Africa

Researchers study using planes to cool the earth amidst global warming

As global temperatures rise, extreme weather is forcing families from their homes.

Floods, hurricanes and melting glaciers are displacing communities across the planet.

Some scientists are researching ways to deal with climate change by manipulating the world’s atmosphere or oceans.

Known as geoengineering, it’s often rejected because of potential side effects, and is usually mentioned not as an alternative to reducing carbon pollution, but in addition to emission cuts.

One idea is to reflect sunlight away from the Earth before it can heat the surface – a process known as stratospheric aerosol injection.

A new study by University College London researchers suggests that this could be done using planes already in service today, rather than developing costly new aircraft to reach the highest parts of the atmosphere.

Stratospheric aerosol injection would work by releasing tiny particles into the atmosphere’s dry, stable upper layer called the stratosphere.

These particles would scatter sunlight back into space, reducing the amount reaching the Earth’s surface and helping to cool the planet.

Previous research focused on injecting aerosols high above the tropics, at altitudes of 20 kilometres or more, which is beyond the reach of most existing planes.

But the new study found that injecting lower down, around 13 kilometres, near the poles, could still have a significant impact.

It could mean aircraft like the Boeing 777, which is already capable of reaching these altitudes, could be adapted for the task.

Alistair Duffey, a PhD researcher at UCL, led the study.

He says: “So our study examined a climate intervention technique called stratospheric aerosol injection, which is an idea to cool down the planet by adding a layer of small reflective particles, aerosols, into the high atmosphere. Those particles would reflect a small amount, perhaps 1% of the incoming sunlight. And there was good evidence that this could be used to cool the planet, and perhaps to reduce some climate impacts on vulnerable people around the world.”

Using the UK’s advanced Earth System Model, researchers simulated injecting sulphur dioxide (a gas that quickly transforms into reflective sulphate aerosols) into the stratosphere over the polar regions during their respective spring and summer seasons.

The study showed that despite the lower altitude, it would still be possible to cool the planet by around 0.6 degrees Celsius.

This is roughly the same as the temporary cooling after the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991, when volcanic gases injected into the atmosphere caused global temperatures to dip.

The researchers examined how the effectiveness of cooling changes depending on where and how high the particles are released, as well as how much sulphur dioxide would be needed.

“What we were interested in is understanding the trade-off between the difficulty, the logistical challenge of doing this and the climate impacts on the ground. So in particular, we wanted to understand how, if you could get to different altitudes in the sky, how the level of impact on the ground would vary depending on how high we could go. In general, it’s harder to do this at high altitudes. So our central finding was that if we were limited to using existing large aircraft and therefore limited to altitudes of up to around 13 kilometres, we found that there was still meaningful climate impacts. We could still cool the planet meaningfully with plausible injection magnitudes of aerosols.”

The cooling effect comes from a chain of chemical reactions.

Once sulphur dioxide is released into the dry stratosphere, it reacts with water vapour and oxygen to form sulphuric acid, which then forms microscopic droplets — sulphate aerosols.

These aerosols remain suspended for months, reflecting sunlight away from Earth.

Eventually, they fall into the lower atmosphere and are washed out by rain — mostly as diluted acid rain.

“We are imagining releasing sulphur dioxide, which is a gas, which would react with water vapour and oxidise into sulfuric acid, which then dissociates and part of that sulfuric acid is the sulphate aerosol, which this kind of small liquid droplet. They tend to produce a size distribution in the stratosphere, which makes them good reflectors of sunlight. Those sulphate aerosols then slowly sediment downwards through the stratosphere and ultimately once they re-enter the troposphere, the part of the atmosphere we live in, most of them rain out so they come out in water and as acid rain essentially.”

While the chemical processes are well understood, the engineering challenges are significant.

Delivering large volumes of sulphur dioxide safely at high altitude would require modifying existing aircraft or building entirely new ones.

Creating new specialist aircraft capable of reaching 20 kilometres would likely take a decade and billions of pounds in development costs.

Instead, the researchers believe adapting existing aircraft could provide a faster and cheaper option.

But even this would require careful redesign to allow for planes to safely store and release a toxic gas at high altitudes without posing risks to crew, passengers or the environment.

“In our case, if you were using existing aircraft, then there would still be a modification programme required. You’d need some way to vent the slipper dioxide and to carry it safely. It’s a toxic gas, right? If you release this at ground level, it could be quite harmful. So there are definitely big engineering challenges, but they will be less intensive than the higher altitude deployment.”

The UCL researchers behind the study stress that stratospheric aerosol injection would not be a substitute for cutting emissions and would carry serious risks if not carefully managed.

However, other researchers, such as Raymond Pierrehumbert, Professor of Physics at University of Oxford, are sceptical about the the risks posed by using geoengineering to limit the most dangerous impacts of climate change.

He says: “Carbon dioxide will continue to affect the climate and give us warming for thousands of years, but the stratospheric aerosols fall out in a matter of a year or so. And so if you get into a situation where you rely on it, where you’re relying on stratospheric aerosol injection, you’re really locking humanity into doing it without fail for centuries at least. And that’s a very perilous situation to be in. And if you do it at a time when we haven’t yet reached net zero, then you have to do more of it each and every year. And if you ever stop, you get hit in the face with massive catastrophic warming very quickly.”

There are concerns that relying on aerosol injection could trap future generations into a risky, long-term commitment, with dangerous consequences if it’s ever interrupted.

“Among other things, when you deploy stratospheric aerosol injection, you can change atmospheric circulation patterns. And so this can do things like disrupt precipitation patterns, cause droughts in some places, cause excessive flooding in other places,” cautions Pierrehumbert.

Groups from the U.S. National Academy of Sciences to the United Nations Environment Programme have looked at the ethics, side effects, legal complications and benefits of geoengineering with various degrees of skepticism and cautious interest.

Africa

Red Cross escorts hundreds of stranded Congolese soldiers from rebel-controlled city to capital

Hundreds of stranded Congolese soldiers and police officers, along with their families, were being transferred from the rebel-controlled city of Goma in eastern Congo to the capital, the International Committee of the Red Cross announced Wednesday.

The soldiers and police officers have been taking refuge at the United Nations Stabilisation Mission in Congo’s base since January, when the decades-long conflict in eastern Congo escalated as the Rwanda-backed M23 rebels advanced and seized the strategic Goma.

The operation is the result of an agreement reached between the Congolese government, the rebels, the U.N. mission and the ICRC, which was called upon as a neutral intermediary, the Red Cross said in a statement. Upon arrival in Kinshasa, the soldiers, police officers and their families will be taken in by Congolese authorities, it added.

Myriam Favier, the ICRC chief in Goma, said during a press briefing Wednesday that the transfer from Goma to Kinshasa, about 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles) to the west, is expected to last several days.

The announcement was greeted with profound relief.

“We were disarmed because we had no choice, but we hope to reach Kinshasa,” a Congolese soldier told The Associated Press over the phone, ahead of his transfer. “As soldiers, we are always ready to defend our homeland. We lost a battle, not the war,” he said.

He spoke on condition of anonymity because he was still in the rebel-controlled area and not allowed to speak to reporters.

Sylvain Ekenge, spokesperson for Congo’s armed forces, welcomed the initiative in a statement on Wednesday.

“The Congolese Armed Forces hopes that this operation will be carried out in strict compliance with the commitments made,” he said, thanking the ICRC for its role.

For security reasons, no media outlets were allowed to film or photograph the operation.

The news of the ICRC’s escort comes amid persistent tensions in eastern Congo, where fighting between Congo’s army and M23 continues, despite both sides having agreed to work toward a truce earlier this month.

On Saturday, residents of Kaziba in the South Kivu province reported clashes between Congolese armed forces, supported by an allied militia, and M23.

M23 is one of about 100 armed groups vying for a foothold in mineral-rich eastern Congo near the border with Rwanda, in a conflict that has created one of the world’s most significant humanitarian crises. More than 7 million people have been displaced.

The rebels are supported by about 4,000 troops from neighbouring Rwanda, according to U.N. experts, and at times have vowed to march as far as Kinshasa.

In Feburary, the U.N. Human Rights Council launched a commission to investigate atrocities, including allegations of rape and killing akin to “summary executions” by both sides.

Conflict in eastern Congo is estimated to have killed 6 million people since the mid-1990s, in the wake of the Rwanda genocide. Some of the ethnic Hutu extremists responsible for the 1994 killing of an estimated 1 million of Rwanda’s minority ethnic Tutsis and Hutu moderates later fled across the border into eastern Congo, fueling the proxy fighting between rival militias aligned to the two governments.

Africa

Algeria to unveil military mobilisation bill amid regional tensions

Amid ongoing tension with neighbours Morocco and Mali, Algeria is to unveil a military mobilisation bill on Wednesday.

Adopted by the Council of Ministers earlier this month, the draft law signals a significant shift in the country’s security policies.

It comes as Algeria’s army chief of staff makes a series of trips to border areas to oversee military manoeuvres.

The draft bill lays the groundwork for a full-scale wartime mobilisation that would put civilians, the economy, and the country’s institutions under direct military command.

President Abdelmadjid Tebboune has described the proposed bill as a necessary legal framework to address any national crisis, not just war.

The unveiling of the text by the country’s minister of justice, comes after Algeria earlier this month said it had shot down a military drone near its border with Mali.

It was the first incident of its kind amid growing tensions between the two countries that each govern a vast portion of the Sahara.

Algier’s relations with former colonial power, France, have also deteriorated after Paris shifted its position to support Morocco’s autonomy plan for the disputed Western Sahara region.

The territory is claimed by the pro-independence Polisario Front, which receives support from Algeria.

The proposed military mobilisation bill has raised concerns among ordinary Algerians.

Africa

Thousands displaced by Sudan war return home from Egypt

Tens of thousands of Sudanese driven from their homes by conflict are now returning, despite war still raging in some parts of the country.

They set off on the journey, even though they don’t know what they’ll find in their homeland, wrecked and still embroiled in a two-year-old war.

But they are hoping for some stability after the military recaptured the capital Khartoum and other areas from its rival, the Rapid Support Forces.

Nearly 13 million people fled their homes, with some 4 million streaming into neighbouring countries and the rest sheltering elsewhere in Sudan.

A relatively small portion of the refugees are returning so far, but the numbers are accelerating.

Some 1.5 million Sudanese fled to Egypt during the war, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

In Cairo, travel agency coordinator Walid Abu el-Seid says there has been a noticeable uptick in travellers booking trips back to Sudan.

Hundreds of Sudanese take the two or three buses each day for southern Egypt, the first leg in the journey home.

According to the International Organization for Migration, some 123,000 Sudanese returned from Egypt since the start of the year, including nearly 50,000 so far in April, double the month before.

It estimates that some 400,000 internally displaced Sudanese have gone back to their homes in the Khartoum area, neighbouring Gezira province and southeast Sennar province.

But many of the returnees are finding their neighbourhoods shattered left shattered by fighting, often with no electricity and scarce food, water and services.

Still, Huzaifa Al-Mubarak was determined to go back.

About to board a bus in Egypt’s capital Cairo, he insisted that there were “no fears in Khartoum… It is safe and secure.”

The battle for power between the military and Rapid Support Forces caused one of the worst humanitarian crises in the world.

At least 20,000 people were killed, according to the United Nations, though the figure is likely higher.

Aid remains limited and the scale of needs far exceeds available resources, according to UNHCR officials.

-

Education2 days ago

Education2 days agoStudents and faculty demand Columbia University stand up to federal government

-

Europe2 days ago

Europe2 days agoAlexandra Fröhlich: Police launch murder investigation after bestselling novelist found dead on houseboat

-

Conflict Zones2 days ago

Conflict Zones2 days ago‘Traitors’: Hate-filled songs target Indian Muslims after Kashmir attack | Islamophobia News

-

Conflict Zones2 days ago

Conflict Zones2 days agoHezbollah leader says Lebanese gov’t must do more to end Israeli attacks | Hezbollah News

-

Middle East1 day ago

Middle East1 day agoI was forced to burn my books to survive in Gaza | Israel-Palestine conflict

-

Europe1 day ago

Europe1 day agoWhat caused the power outage in Spain and Portugal? Here’s what we know

-

Africa1 day ago

Africa1 day agoBomb Blast Kills 26 in Northeast Nigeria

-

Sports2 days ago

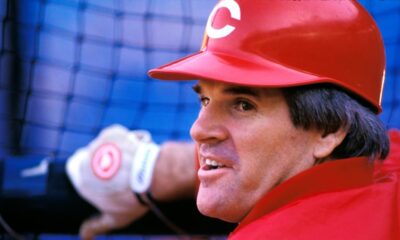

Sports2 days agoRob Manfred says he discussed Pete Rose’s status with Donald Trump and will rule on reinstatement