CNN

—

The NFL draft is broadcast live on television every year as millions tune in and hundreds of thousands more attend in person to revel in the hoopla of it all.

It’s a far cry from the event’s humble beginnings, when the player picked first didn’t even know it was happening and soon walked away from the game without ever earning a cent.

There are no tackles or touchdowns, but the draft has become one of the biggest sports events of the year, because the fans know that a three-day event in April could impact the fortunes of their teams for years to come. Two-hundred-fifty-seven players will be drafted this week in Green Bay, Wisconsin, and anyone chosen in the first round – which begins at 8 p.m. ET on Thursday – will be set for life with guaranteed multi-million-dollar contracts. It was all very different in the first year of the draft back in 1936 when just 81 players were selected through nine rounds in the inaugural draft.

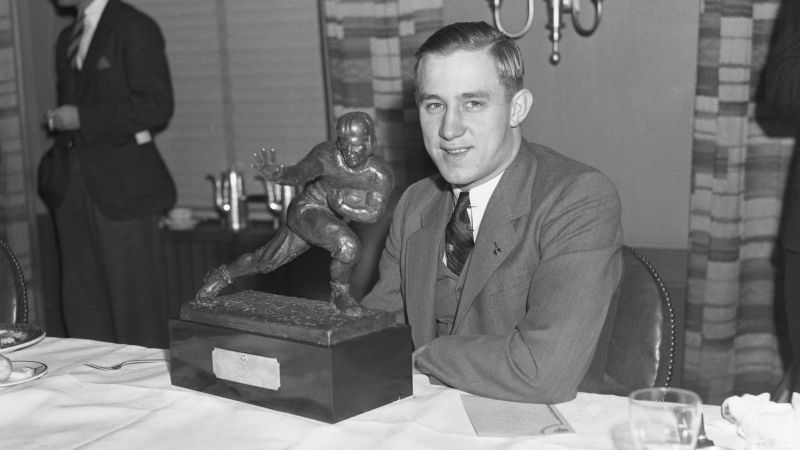

There was little doubt that University of Chicago halfback Jay Berwanger would go first that year. At 6-foot tall and 195 pounds, the standout player of his class had just received the first ever Heisman Trophy and been named as the Chicago Tribune’s Big 10 player of the year.

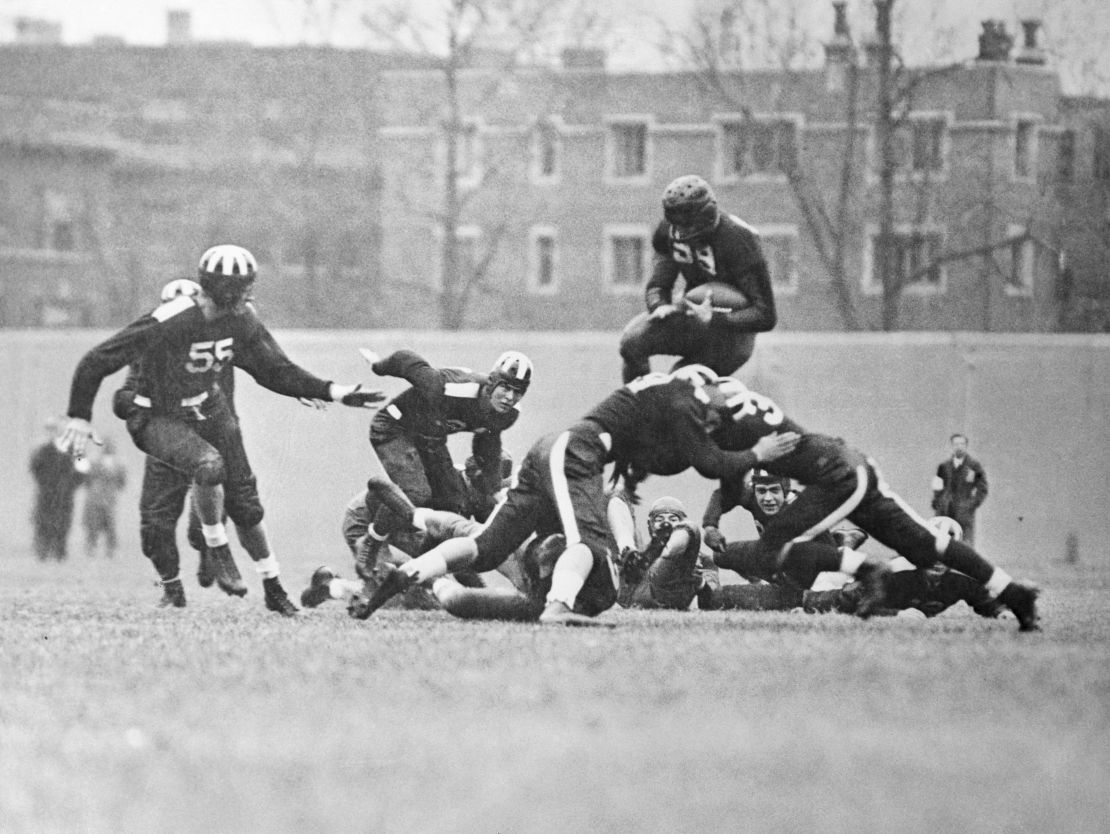

“He played offense, defense and special teams for Chicago,” explained Landon Bundy, the school’s director of sports information and promotions, to CNN. “He pretty much never came off the field and he played every single position there was on defense.”

Bundy said that Berwanger was also the team’s kicker, so he’d often score a touchdown and then kick the extra point himself.

“In his Heisman Trophy campaign, it looks like he passed for 405 yards and ran for 577 yards,” Bundy said. “He was the kickoff returner, and he scored six touchdowns, kicking five of the extra points. Basically, he did it all.”

“You can say anything superlative about him and I’ll double it,” said his coach Clark Shaughnessy to the Chicago Tribune in 1935.

Among his many nicknames, Berwanger was known as “The Man in the Iron Mask,” a reference to the faceguard he wore to protect his twice-broken nose. For more reasons than one, he was hard to forget – the Chicago Tribune polled all the opposing players in Berwanger’s senior season and 104 of the 107 participants concluded that he was the best halfback they’d ever seen.

Even Gerald Ford, a future president who won back-to-back national championships with Michigan, would attest to Berwanger’s brilliance and he carried a permanent scar under his left eye to prove it.

The New York Times quoted Ford in 2002, “When I tackled Jay one time, his heel hit my cheekbone and opened it up three inches,” he said. Ford has described Berwanger as “one of the greatest athletes I’ve known.”

In November 1935, the Downtown Athletic Club in New York recognized Berwanger’s impact on the college game by making him the inaugural recipient of a new trophy given to the “most valuable player east of the Mississippi.” The following year it was renamed after club’s late athletic director, John Heisman.

On hearing news of his accolade via a telegram, Berwanger didn’t quite know what to make of it. Speaking about the honor a half-century later he said that it wasn’t really a big deal at the time.

“No one at school said anything to me about winning it other than a few congratulations. I was more excited about the trip (to New York) than the trophy because it was my first flight,” he said.

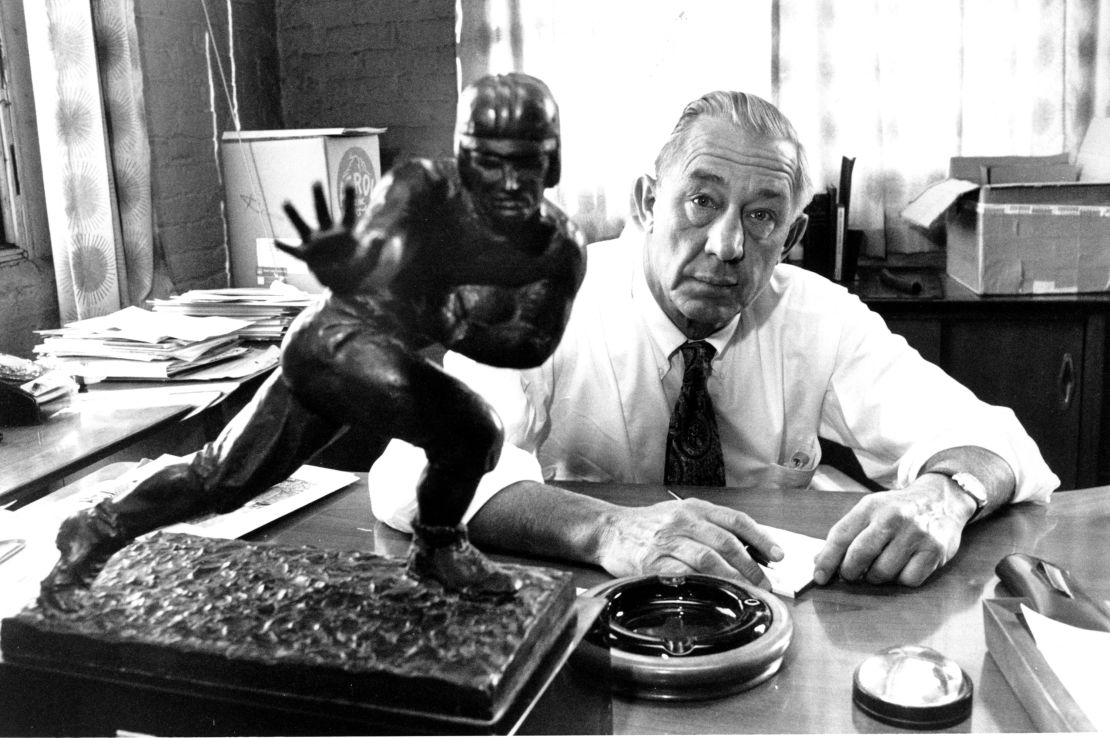

Indeed, Berwanger didn’t have much use for the trophy once it was in his possession, which was described as being too wide for a mantlepiece and too large for a coffee table. According to the UChicago magazine, the stiff arm of the player depicted in the trophy spent many years propping the door open at his Aunt Gussie’s house.

Three months later, the NFL held its first formalized draft and it was much different than the razzmatazz of the modern day. The Hartford Courant described it as “no gala, more like a penny-ante poker game. Nine cigar-puffing, mogul wannabees, some of whom were paying their players with IOUs, stubbornly trying to salvage their dream of professional football.”

Berwanger told the Courant in 1994 that he was oblivious to the draft at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel in Philadelphia.

“I found out I was drafted by reading it in the newspaper,” he said, “I didn’t even know the draft was going on.”

Philadelphia Eagles owner Bert Bell had persuaded his peers to formalize a draft in order to cease the expensive and “self-defeating” bidding wars for college players and he’d proposed that teams should choose players in reverse order from the previous season’s standings. That meant the worst team, Bell’s own 2-9 Eagles, went first and chose Berwanger, quickly dealing his rights to the Chicago Bears. The Eagles didn’t think they’d be able to afford Berwanger’s salary demands, and the Bears owner and coach George Halas soon realized he didn’t have enough money, either.

According to the Courant, the two met in the lobby of a downtown hotel in Chicago.

“He asked what I wanted,” Berwanger recalled, “and I had my tongue in my cheek. I told him, $25,000 for two years. He looked at my date and said, `Nice to have met you; have a nice time tonight.’ And that was the end of it.”

As Brian E Cooper, author of “First Heisman: The Life of Jay Berwanger” described it to UChicago Magazine, the player had made the Bears an offer they simply couldn’t accept.

“Jay basically signaled to Halas, by making an extremely high salary ‘demand,’ that he wasn’t really that interested in pro football,” Cooper said.

In his obituary in 2002, the Los Angeles Times quoted Berwanger, who had said, “There was no money in pro football then, that was during the Great Depression. I thought I’d have a better future by using my education rather than my football skills.”

Having snubbed a career as a professional football player, Berwanger considered competing in the decathlon at the Berlin Olympics that summer, but he chose instead to finish his studies, and he went to work as a foam rubber-salesman. In World War Two, he rose to the rank of lieutenant commander as a Navy flight instructor, and after the war he founded a company that made plastic and sponge-rubber strips for cars and farm machinery. According to the New York Times, Jay Berwanger Inc. was grossing $30 million a year when he sold it in 1992.

Berwanger isn’t the only player to be drafted first in the NFL and not play a game; tragically, the Heisman Trophy’s first black recipient, Ernie Davis, was picked first in 1962 but died of leukemia at the age of 23 and never played for the Cleveland Browns.

And although Berwanger never played in the NFL, his name still carries a unique distinction within a league that would become the most lucrative in all of sport. He was the very first pick in the very first draft, but his timing was just a little off. Before his death at the age of 88 in 2002, Berwanger noted that if he’d been drafted even just a few years later, then he would surely have turned professional. And nobody can deny that he was an original.

“I still think of myself as the first, kind of like being George Washington,” Berwanger once said.