this is not a new explosion of voucher laws, this year continues the explosion of vouchers … and even though the USDOE [dismantling] isn’t necessarily the one driving force, it’s definitely connected,” said Jessica Levin, the litigation director at the Education Law Center, which is assisting with lawsuits challenging Trump’s moves to dismantle the Department of Education. “The bottom line is that this is a concerted strategy on the part of those who want to defund and dismantle public schools and privatize public education.”

The most prominent argument made by critics of voucher programs is that they take public money that would have otherwise been allocated to help fund public schools and deliver it to private schools.

Private schools, they note, do not face most of the accountability requirements that public schools do under federal laws. For example, private schools retain the ability to refuse admission to students, are not required to provide individualized education plans to children with learning disabilities and are not required under law to provide disabled students or students facing disciplinary measures certain protections or due process rights.

At the same time, funding formulas for public schools are predominantly based on enrollment numbers. So, as students flee public schools — even if in just small numbers — overall funding decreases.

“The students who remain in public schools lose resources,” Levin said, while “voucher students lose rights.”

Meanwhile, Levin explained, voucher-driven pupil departures from public school means “you’re now concentrating higher-need, higher-cost kids in public schools that now have less funding.”

Those situations are now compounded by Trump’s moves to wind down the Education Department, which experts have said will further upend civil rights enforcement in schools as well as the distribution of billions of dollars to help impoverished and disabled students.

U.S. Department of Education spokesperson Savannah Newhouse said in an email to NBC News that “President Trump and Secretary [Linda] McMahon believe that our nation’s students will thrive when parents are given the freedom to choose a school setting that best fits their child’s academic needs.”

Newhouse added that the administration “will provide states with best practices on how they can expand educational opportunities and empower local leaders to implement customized policy that will benefit their communities the most.”

While some states have had voucher-like programs allowing families to use public money for parochial education dating back more than 100 years, modern voucher programs have been around for about 30 years, having launched in large part in the 1990s amid a grassroots conservative movement to increase options for parents unhappy with their local public schools.

But the Covid-19 pandemic emerged as a flashpoint for conservative education activists, who utilized widespread anger among parents unhappy with school closings and remote learning as a launchpad for new and expanded voucher programs across the nation.

School voucher proponents say the programs maximize choice for parents, who can use the funds to subsidize the cost of expensive private schools, which, they argue, deliver better outcomes for students. Supporters have also touted the programs as offering a market-based approach that helps promote the best schools and have argued that they have the potential to benefit low-income families or families with uniquely few options for public school.

Tommy Schultz, the CEO of the American Federation for Children, a conservative group that advocates for school voucher programs, told Fox News this week that universal voucher programs like the one enacted in Texas give parents “education freedom.”

He praised a similar program that Florida expanded in 2023, claiming it had caused the state’s public schools to “have gotten better.” Schultz denied that Texas’ program, or ones like it, would result in fewer resources for public schools, calling that “the same argument for 30 years” by public education advocates.

Andrew Mahaleris, a spokesperson for Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, said in an email that the Republican “made education freedom a priority because no one knows the needs of their child better than a parent.”

“When it comes to education, parents matter, and families deserve the ability to choose the best education opportunities for their children,” Mahaleris added. “The Governor signing school choice into law is an unprecedented victory for Texas families, students, and the future of our great state.”

But critics point to examples showing that universal school voucher programs are disproportionately used by wealthy families whose children are already enrolled in private schools, or that children in rural areas with few schools have limited options to put the money to use. They also point to studies that refute the claim that private schools deliver better outcomes for students.

In addition, enrollment in private schools, even with a voucher to help cover the cost, can still be prohibitively expensive for low-income families, they said.

Wething, of the EPI, said analyses have shown that between 60% and 90% of students who take advantage of universal-eligibility voucher programs across the U.S. were already enrolled in private school when they participated in the programs.

She warned of the harms she said programs like the one in Texas posed.

“As soon as you get rid of income limits or carveouts for, say, only low-income families or only students with disabilities, you basically open the gates for students who are already attending private school, or who already have enough income to attend private school, to now use state funding to subsidize their private school,” she said. “It’s kind of the next step in what we think of as this voucher evolution.”

Education

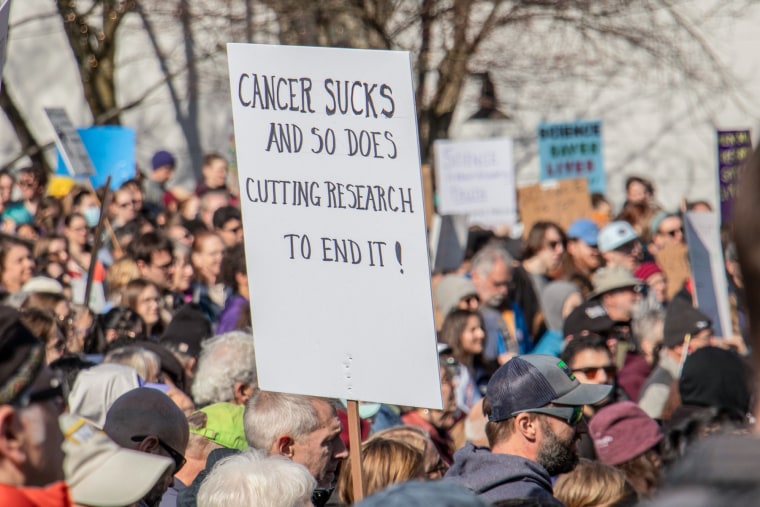

The best and brightest young scientists are looking beyond the U.S. as cuts hit home

Jack Castelli had it all figured out.

The University of Washington doctoral student had spent the past three years developing new gene-editing techniques that could spur immunity to the virus that causes AIDS. Early testing in mice showed promising results. His research group hoped it could develop into a treatment, or even a cure, for HIV.

Castelli, who is Canadian, saw two career paths after his graduation this spring: He could join a U.S. biotech company, or he could find a postdoctoral position at a U.S. university or research laboratory.

“This is where the money is at and where all the clinical trials are happening,” Castelli said, making the U.S. “the only place in my mind I could push that forward.”

Then the Trump administration’s science cuts hit.

And so, on a rainy late April day in Seattle, Castelli stood at a lectern before his friends and family and defended his doctoral thesis — about using stem cells to express antibodies against HIV — with his scientific life at a crossroads.

Should he join a lab in his native Canada? Accept recruiting calls to a European university? A Chinese biotech company? They were all possibilities now, and his U.S. visa is likely to expire in a few months’ time.

“I have a personal interest in Jack getting the best opportunity for himself, and as much as I’d love to say the U.S. is the place, I can’t necessarily say that right now,” said Jennifer Adair, who was Castelli’s principal investigator at the Fred Hutch Cancer Center, a partner institute to the university.Castelli speaks three languages fluently and completed two internships while earning his doctoral degree. He is a generous colleague and an exceptional scientist, Adair said.

But his uncertain future is hardly unique. The Trump administration’s slowdown in science funding — which stalled thousands of grants at the National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation, among other organizations — has left U.S.-based scientists and researchers scrambling to find homes for promising work that could lead to medical treatments and cures. Now many are looking abroad. As of May, Castelli had not made a decision on whether he’ll stay in the U.S.

The slowdown has forced the University of Washington, a top public university for biomedical research, to implement a hiring freeze, travel restrictions, class size reductions and furloughs. Some departments are pushing students to graduate sooner than expected. In a court filing, a university representative said it funds about 3,000 researchers through NIH grants.

Interviews with more than 20 graduate students, faculty members and university administrators at UW describe a research hub thrown into chaos. Other institutions have made similarly drastic moves, according to court filings in lawsuits that aim to thwart the cuts.

Many of those interviewed said a generation of scientists — and the innovations their research would bring — could be decimated.

“Really talented people are not able to get jobs; other really talented people are able to get jobs, but they’re choosing not to take them because of the craziness,” said David Baker, a professor of biochemistry at the University of Washington School of Medicine, who won the Nobel Prize in 2024 for protein research. “Why would you stay in a country where there’s not really an obvious commitment to science, when you could go somewhere else and be better funded and not worry about what you can read in the news or what email you’re going to get?”In an April 14 court filing, the university’s vice provost for research, Mari Ostendorf, said the campus mood had dimmed.

“Faculty and staff don’t know if their funding will be cut, if their research will be terminated, whether they will be able to attend conferences, or even whether they will continue to have jobs,” Ostendorf wrote. “Funding gaps have forced researchers to abandon studies, miss deadlines, or lose key personnel.”

A spokesperson for the National Institutes of Health declined to comment.

And there may be even more funding lost in the future due to Trump administration decisions. After a protest at the University of Washington campus Monday over the war in the Gaza Strip, the Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees NIH, announced that it was part of a task force reviewing UW’s response to the demonstration.

About 30 people were arrested after occupying a campus building Monday, according to the university, which condemned the protest in a statement and described it as “dangerous” and “violent.”

The Trump administration previously canceled federal grants at Columbia University during a similar review and has said Harvard University will receive no new grants until it makes a series of reforms, including changes to policies about protests and antisemitism.

Although the review was only announced Tuesday, the administration’s Task Force to Combat Anti-Semitism said in a news release that “the university must do more to deter future violence and guarantee that Jewish students have a safe and productive learning environment,” adding that it expected UW “to follow up with enforcement actions and policy changes.”

A university science laboratory operates like a small factory where workers are churning out ideas, research and data, rather than furniture or light bulbs. Traditionally, these labs’ primary customers are federal science agencies, like NIH or NSF.

Think of a lab’s principal investigator as akin to a company president. In the grant process, they must convince the government or private funders to buy their product — unique research — and then pay graduate students in wages and tuition.

“I’m like a small-business owner,” said Adair, who recently left Seattle to serve as a professor and associate director at the UMass Chan Medical School’s gene therapy center. “I have to pay myself. I have to pay my staff. I have to find the money to do the research.”In the first few months of 2025, funding for NIH grants has lagged the year prior by at least $2.3 billion, according to STAT News. NIH has also canceled grant applications as it targets politically disfavored topics like infectious diseases, according to critics.

That funding slowdown has forced many principal investigators to reduce their lab’s size.

“We’ve had to make personnel cuts,” said Alex Greninger, a professor of laboratory medicine at UW Medicine, adding that he had been forced to rescind a job offer to a postdoctoral researcher from China who had been doing research in his lab for nearly three years.

It cost the researcher her visa, he said. Another member of his lab left to take a job at a Chinese gene synthesis firm. Several have seen placements rescinded at other institutions.

“This is the first year where people didn’t get into graduate school,” Greninger said, about technicians in his lab who have completed undergraduate degrees, adding that they had done “everything right.”

Dr. Anna Wald, the head of allergy and infectious diseases at UW Medicine, the university’s school of medicine and hospital system, said several principal investigators in her department cut part of their own salaries to keep their staffers on.

Meanwhile, Adair paid out of her own pocket to send students to conferences that could advance their careers.

The uncertainty has also simply wasted time, some said.

“Everybody is spending a lot of time dealing with changes in how the university operates,” said Jakob Von Moltke, an associate professor of immunology at the University of Washington. “Everything just functions less efficiently and there’s less innovation.”

With so many professors uncertain about funding, many first-year graduate students seeking a lab are struggling to find positions. At some UW departments, first-year graduate students often rotate between labs for several months before they select a home for the following four or five years.

“A lot of people are scrambling to find a lab to settle into and a lot of faculty are unable to commit to taking students, or backing out of commitments,” said Dustin Mullaney, a first-year doctoral student studying molecular and cellular biology.

Still, many first-years consider themselves lucky — at least they got in. Most UW departments have reduced upcoming graduate classes by 25%-50%, according to court filings in a case filed by 16 state attorneys general aiming to restore the flow of NIH funding.

“I think we are going to lose most of a generation of scientists,” said Henry Mangapalli, a first-year doctoral student in the laboratory medicine department.

Meanwhile, doctoral students nearing graduation say they’re being recruited to move abroad.

Kristin Weinstein, a fourth-year doctoral student in the department of immunology working on autoimmune research, planned to graduate next year, find a postdoctoral research position at a U.S. university and eventually become a professor.

But now, faced with hiring freezes and shrinking labs, Weinstein said she’s considering moving her family, including an infant son, out of the U.S. Before UW’s austerity actions, Weinstein booked travel to Switzerland so she could present her research at the World Immune Regulation Meeting 2025, a key conference in her field.“What it turned into was a lot of informational interviewing,” Weinstein said. “I talked to faculty who are in Australia, faculty who are in Germany, faculty who are in Luxembourg and Denmark. … There was active recruiting happening.”

Baker, the Nobel winner who directs the Institute for Protein Design, said that more than 15 of his graduate students and postdoctoral researchers were aiming for new roles overseas. Meanwhile, other students have seen their research upended.

Nelson Niu, a fourth-year doctoral student in mathematics, said he had planned to spend six years teaching students and completing his thesis, a timeline sanctioned by his department. But on March 11 he received an email from his department chair saying the policy had changed for fourth-year students because of new financial realities, and people like Niu were now only guaranteed five years of funding.

“Jarring,” Niu said of the notice; now he’d have to pack two years of study into one.

Arjun Kumar, a third-year doctoral student studying why T cells lose their ability to fight off tumors, was working with National Cancer Institute researchers to potentially apply some of his research findings to a type of treatment pioneered there.

But Kumar said he lost weeks of time after the NIH placed a temporary communications freeze on federal researchers this winter.

“They were already working on key experiments for us and they already had data they couldn’t send us because they couldn’t email us,” Kumar said.Later, Kumar learned the NCI researchers no longer had the bandwidth to help.

“It was an exciting collaboration that was snuffed out in the moment,” Kumar said.

Washington is one of 16 states suing the NIH and HHS over its slowdown in grant funding. A judge will hear arguments Thursday as the state attorneys general seek a preliminary injunction.

Meanwhile, the pressure on scientists to leave the U.S. is only increasing. On Monday, the European Union launched a drive to attract scientists to Europe, and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced a commitment of $566 million to attract U.S. talent and “make Europe a magnet for researchers.”

“It has been really challenging to my identity as an American citizen to think about having to leave the country to pursue my career,” Weinstein said. “It feels like the American dream is dead.”

Education

Trump administration says Harvard will receive no new grants until it meets White House demands

WASHINGTON — Harvard University will receive no new federal grants until it meets a series of demands from President Donald Trump’s administration, the Education Department announced Monday.

The action was laid out in a letter to Harvard’s president and amounts to a major escalation of Trump’s battle with the Ivy League school. The administration previously froze $2.2 billion in federal grants to Harvard, and Trump is pushing to strip the school of its tax-exempt status.

Harvard has pushed back on the administration’s demands, setting up a closely watched clash in Trump’s attempt to force change at universities that he says have become hotbeds of liberalism and antisemitism.

In a press call, an Education Department official said Harvard will receive no new federal grants until it “demonstrates responsible management of the university” and satisfies federal demands on a range of subjects. It applies to federal research grants and not federal financial aid students receive to help cover tuition and fees.

The official spoke on condition of anonymity to preview the decision on a call with reporters.

Follow live politics coverage here

The official accused Harvard of “serious failures” in four areas: antisemitism, racial discrimination, abandonment of rigor and viewpoint diversity. To become eligible for new grants, Harvard would need to enter negotiations with the federal government and prove it has satisfied the administration’s demands.

The administration has demanded a series of changes to campus policy, including reforms to crack down on protesters and pursue more viewpoint diversity among faculty.

In a letter Monday to Harvard’s president, Education Secretary Linda McMahon accused the school of enrolling foreign students who showed contempt for the U.S.

“Harvard University has made a mockery of this country’s higher education system,” McMahon wrote.

Harvard’s president has previously said he will not bend to government’s demands. The university sued to halt its funding freeze last month.

Harvard’s suit called the funding freeze “arbitrary and capricious,” saying it violated its First Amendment rights and the statutory provisions of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.

The Trump administration said previously that Harvard would need to meet a series of conditions to keep almost $9 billion in grants and contracts.

The school in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has an endowment of $53 billion, the largest in the country. Across the university, federal money accounted for 10.5% of revenue in 2023, not counting financial aid such as grants and student loans.

Education

New college grads face a tougher job market — again

This year’s new college graduates are heading into a tougher job market than last year’s — who had it worse off than the class before that — just as the Trump administration cracks down on student loan repayments.

Recent grads’ unemployment rate was 5.8% as of March, up from 4.6% a year earlier, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York reported last week. The share of new graduates working jobs that don’t require their degrees — a situation known as “underemployment” — hit 41.2% in March, rising from 40.6% that same month in 2024.

“Right now things are pretty frozen,” Allison Shrivastava, an economist at Indeed Hiring Lab, said of entry-level prospects. “A lot of employers and job seekers are both kind of deer-in-headlights, not sure what to do.”

Employers and job seekers are both kind of deer-in-headlights, not sure what to do.

Allison Shrivastava, economist, Indeed Hiring Lab

That squares with Julia Abbott’s experience.

“I just feel pretty screwed as it is right now,” said the psychology major who’s graduating this month from James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia. She said she’s applied to over 200 roles in social media and marketing, but “minimal interviews come out of it.”

Internship postings typically rise sharply in early spring, but they’re lagging 11 percentage points behind last year’s levels, Indeed said in April. The hiring platform sees demand for interns as a stronger gauge of new grads’ job prospects than entry-level postings, which increasingly target people with at least a few years’ experience.

In a worrying sign for the class of 2025, internship openings are “far below where they were in 2023 and 2022, when the labor market was exceptionally competitive,” Shrivastava said.

Young college grads have historically seen lower unemployment levels than the labor force overall, and they still do. But as The Atlantic pointed out Wednesday, this gap has narrowed to a record low, taking some of the shine off the traditional benefits of a bachelor’s degree.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration is restarting the “involuntary” repayment of federal student loans in default, a move that could sap money from paychecks, tax refunds, Social Security payments and disability and retirement benefits from millions of borrowers.

Repayments were paused during President Donald Trump’s first term in 2020 in response to Covid-19. The pandemic-era reprieve from forced collections ends Monday, just as a new TransUnion report finds a record share of federal student loan borrowers are 90 days or more past due and at risk of default — at 20.5% as of February, up 10 percentage points from five years earlier.

The debt crackdown comes as workers across the labor force confront a tougher hiring landscape. Employers added a better-than-expected 177,000 jobs in April, government data showed Friday, but analysts were quick to flag warning signs ahead.

Average pay growth has slowed to a crawl, and unemployment metrics indicate it’s taking longer for people looking for work to secure it. While the latest jobs numbers point to a “resilient” labor market, “we should curb our enthusiasm going forward given the backdrop of trade policies that will likely be a drag on the economy,” Olu Sonola, head of U.S. economic research at Fitch Ratings, said in a statement Friday. “The outlook remains very uncertain.”

The murky jobs forecast coincides with broader economic turbulence fueled by Trump’s ongoing trade war.

A slew of major companies have warned about tariff impacts in recent days. All but the wealthiest households are tightening their budgets, and consumer outlooks plunged to a 13-year low in a closely watched Conference Board survey released Tuesday. Some of the spending that is taking place reflects shoppers and businesses racing to make purchases before tariffs drive up costs for everything from cars to frozen fish and fireworks.

These headwinds are making many employers increasingly cautious about hiring young graduates.

Employers have pulled back plans to hire more new grads over just the last six months, according to a February and March survey by the National Association of Colleges and Employers, which polled major companies including Chevron, PepsiCo and Southwest Airlines. While most said their new-grad recruitment plans are holding steady, the share of respondents planning to expand entry-level hiring dipped to 24.6% this spring. That’s down from 27% last fall and the lowest rate since autumn 2020, during the depths of the pandemic.

In March, NACE released salary projections showing a mixed picture for the class of 2025, with social sciences graduates set to see a 3.6% drop in pay since last year, while agriculture and natural resources majors were on track for a 2.8% bump over their ’24 predecessors. The estimates, however, were based on employer survey data from last fall, weeks before Trump took office.

“I’m not surprised that new hiring is being restricted,” said Andy West, a senior partner at the consulting firm McKinsey who advises CEOs on corporate strategy and finance. He said some clients are increasingly discussing ways to “reallocate resources” amid tariffs and other macroeconomic worries, he said. As employers hunt for cost cuts and stability, many tend to zero in on expenses that fluctuate over time, including payrolls.

It just feels really scary, like walking into this world and not having something set out for me.

Julia Abbott, James Madison University, class of 2025

“When it comes to hiring and talent, often these are very short-term decisions around slowing down,” he said.

Class of ’25 job seekers are adjusting their expectations to the tighter market.

More than half have ditched the “dream job” plans they entered college with, according to a February survey by the grads-focused hiring platform Handshake. And 56% of current seniors are somewhat or very pessimistic about launching into the workforce right now. That’s about the same share as last year, but outlooks are down more sharply in fields like computer science, where over a quarter of seniors with that major voiced extreme pessimism.

Anxiety around landing a first full-time job is common among college students, but the deep uncertainty this year threatens to put a damper on commencement season.

“I can’t really celebrate my past four years,” said Abbott, the JMU senior. “It just feels really scary, like walking into this world and not having something set out for me.”

-

Conflict Zones2 days ago

Conflict Zones2 days agoRussia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 1,170 | Russia-Ukraine war News

-

Conflict Zones2 days ago

Conflict Zones2 days ago‘Missiles in skies’: Panic in Indian frontier cities as war clouds gather | India-Pakistan Tensions News

-

Europe1 day ago

Europe1 day agoPope Leo XIV urges cardinals to make themselves ‘small’ in first mass as pontiff

-

Conflict Zones1 day ago

Conflict Zones1 day agoWho are the armed groups India accuses Pakistan of backing? | Armed Groups News

-

Africa1 day ago

Africa1 day agoRussia stages massive victory day parade, Putin hails troops in Ukraine as foreign leaders attend

-

Conflict Zones1 day ago

Conflict Zones1 day ago‘Slippery slope’: How will Pakistan strike India as tensions soar? | India-Pakistan Tensions News

-

Europe1 day ago

Europe1 day agoUkraine’s Western allies pile pressure on Putin, threatening sanctions if he refuses 30-day truce

-

Lifestyle1 day ago

Lifestyle1 day agoTwo dolls instead of 30? Toys become the latest symbol of Trump’s trade war