Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

CNN

—

A piece of a Soviet vehicle that malfunctioned en route to Venus more than 50 years ago is due to crash back to Earth as soon as this week.

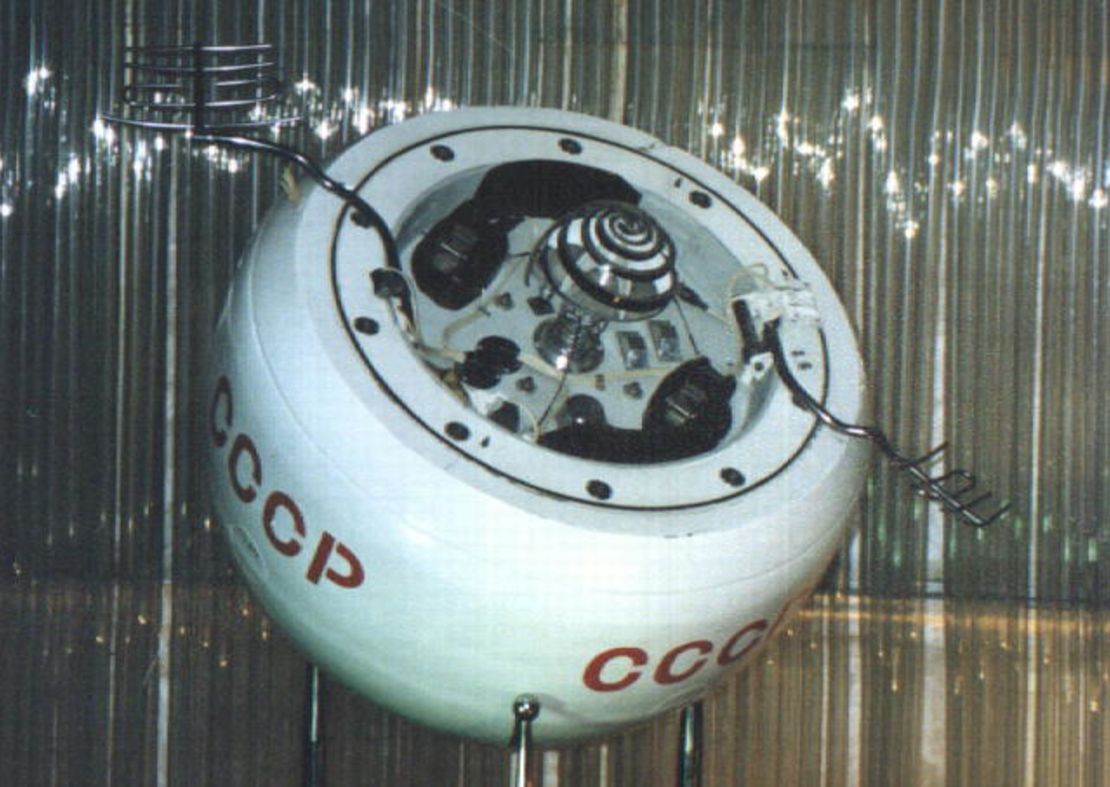

Much about the piece of space debris, called Cosmos 482 (also spelled Kosmos 482), is unknown.

Though most projections estimate that the object will reenter the atmosphere around May 10, unknowns about its exact shape and size — as well as the unpredictability of space weather — make some degree of uncertainty inevitable.

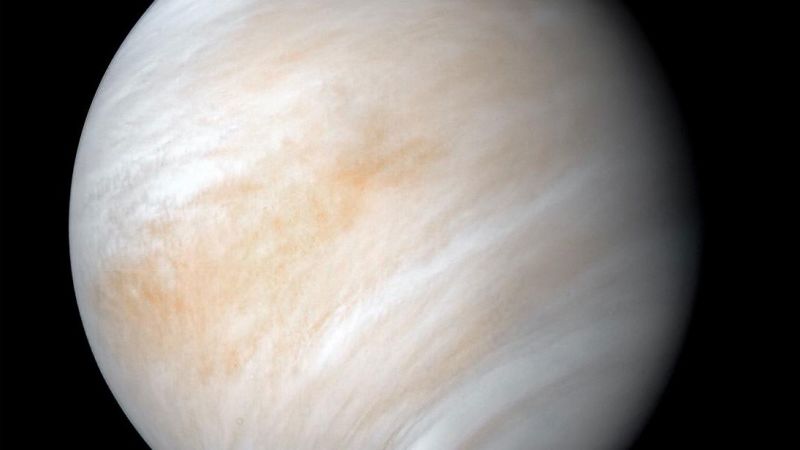

It’s also unclear which portion of the vehicle is set to reenter, though researchers believe it to be the probe, or “entry capsule,” which was designed to survive the extreme temperature and pressure of landing on Venus — which has an atmosphere 90 times more dense than Earth’s. That means it could survive its unexpected trip back home, posing a small but non-zero risk to people on the ground.

While space junk and meteors routinely veer toward a crash-landing on Earth, most of the objects disintegrate as they’re torn apart due to friction and pressure as they hit Earth’s thick atmosphere while traveling thousands of miles per hour.

But if the Cosmos 482 object is indeed a Soviet reentry capsule, it would be equipped with a substantial heat shield, meaning it “might well survive Earth atmosphere entry and hit the ground,” according to Dr. Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist and astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who shared his predictions about Cosmos 482 on his website.

The risk of the object hitting people on the ground is likely minimal, and there’s “no need for major concern,” McDowell wrote, “but you wouldn’t want it bashing you on the head.”

The Soviet Space Research Institute, or IKI, was formed in the mid-1960s amid the 20th-century space race, which pitted the Soviet Union against its chief space-exploring competitor, the United States.

The IKI’s Venera program sent a series of probes toward Venus in the 1970s and ‘80s, with several surviving the trip and beaming data and images back to Earth before ceasing operations.

Two spacecraft under that program, V-71 No. 670 and V-71 No. 671, launched in 1972, according to McDowell. But only one made a successful voyage to Venus: V-71 No. 670 operated for about 50 minutes on the planet’s surface.

V-71 No. 671 did not. A rocket carried the Venera spacecraft into a “parking orbit” around Earth. However, the vehicle then failed to put itself on a Venus transfer trajectory, leaving it stranded closer to home, according to NASA.

Beginning in the 1960s, Soviet vehicles left in Earth’s orbit were each given the Cosmos name and a numerical designation for tracking purposes, according to NASA.

Several pieces of debris were created from V-71 No. 671’s failure. At least two have already fallen out of orbit. But researchers believe the one set to plummet back to our planet this week is the cylindrical entry capsule — or Cosmos 482 — because of the way the vehicle has behaved in orbit.

“It is quite dense, whatever it is, because it had a very low point in its orbit, yet it didn’t decay for decades,” said Marlon Sorge, a space debris expert with the federally funded research group, The Aerospace Corporation. “So it’s clearly bowling ball-ish.”

And though the Venus probe was equipped with a parachute, the vehicle has been out of service in the harsh environment of space for the past few decades. That means it’s highly unlikely that a parachute could deploy at the right time or serve to slow down the vehicle’s descent, Sorge and Langbroek told CNN.

The chances of Cosmos 482 causing deadly damage is are roughly 1 in 25,000, according to The Aerospace Corporation’s calculations, Sorge said.

That’s a much lower risk than some other pieces of space debris. At least a few defunct rocket parts reenter Earth’s atmosphere each year, Sorge noted, and many have carried higher odds of catastrophe.

But if the Cosmos 482 object does hit the ground, it is likely to land between 52 degrees North and 52 South latitudes, Langbroek said via email.

“That area encompasses several prominent landmasses and countries: the whole of Africa, South America, Australia, the USA, parts of Canada, parts of Europe, and parts of Asia,” Langbroek said.

“But as 70% of our planet is water, chances are good that it will end up in an Ocean somewhere,” Langbroek said via email. “Yes, there is a risk, but it is small. You have a larger risk of being hit by lightning once in your lifetime.”

Sorge emphasized that if Cosmos 482 hits dry land, it’s crucial that bystanders do not attempt to touch the debris. The old spacecraft could leak dangerous fuels or pose other risks to people and property.

“Contact the authorities,” Sorge urged. “Please don’t mess with it.”

Parker Wishik, a spokesperson for the Aerospace Corporation, added that under the 1967 Outer Space Treaty — which remains the primary document outlining international space law — Russia would maintain ownership of any surviving debris and may seek to recover it after landing.

And while the global space community has taken steps in recent years to ensure that fewer spacecraft make uncontrolled crash-landings back on Earth, the Cosmos 482 vehicle highlights the importance of continuing those efforts, Wishik added.

“What goes up must come down,” he said. “We’re here talking about it more than 50 years later, which is another proof point for the importance of debris mitigation and making sure we’re having that that dialogue (as a space community) because what you put up in space today might affect us for decades to come.”