Lifestyle

Sleep training for teens? These schools teach how to get enough rest

MANSFIELD, Ohio (AP) — The topic of a new course at Mansfield Senior High School is one that teenagers across the country are having trouble with: How to Get to Sleep.

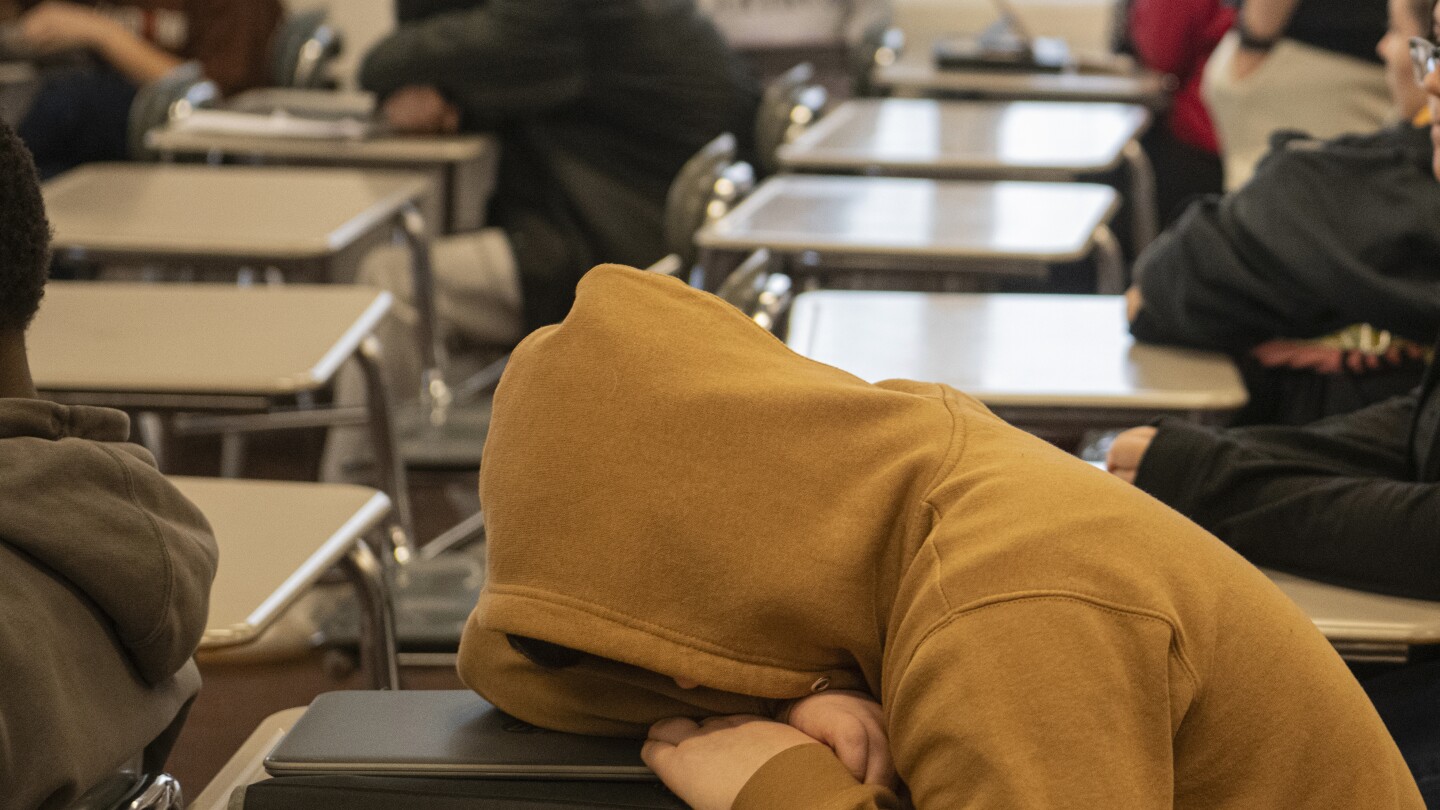

One ninth grader in the class says his method is to scroll through TikTok until he nods off. Another teen says she often falls asleep while on a late-night group chat with friends. Not everyone takes part in class discussions on a recent Friday; some students are slumped over their desks napping.

Sleep training is no longer just for newborns. Some schools are taking it upon themselves to teach teenagers how to get a good night’s sleep.

“It might sound odd to say that kids in high school have to learn the skills to sleep,” says Mansfield health teacher Tony Davis, who has incorporated a newly released sleep curriculum into a state-required high school health class. “But you’d be shocked how many just don’t know how to sleep.”

Adolescents burning the midnight oil is nothing new; teens are biologically programmed to stay up later as their circadian rhythms shift with puberty. But studies show teenagers are more sleep deprived than ever, and experts believe it could be playing a role in the youth mental health crisis and other problems plaguing schools, including behavioral and attendance issues.

“Walk into any high school in America and you will see kids asleep. Whether it’s on a desk, outside on the ground or on a bench, or on a couch the school has allotted for naps — because they are exhausted,” says Denise Pope, a senior lecturer at Stanford Graduate School of Education. Pope has surveyed high school students for more than a decade and leads parent sessions for schools around California on the importance of teen sleep. “Sleep is directly connected with mental health. There is not going to be anyone who argues with that.”

How much sleep do teens need?

Adolescents need between eight and 10 hours of sleep each night for their developing brains and bodies. But nearly 80% of teens get less than that, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has tracked a steady decline in teen sleep since 2007. Today, most teens average 6 hours of sleep.

Research increasingly shows how tightly sleep is linked to mood, mental health and self-harm. Depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts and behavior go up as sleep goes down. Multiple studies also show links between insufficient sleep and sports injuries and athletic performance, teen driving accidents, and risky sexual behavior and substance use, due in part to impaired judgment when the brain is sleepy.

For years, sleep experts have sounded an alarm about an adolescent sleep crisis, joined by the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the CDC and others. As a result, some school districts have shifted to later start times. Two states — California and Florida — have passed laws that require high schools to start no earlier than 8:30 a.m. But simply telling a teenager to get to bed earlier doesn’t always work, as any parent can attest: They need to be convinced.

That’s why Mansfield City Schools, a district of 3,000 students in north-central Ohio, is staging what it calls “a sleep intervention.”

‘Sleep to Be a Better You’

The district’s high school is piloting the new curriculum, “Sleep to Be a Better You,” hoping to improve academic success and reduce chronic absences, when a student misses more than 10% of the school year. The rate of students missing that much class has decreased from 44% in 2021 but is still high at 32%, says Kari Cawrse, the district’s attendance coordinator. Surveys of parents and students highlighted widespread problems with sleep, and an intractable cycle of kids going to bed late, oversleeping, missing the school bus and staying home.

The students in Davis’ classroom shared insights into why it’s hard to get a good night’s sleep. An in-class survey of the 90 students across Davis’ five classes found over 60% use their phone as an alarm clock. Over 50% go to sleep while looking at their phones. Experts have urged parents for years to get phones out of the bedroom at night, but national surveys show most teens keep their mobile phones within reach — and many fall asleep holding their devices.

During the six-part course, students are asked to keep daily sleep logs for six weeks and rate their mood and energy levels.

Freshman Nathan Baker assumed he knew how to sleep, but realizes he had it all wrong. Bedtime meant settling into bed with his phone, watching videos on YouTube or Snapchat Spotlight and often staying up past midnight. On a good night, he got five hours of sleep. He’d feel so drained by midday that he’d get home and sleep for hours, not realizing it was disrupting his nighttime sleep.

“Bad habits definitely start around middle school, with all the stress and drama,” Baker says. He has taken the tips he learned in sleep class and been amazed at the results. He now has a sleep routine that starts around 7 or 8 p.m.: He puts away his phone for the night and avoids evening snacks, which can disrupt the body’s circadian rhythm. He tries for a regular bedtime of 10 p.m., making sure to close his curtains and turn off the TV. He likes listening to music to fall asleep but has switched from his previous playlist of rousing hip hop to calmer R&B or jazz, on a stereo instead of his phone.

“I feel a lot better. I’m coming to school with a smile on my face,” says Baker, who is now averaging seven hours’ sleep each night. “Life is so much more simple.”

There are scientific reasons for that. Studies with MRI scans show the brain is under stress when sleep-deprived and functions differently. There is less activity in the pre-frontal cortex, which regulates emotions, decision making, focus and impulse control and more activity in the emotional center of the brain, the amygdala, which processes fear, anger and anxiety.

Parents and teens themselves often aren’t aware of the signs of sleep deprivation, and attribute it to typical teen behavior: Being irritable, grumpy, emotionally fragile, unmotivated, impulsive or generally negative.

Think of toddlers who throw temper tantrums when they miss their naps.

“Teenagers have meltdowns, too, because they’re tired. But they do it in more age-appropriate ways,” says Kyla Wahlstrom, an adolescent sleep expert at the University of Minnesota, who has studied the benefits of delayed school start times on teen sleep for decades. Wahlstrom developed the free sleep curriculum being used by Mansfield and several Minnesota schools.

Social media isn’t only to blame

Social media has been blamed for fueling the teen mental health crisis, but many experts say the national conversation has ignored the critical role of sleep.

“The evidence linking sleep and mental health is a lot tighter, more causal, than the evidence for social media and mental health,” says Andrew Fuligni, a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles, and co-director at UCLA’s Center for the Developing Adolescent.

Nearly 70% of Davis’ Mansfield students said they regularly feel sleepy or exhausted during the school day. But technology is hardly the only reason. Today’s students are overscheduled, overworked and stressed out, especially as they get closer to senior year and college applications.

Chase Cole, a senior at Mansfield who is taking three advanced placement and honors classes, is striving for an athletic scholarship to play soccer in college. He plays on three different soccer leagues and typically has practice until 7 p.m., when he gets home and needs a nap. Cole wakes up for dinner, then dives into homework for at least three hours. He allows for five-minute phone breaks between assignments and winds down before bed with video games or TV until about 1 a.m.

“I definitely need to get more sleep at night,” says Cole, 17. “But it’s hard with all my honors classes and college stuff going on. It’s exhausting.”

There aren’t enough hours in the day to sleep, says sophomore Amelia Raphael, 15. A self-described overachiever, Raphael is taking physics, honors chemistry, algebra and trigonometry and is enrolled in online college classes. Her goal is to finish her associate degree by the time she graduates high school.

“I don’t want to have to pay for college. It’s a lot of money,” says Raphael, who plays three sports and is in student council and other clubs.

She knows she’s overscheduled. “But if you don’t do that, you’re kind of setting yourself up for failure. There is a lot of pressure on doing everything,” said Raphael, who gets to bed between midnight and 2 a.m. “I am giving up sleep for that.”

___

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Lifestyle

The 250th anniversary of the Battles of Lexington and Concord opens debate over US independence

NEW YORK (AP) — The American Revolution began 250 years ago, in a blast of gunshot and a trail of colonial spin.

Starting with Saturday’s anniversary of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the country will look back to its war of independence and ask where its legacy stands today.

The semiquincentennial comes as President Donald Trump, the scholarly community and others divide over whether to have a yearlong party leading up to July 4, 2026, as Trump has called for, or to balance any celebrations with questions about women, the enslaved and Indigenous people and what their stories reveal.

The history of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts is half-known, the myth deeply rooted.

What exactly happened at Lexington and Concord?

Reenactors may with confidence tell us that hundreds of British troops marched from Boston in the early morning of April 19, 1775, and gathered about 14 miles (22.5 kilometers) northwest on Lexington’s town green.

Firsthand witnesses remembered some British officers yelled, “Thrown down your arms, ye villains, ye rebels!” and that amid the chaos a shot was heard, followed by “scattered fire” from the British. The battle turned so fierce that the area reeked of burning powder. By day’s end, the fighting had continued around 7 miles (11 kilometers) west to Concord and some 250 British and 95 colonists were killed or wounded.

But no one has learned who fired first, or why. And the revolution itself was initially less a revolution than a demand for better terms.

Woody Holton, a professor of early American history at the University of South Carolina, says most scholars agree the rebels of April 1775 weren’t looking to leave the empire, but to repair their relationship with King George III and go back to the days preceding the Stamp Act, the Tea Act and other disputes of the previous decade.

“The colonists only wanted to turn back the clock to 1763,” he said.

Stacy Schiff, a Pulitzer Prize winning historian whose books include biographies of Benjamin Franklin and Samuel Adams, said Lexington and Concord “galvanized opinion precisely as the Massachusetts men hoped it would, though still it would be a long road to a vote for independence, which Adams felt should have been declared on 20 April 1775.”

But at the time, Schiff added, “It did not seem possible that a mother country and her colony had actually come to blows.”

A fight for the ages

The rebels had already believed their cause greater than a disagreement between subjects and rulers. Well before the turning points of 1776, before the Declaration of Independence or Thomas Paine’s boast that “We have it in our power to begin the world over again,” they cast themselves in a drama for the ages.

The so-called Suffolk Resolves of 1774, drafted by civic leaders of Suffolk County, Massachusetts, prayed for a life “unfettered by power, unclogged with shackles,” a fight that would determine the “fate of this new world, and of unborn millions.”

The revolution was an ongoing story of surprise and improvisation. Military historian Rick Atkinson, whose “The Fate of the Day” is the second of a planned trilogy on the war, called Lexington and Concord “a clear win for the home team,” if only because the British hadn’t expected such impassioned resistance from the colony’s militia.

The British, ever underestimating those whom King George regarded as a “deluded and unhappy multitude,” would be knocked back again when the rebels promptly framed and transmitted a narrative blaming the royal forces.

“Once shots were fired in Lexington, Samuel Adams and Joseph Warren did all in their power to collect statements from witnesses and to circulate them quickly; it was essential that the colonies, and the world, understand who had fired first,” Schiff said. “Adams was convinced that the Lexington skirmish would be ‘famed in the history of this country.’ He knocked himself out to make clear who the aggressors had been.”

A country still in progress

Neither side imagined a war lasting eight years, or had confidence in what kind of country would be born out of it. The founders united in their quest for self-government but differed how to actually govern, and whether self-government could even last.

Americans have never stopped debating the balance of powers, the rules of enfranchisement or how widely to apply the exhortation, “All men are created equal.”

“I think it’s important to remember that the language of the founders was aspirational. The idea that it was self-evident all men were created equal was preposterous at a time when hundreds of thousands were enslaved,” said Atkinson, who cites the 20th-century poet Archibald MacLeish’s contention that “democracy is never a thing done.”

“I don’t think the founders had any sense of a country that some day would have 330 million people,” Atkinson said. “Our country is an unfinished project and likely always will be.”

Lifestyle

Sweets from the sky! A helicopter marshmallow drop thrills kids in suburban Detroit

ROYAL OAK, Mich. (AP) — It’s spring in Detroit — warm weather, a few clouds, and a 100% chance of marshmallow downpours.

The source? A helicopter zooming above the green lawn of Worden Park on Friday, unloading sack-fulls of fluffy treats for hundreds of kids waiting eagerly below, some clutching colorful baskets or wearing rabbit ears.

The children cheered and pointed as the helicopter clattered by on its way to the drop zone. Volunteers in yellow vests made sure kids didn’t rush in and start grabbing marshmallows until after the deluge was complete.

For anyone worried about hygiene, don’t fret. The annual Great Marshmallow Drop isn’t about eating the marshmallows — kids could exchange them for a prize bag that included a water park pass and a kite.

The marshmallow drop has been held for over three decades in the Detroit suburb of Royal Oak, Michigan, hosted by Oakland County Parks.

One toddler, Georgia Mason, had no difficulty procuring a marshmallow at her first drop, her dad Matt said.

“Probably the most exciting part was seeing the helicopters. But once we saw the marshmallows drop, we got really excited,” Matt Mason said.

“And, yeah, we joined the melee,” he said, “We managed to get one pretty easy.”

Organizers said 15,000 marshmallows were dropped in all.

The helicopter made four passes, dropping marshmallows for kids in three age categories: 4-year-olds and younger, 5-7-year-olds, and those ages 8 to 12. A drop for kids of all ages with disabilities came later in the day.

“We do it because it’s great for community engagement,” Oakland County recreation program supervisor Melissa Nawrocki said.

“The kids love it,” she continued. “The looks on their faces as they’re picking up their marshmallow and turning in the marshmallow for prizes is great.”

Lifestyle

AP report: Superman comics have religious and moral themes

Superman comics are not overtly religious. Yet faith and morality have been baked into this superhero character who was born Kryptonian, raised Methodist and created by two young Jewish men in 1930s Cleveland.

Superman’s character has been portrayed in the mold of Christ and Moses given how he constantly upholds the ideals of self-sacrifice, powerful leadership and compassion. While scholars, comic book writers and fans alike are struck by the religious undertones in Superman comics, they all agree that what sets Superman apart is his ability to bring hope in a hopeless world.

Superman Day and the ‘Superman’ summer movie release

Friday (April 18) marks the 87th anniversary of the original superhero’s birth. It also is the date Superman made his debut in an Action Comics issue.

There is much excitement in the Superman fanverse this year because of the much-anticipated ‘Superman’ movie directed by James Gunn, starring David Corenswet, the first Jewish actor to play Superman in a major film.

On his Instagram page on April 18, 2024, Gunn shared a photo of himself, Corenswet and Rachel Brosnahan who plays Lois Lane in the upcoming film, reading among several comic books, a reproduction of Action Comics #1 — the very first one featuring the Man of Steel.

In his Instagram post, Gunn also paid tribute to the superhero, saying: “He gave us someone to believe in, not because of his great physical power, but because of his character and determination to do right no matter what.”

Gunn’s film promises a return to a version of a vulnerable Superman who is rooted in values espoused by most faiths — goodness, compassion and hope.

Superman’s Jewish roots

Samantha Baskind, professor of art history at Cleveland State University, is Jewish and sees numerous parallels between Superman’s origin story and the history of Jews.

She says Superman’s solitary flight from Krypton in a small spacecraft is reminiscent of how Moses’ mother placed him in a papyrus basket and left him on the Nile, seeing it as his best chance of survival.

Some also compare Superman’s backstory to the Kindertransport, she said, referring to a humanitarian rescue program that transported nearly 10,000 children, mostly Jewish, from Nazi-controlled territories to Great Britain in 1938 and 1939. In Superman’s Kryptonian name, Kal-El, chosen by his original Jewish creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the “El” in Hebrew connotes God.

“There’s also the thinking that Siegel and Shuster created Superman because they were these two, skinny, young Jewish men who couldn’t go out and fight Hitler, but Superman fought Nazis on the cover of their comic books,” Baskind said.

In some early editions, Superman held Hitler by his Nazi uniform as he begged for mercy.

Strong appeal to diverse groups

Superman is relatable to diverse populations regardless of religion, race or ethnicity.

Gene Luen Yang, who has written several Superman comics, sees his own experience as a Chinese American mirrored in Superman’s story — caught between two worlds and two cultures. Yang says he had one name at home and another at school, just like Superman. So, even though he is a practicing Catholic, Yang says he relates more to Superman’s Jewish roots.

Despite the religious undertones, Superman also appeals to those who are religiously unaffiliated, said Dan Clanton, professor of religious studies at Doane University in Nebraska, adding that the superhero’s story “truly encapsulates American civil religion.”

Neal Bailey, a longtime contributor to Superman Homepage, a fan site, is an atheist. He views Superman as a “philosophical pragmatist” with the ability to solve the most complex problems with the least amount of harm.

“He actually goes beyond religion to see our commonalities,” Bailey said. “Superman wouldn’t care about people’s religious beliefs. He would care more about whether they are living up to their human potential.”

Superman inspires humans to do better

Grant Morrison, one of the best-known writers of Superman comic books, said in a 2008 interview that humans become what they imitate, which is why he made Superman an inspirational character.

Superheroes have received less-than-flattering treatment in recent films and television shows. For example, in “The Boys,” a comic book turned Amazon Prime series, the Superman-like character, Homelander, is a government-sponsored hero whose smiling exterior conceals the heart of a sadist. Gunn’s Superman is expected to change that trajectory with a superhero who will reinforce the character’s core value of preserving life at any cost.

An altruistic view of Superman can be found in the recently concluded “Superman & Lois” television series on the CW Network in which after defeating Lex Luthor in a final battle, the couple settles down in a small town and starts a foundation to help others.

“I didn’t just want to be a hero that saves people,” the Superman character played by Tyler Hoechlin says in an epilogue to the series. “I wanted to connect with them. To change their lives for the better.”

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

-

Conflict Zones2 days ago

Conflict Zones2 days agoHaiti in ‘free fall’ as violence escalates, rights group warns | Armed Groups News

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoJu Wenjun: Chinese grandmaster makes history by winning fifth Women’s World Chess Championship

-

Lifestyle2 days ago

Lifestyle2 days agoLook inside Maine’s ‘Sistine Chapel’ with 70-year-old frescoes

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoBarcelona player Mapi León banned for two matches after appearing to touch the groin of an opponent

-

Sports1 day ago

Sports1 day agoAaron Rodgers ‘not holding anybody hostage’ as he decides his future, retirement a possibility

-

Europe2 days ago

Europe2 days agoTrump blasts Fed Chair Powell, saying his ‘termination cannot come fast enough’

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoAaron Boupendza: 28-year-old former MLS player dies after falling from 11th floor balcony in China

-

Education21 hours ago

Education21 hours agoHarvard’s battle with the Trump administration is creating a thorny financial situation