Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

CNN

—

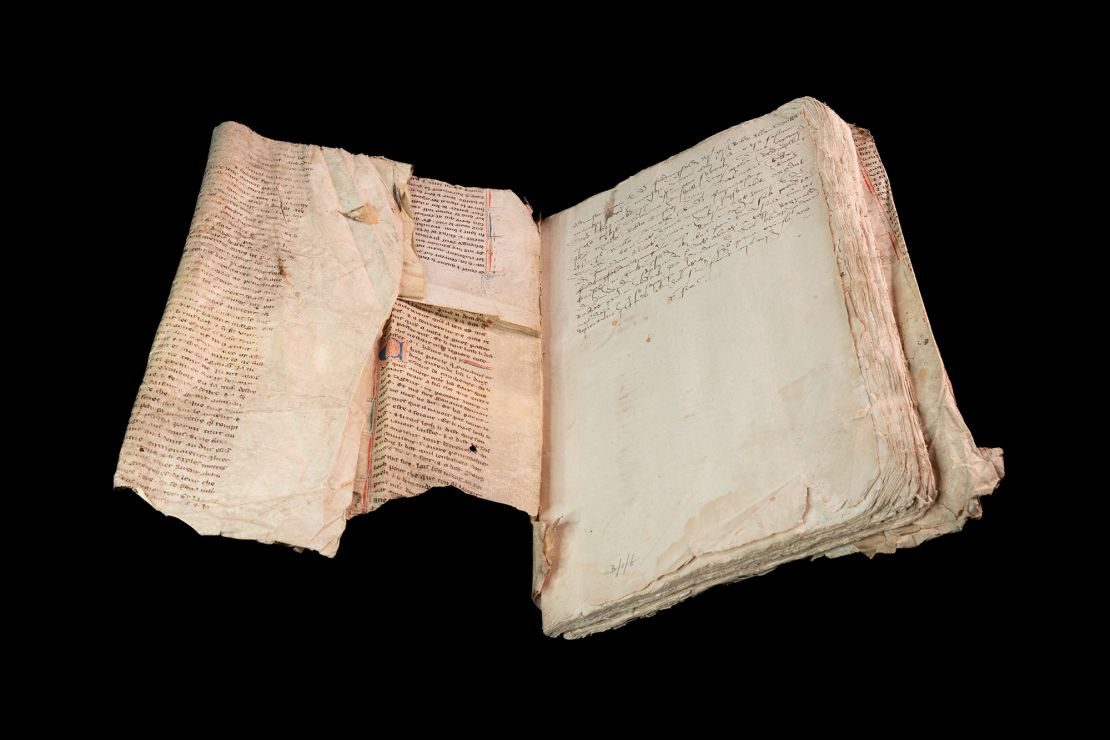

Researchers have found pages of a rare medieval manuscript masquerading as a cover and stitched into the binding of another book, according to experts at the Cambridge University Library in England. The fragment contains stories about Merlin and King Arthur.

The two pages are from a 13th century copy of the “Suite Vulgate du Merlin.” The manuscript, handwritten by a medieval scribe in Old French, served as the sequel to the legend of King Arthur. There are just over three dozen surviving copies of the sequel today.

Part of a series known as the Lancelot-Grail cycle, the Arthurian romance was popular among aristocrats and royalty, said Dr. Irène Fabry-Tehranchi, French specialist in collections and academic liaison at Cambridge University Library. The stories were either read aloud or performed by trouvères, or poets, who traveled from court to court, she said.

Rather than risk damaging the brittle pages by removing the stitches and unfolding them, a team of researchers were able to conduct imaging and computed tomography, or CT, scans to create a 3D model of the papers and virtually unfurl them to read the story.

Fabry-Tehranchi, one of the first to recognize the rarity of the manuscript, said finding it “is very much a once in a lifetime experience.”

The scans revealed book-binding techniques from the distant past and hidden details of the repurposed manuscript that could shed light on its origins.

“It’s not just about the text itself, but also about the material artefact,” Fabry-Tehranchi said in a statement. “The way it was reused tells us about archival practices in 16th-century England. It’s a piece of history in its own right.”

Former Cambridge archivist Sian Collins first spotted the manuscript fragment in 2019 while recataloging estate records from Huntingfield Manor, owned by the Vanneck family of Heveningham, in Suffolk, England. Serving as the cover for an archival property record, the pages previously had been recorded as a 14th century story of Sir Gawain.

But Collins, now the head of special collections and archives at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David, noticed that the text was written in Old French, the language used by aristocracy and England’s royal court after the Norman Conquest in 1066. She also saw names like Gawain and Excalibur within the text.

Collins and the other researchers were able to decipher text describing the fight and ultimate victory of Gawain, his brothers and his father King Loth versus the Saxon Kings Dodalis, Moydas, Oriancés, and Brandalus. The other page shared a scene from King Arthur’s court in which Merlin appears disguised as a dashing harpist, according to a translation provided by the researchers:

“While they were rejoicing in the feast, and Kay the seneschal (steward) brought the first dish to King Arthur and Queen Guinevere, there arrived the most handsome man ever seen in Christian lands. He was wearing a silk tunic girded by a silk harness woven with gold and precious stones which glittered with such brightness that it illuminated the whole room.”

Both scenes are part of the “Suite Vulgate du Merlin” that was originally written in 1230, about 30 years after “Merlin,” which tells the origin stories of Merlin and King Arthur and ends with Arthur’s coronation.

“(The sequel) tells us about the early reign of Arthur: he faces a rebellion of British barons who question his legitimacy and has to fight external invaders, the Saxons,” Fabry-Tehranchi said in an email. “All along, Arthur is supported by Merlin who advises him strategically and helps him on the battlefield. Sometimes Merlin changes shape to impress and entertain his interlocutors.”

The pages had been torn, folded and sewn, making it impossible to decipher the text or determine when it was written. A team of Cambridge experts came together to conduct a detailed set of analyses.

After analyzing the pages, the researchers believe the manuscript, bearing telltale decorative initials in red and blue, was written between 1275 and 1315 in northern France, then later imported to England.

They think it was a short version of the “Suite Vulgate du Merlin.” Because each copy was individually written by hand by medieval scribes, a process that could take months, there are distinguishing typos, such as “Dorilas” instead of “Dodalis” for one of the Saxon kings’ names.

“Each medieval copy of a text is unique: it presents lots of variations because the written language was much more fluid and less codified than nowadays,” Fabry-Tehranchi said. “Grammatical and spelling rules were established much later.”

But it was common to discard and repurpose old medieval manuscripts by the end of the 16th century as printing became popular and the true value of the pages became their sturdy parchment that could be used for covers, Fabry-Tehranchi said.

“It had probably become harder to decipher and understand Old French, and more up to date English versions of the Arthurian romances, such as (Sir Thomas) Malory’s ‘Morte D’Arthur’ were now available for readers in England,” Fabry-Tehranchi said.

The updated Arthurian texts were edited to be more modern and easier to read, said Dr. Laura Campbell, associate professor in the School of Modern Languages and Cultures at Durham University in Durham, England, and president of the British branch of The International Arthurian Society. Campbell was not involved in the project, but has previously worked on the discovery of another manuscript known as the Bristol Merlin.

“This suggests that the style and language of these 13th-century French stories were hitting a point where they badly needed an update to appeal to new generations of readers, and this purpose was being fulfilled by in print as opposed to in manuscript form,” Campbell said. “This is something that I think is really important about the Arthurian legend — it has such appeal and longevity because it’s a timeless story that’s open to being constantly updated and adapted to suit the tastes of its readers.”

Researchers captured the documents across wavelengths of light, including ultraviolet and infrared, to improve the readability of the text and uncover hidden details, as well as annotations in the margins. The team carried out CT scanning with an X-ray scanner to virtually peer through the parchment layers and create a 3D model of the manuscript fragment, revealing how the pages had been stitched together to form a cover.

The CT scans showed there was likely once a leather band around the book to hold it all in place, which rubbed off some of the text. Twisted straps of parchment, called tackets, along with thread reinforced the binding.

“A series of specialised photographic equipment such as a probe lens as well as simple accessories such as mirrors were used to photograph otherwise inaccessible parts of the manuscript,” said Amélie Deblauwe, a photographer at Cambridge University Library’s Cultural Heritage Imaging Laboratory.

The research team digitally assembled hundreds of images to create a virtual copy of the pages.

“The creation of these digital outputs including the virtual unfolding, traditional photography, and (multispectral imaging) all contribute to the preservation of the manuscript in its reused form, while revealing as much of the original contents as possible,” Deblauwe said.

The researchers believe the methodology they developed for this project can be applied to other fragile manuscripts, especially those repurposed for other uses over time, to provide a nondestructive type of analysis. The team plans to share the methodology in an upcoming research paper.