Conflict Zones

Yemen’s Houthis launch missiles at Israel, army says it intercepts | Houthis News

The group says it attacked an Israeli military base with a hypersonic missile.

Yemen’s Houthis have claimed responsibility for launching two missiles towards northern Israel, targeting the Ramat David military airbase and the Tel Aviv area, as the group continues its military pressure in solidarity with Palestinians under Israeli fire.

The Israeli military said on Friday it intercepted the first missile and launched another interceptor at the second, which was also fired from Yemen.

Alarms were triggered in several locations, though authorities reported no casualties or damage. The military added that the outcome of the second interception was still under review.

Yahya Saree, spokesperson for the Houthis – also known as Ansar Allah – confirmed the group had carried a “military operation” against a key Israeli military target.

Saree said hypersonic missiles were used and had successfully hit their intended destination.

The Israeli army responded that “interception attempts were made” without providing further details.

The Houthi group has repeatedly said its attacks on Israel as well as United States and British ships in the Red Sea and Bab al-Mandeb Strait will only cease if Israel agrees to a permanent Gaza truce.

The Houthis did not carry out attacks during the Gaza ceasefire earlier this year until Israel blocked all aid into the besieged enclave in early March and followed that with a full resumption of the war.

Growing civilian death toll

The attacks come as the US escalates its military operations in Yemen.

Since March, the US has launched large-scale attacks not only on infrastructure but increasingly on individuals linked to the Houthi leadership.

Civilian casualties are mounting, with UK-based monitor Airwars estimating between 27 and 55 civilians were killed in March alone, and suggesting April’s toll is even higher.

One of the deadliest US strikes in April hit Ras Isa port in Hodeidah, killing at least 80 people and wounding more than 150.

On Monday at least 68 people were killed in the overnight strike on detained African migrants, and eight people were killed around the capital, Houthi media reported.

Rights advocates have been alarmed about the growing civilian death toll. Three US Democratic senators recently wrote to Pentagon chief Pete Hegseth, demanding an accounting for civilian lives lost.

“Strikes pose a growing risk to the civilian population in Yemen,” United Nations spokesperson Stephane Dujarric said on Monday. “We continue to call on all parties to uphold their obligations under international humanitarian law, including the protection of civilians.”

Conflict Zones

‘Don’t see a major war with India, but have to be ready’: Pakistan ex-NSA | Border Disputes News

Islamabad, Pakistan – Eleven days after gunmen shot 26 people dead in the scenic valley of Baisaran in Indian-administered Kashmir’s Pahalgam, India and Pakistan stand on the brink of a military standoff.

The nuclear-armed neighbours have each announced a series of tit-for-tat steps against the other since the attack on April 22, which India has implicitly blamed Pakistan for, even as Islamabad has denied any role in the killings.

India has suspended its participation in the Indus Waters Treaty that enforces a water-sharing mechanism Pakistan depends on. Pakistan has threatened to walk away from the 1972 Simla Agreement that committed both nations to recognising a previous ceasefire line as a Line of Control (LoC) – a de-facto border – between them in Kashmir, a disputed region that they each partly control but that they both claim in its entirety. Both nations have also expelled each other’s citizens and scaled back their diplomatic missions.

Despite a ceasefire agreement being in place since 2021, the current escalation is the most serious since 2019, when India launched air strikes on Pakistani soil following an attack on Indian soldiers in Pulwama, in Indian-administered Kashmir, that killed 40 troops. In recent days, they have traded fire across the LoC.

And the region is now on edge, amid growing expectations that India might launch a military operation against Pakistan this time too.

Yet, both countries have also engaged their diplomatic partners. On Wednesday, United States Secretary of State Marco Rubio called Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif and Indian Foreign Minister S Jaishankar, urging both sides to find a path to de-escalation. US Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth called his Indian counterpart, Rajnath Singh, on Thursday to condemn the attack and offered “strong support” to India.

Sharif met envoys from China, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, three of Pakistan’s closest allies, to seek their support, and urged the ambassadors of the two Gulf nations to “impress upon India to de-escalate and defuse tensions”.

To understand how Pakistani strategists who have worked on ties with India view what might happen next, Al Jazeera spoke with Moeed Yusuf, who served as Pakistan’s national security adviser (NSA) between May 2021 and April 2022 under former Prime Minister Imran Khan.

Prior to his role as NSA, Yusuf also worked as a special adviser to Khan on matters related to national security starting in December 2019, four months after the Indian government, under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, revoked the special status of Indian-administered Kashmir.

Based in Lahore, Yusuf is currently the vice chancellor of a private university and has authored and edited several books on South Asia and regional security. His most recent book, Brokering Peace in Nuclear Environments: US Crisis Management in South Asia, was published in 2018.

Al Jazeera: How do you assess moves made by both sides so far in the crisis?

Moeed Yusuf: India and Pakistan have for long struggled in terms of crisis management. They don’t have a bilateral crisis management mechanism, which is the fundamental concern.

The number one crisis management tool used by both sides has been the reliance on third parties, with the idea being that they would try and restrain them both and help de-escalate the crisis.

This time, I feel the problem India has run into is that they followed the old playbook, but the leader of the most important third party, the United States, didn’t show up to support India.

It appears that they have so far taken a neutral and a hands-off position, as indicated by President Donald Trump few days ago. (Trump said that he knew the leaders of both India and Pakistan, and believed that they could resolve the crisis on their own.)

Pakistan’s response is directly linked to the Indian response, and that is historically how it has been, with both countries going tit-for-tat with each other. This time too, a number of punitive steps have been announced.

The problem is that these are easy to set into motion but very difficult to reverse, even when things get better, and they may wish to do so.

Unfortunately, in every crisis between them, the retaliatory steps are becoming more and more substantive, as in this case, India has decided to hold Indus Water Treaty in abeyance, which is illegal as the treaty provides no such provision.

Al Jazeera: Do you believe a strike is imminent and if both sides are indicating preparedness for a showdown?

Yusuf: In such moments, it is impossible to say. Action from India remains plausible and possible, but the window where imminence was a real concern has passed.

What usually happens in crises is that countries pick up troop or logistics movements, or their allies inform them, or they rely on ground intelligence to determine what might happen. Sometimes, these can be misread and can lead the offensive side to see an opportunity to act where none exists or the defensive side to believe an attack may be coming when it isn’t the case.

Pakistan naturally has to show commitment to prepare for any eventuality. You don’t know what will come next, so you have to be ready.

Having said that, I don’t think we are going to see a major war, but in these circumstances, you can never predict, and one little misunderstanding or miscalculation can lead to something major.

Al Jazeera: How do you see the role of third parties such as the US, China and Gulf States in this crisis, and how would you compare it with previous instances?

Yusuf: My last book, Brokering Peace (2018) was on the third-party management in Pakistan-India context, and this is such a vital element for both as they have internalised and built it into their calculus that a third-party country will inevitably come in.

The idea is that a third-party mediator will step in, and the two nations will agree to stop because that is what they really want, instead of escalating further.

And the leader of the pack of third-party countries is the United States since the Kargil war of 1999. (Pakistani forces crossed the LoC to try to take control of strategic heights in Ladakh’s Kargil, but India eventually managed to take back the territory. Then-US President Bill Clinton is credited with helping end that conflict.)

Everybody else, including China, ultimately backs the US position, which prioritises immediate de-escalation above all else during the crisis.

This changed somewhat in the 2016 surgical strikes and 2019 Pulwama crisis when the US leaned heavily on India’s side, perhaps unwittingly even emboldening them to act in 2019.

(In 2016, Indian troops launched a cross-border “surgical strike” that New Delhi said targeted armed fighters planning to attack India, after gunmen killed 19 Indian soldiers in an attack on an army base in Uri, Indian-administered Kashmir. Three years later, Indian fighter jets bombed what New Delhi said were bases of “terrorists” in Balakot, in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, after the attack on the Indian military convoy in which 40 soldiers were killed. India and Pakistan then engaged in an aerial dogfight, and an Indian pilot was captured and subsequently returned.)

However, this time, you have a president in the White House who turned around and told both Pakistan and India to figure it out themselves.

This, I think, has hurt India more than Pakistan, because for Pakistan, they had discounted the possibility of significant US support in recent years, thinking they have gotten too close to India due to their strategic relationship.

But India would have been hoping for the Americans to put their foot down and pressure Pakistan, which did not exactly materialise. Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s phone call again is playing down the middle, where they are telling both the countries to get out of war.

So, what they have done has, oddly enough, still played a role in holding India back so far, since India didn’t (so far) feel as emboldened to take action as they may have during Pulwama in 2019.

Gulf countries have played a more active role than before. China, too, has made a statement of restraint.

Al Jazeera: How has Pakistan’s relationship with India evolved in recent years?

Yusuf: There has been a sea change in the relationship between the two countries. When I was in office, despite serious problems and India’s unilateral moves in Kashmir in 2019, we saw a ceasefire agreement on the Line of Control as well as back-channel talks.

We have tried to move ahead and reduce India’s incentive to destabilise Pakistan, but I think India has lost that opportunity due to its own intransigence, hubris and an ideological bent that continues to force them to demean and threaten Pakistan.

That has led to a change in Pakistan as well, where the leadership is now convinced that the policy of restraint did not deliver, and India has misused and abused Pakistan’s offers for dialogue.

The view now is that if India doesn’t want to talk, Pakistan shouldn’t be pleading either. If India does reach out, we will likely respond, but there isn’t any desperation in Pakistan at all.

This is not a good place to be for either country. I have long believed and argued that ultimately for Pakistan to get to where we want to go economically, and for India to get to where it says it wants to go regionally, it cannot happen unless both improve their relationship. For now, though, with the current Indian attitude, unfortunately, I see little hope.

Al Jazeera: Do you anticipate any direct India-Pakistan talks at any level during or after this crisis?

Yes – I don’t know when it will be, or who will it be through or with, but I think one of the key lessons Indians could probably walk away with once all this is over is that attempting to isolate Pakistan isn’t working.

Indus Water Treaty in abeyance? Simla Agreement’s potential suspension? These are major decisions, and the two countries will need to talk to sort these out, and I think at some point in future they will engage.

But I also don’t think that Pakistan will make a move towards rapprochement, as we have offered opportunities for dialogues so many times recently to no avail. As I said, the mood in Pakistan has also firmed up on this question.

Ultimately, the Indians need to basically decide if they want to talk or not. If they come forth, I think Pakistan will still respond positively to it.

*This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Conflict Zones

‘Everyone lives in fear’: Voices of Kashmir after deadly Pahalgam attack | Armed Groups

Srinagar, Indian-administered Kashmir — India and Pakistan are on edge, amid speculation that New Delhi might launch a military operation against its western neighbour days after the deadly attack on tourists in Pahalgam in Indian-administered Kashmir.

On the afternoon of April 22, suspected rebels emerged from the forests into a picturesque meadow in Pahalgam accessible only by foot or horseback, and opened fire on male tourists. They killed 25 tourists and a local Kashmiri pony rider.

The worst such attack in Kashmir in a quarter-century set off a spiral of tit-for-tat steps by India and Pakistan that have brought the nuclear-armed neighbours to the brink of military conflict.

Yet while India blames Pakistan for the attack, and Islamabad accuses New Delhi of not sharing any evidence to back its claims, Kashmir is facing the brunt of their tensions.

India has responded to the Pahalgam attack with a spree of detentions of people suspected of supporting secessionist groups; and raids and demolitions of the homes of rebels, in the part of Kashmir it administers. It has also temporarily shut down tourism in parts of the Kashmir valley. It is also expelling Pakistanis living in India and Indian-administered Kashmir – including the families of former rebels New Delhi had previously invited as a part of a rehabilitation programme.

Meanwhile, dozens of Kashmiris in cities across India have reported facing harassment, physical assault and threats to leave.

Al Jazeera spoke to people living in the region about how their lives have been affected by the Pahalgam attack.

Ashiq Nabi, 35, adventure tour operator

I was in Pahalgam when the attack took place. It was shocking for all of us.

As an architect and tourism planner focused on developing adventure tourism in Kashmir, I experienced the immediate fallout of the incident.

The government’s decision to suspend all trekking activities and close 48 tourist destinations following the attack has directly impacted my work. The months of planning, coordination with local partners and scheduled expeditions were brought to an abrupt halt.

The attack led to mass cancellations, financial losses, and the dismissal of local guides, porters, and service staff – many of whom rely entirely on seasonal tourism for income.

The impact extended beyond businesses; it shook the confidence of tourists and disrupted the livelihoods of hundreds of people across the tourism value chain.

My years of work to brand Kashmir as a safe, adventure-friendly destination have been lost abruptly. My work has taken a significant hit, but I hope that things will improve, tourists will come back and the sector will revive.

I am very stressed about my livelihood right now but there is no option but to hope.

Rameez Ahmad, 40, a tourist taxi driver

What happened in Pahalgam should never have happened.

Incidents like that don’t just create panic, they destroy our only source of livelihood. Since that day, the number of tourists has dropped so badly that I have spent these days without a single ride.

I sit idle, waiting near taxi stands or at home, hoping someone might call me but the phone just does not ring any more.

Since March, this year had started with some hope. Bookings were picking up, and it felt like we might finally see a good season after years of struggle. But now everything has come crashing down.

I fear that if this continues, people like me, who have no government job, no land, no business, will be left penniless.

We survive on tourism and this incident has been a big setback as I am left with no other option. I don’t have savings to fall back on. I have a family to support, children to educate and loans to repay. When tourists don’t come, it’s not just a bad day at work, it’s a question of how we will eat tomorrow.

*Amir Ahmad 26, a job aspirant

I was staying in a rented room in Srinagar [Indian-administered Kashmir’s main city] when the Pahalgam incident took place. Following reports of youth being picked up across Kashmir, I was urgently called back home [in central Kashmir’s Ganderbal district].

A few months earlier, I was summoned to the local police station over a social media post which they did not like. I was let off with a warning and sent home. Since returning from my rented accommodation, I have been confined to my house. My parents don’t allow me to step outside. Every time I get a call, I feel a wave of anxiety, fearing it might be the police.

My mother was scheduled to travel to Delhi in a few days for open-heart surgery, but now she is too afraid to go. One of my friends who is a student recently returned and warned us that it is extremely dangerous to travel under the current circumstances. He was studying in Punjab and had to rush home after attacks on Kashmiri students.

Our lives have become so uncertain that we do not know whether we should worry about two meals, our job, our education, our homes being demolished or the political uncertainty that is shaping up.

Kashmir might be a wonderland, a mini-Switzerland or a paradise for others, but for us, it is an open prison. Everyone lives in fear. What future do we have?

Ajmal, 21, migrant worker from Bihar

My sister has been living in Kashmir with her husband and children for over a decade.

A few years ago, she brought me here as well. She had never once complained about facing any harm. In fact, she would always speak highly of the locals and their warmth. That is what encouraged me to come and try building a life here, too. I sell pani puri [a popular street snack in South Asia] on a cart and earn my livelihood. The weather is also good here.

When the attack on tourists happened, it did create fear on the first day. We were very scared not knowing what would happen. But things are returning to normal slowly and people are gradually returning to their daily routine. I continue to run my stall and even close it late in the evening without much worry. We are feeling safe so far.

The atmosphere here, at least for now, doesn’t feel threatening to outsiders.

*Safiya Jan, 40

I am originally from Karachi [in Pakistan]. I came to Kashmir in 2014 under the rehabilitation policy announced by the [Indian] government for the families of the former rebels who had gone to Pakistan but gave up guns and settled there.

After marrying my husband, who is from Baramulla in north Kashmir, I came to Kashmir. For the past decade, I have been living here with him and our two daughters. This is our home now.

When I hear today that Pakistani residents are being sent back, I get anxious. My heart breaks. I don’t want to go back. How can I leave my husband and children behind and return alone? I would rather die than be separated from my family. I beg the government, with folded hands, please don’t send us away.

My daughters are studying here. We have built a life in Kashmir, brick by brick, year after year. We are not a threat to anyone. All we want is to live in peace, together as a family.

If I am sent back, it is like cutting an arm or leg from the body, who on Earth would do that?

*The names of Amir and Safiya have been changed at their request for their safety.

Conflict Zones

Pahalgam attack: A simple guide to the Kashmir conflict | Border Disputes News

Islamabad, Pakistan – Pakistan and India continue to engage in war rhetoric and have exchanged fire across the Line of Control (LoC), the de facto border in Kashmir, days after the Pahalgam attack, in which 26 civilians were killed in Indian-administered Kashmir on April 22.

Since then, senior members of Pakistan’s government and military officials have held multiple news conferences in which they have claimed to have “credible information” that an Indian military response is imminent.

This is not the first time South Asia’s two largest countries – which have a combined population of more than 1.6 billion people, about one-fifth of the world’s population – have found themselves under the shadow of potential war.

At the heart of their longstanding animosity lies the status of the picturesque valley of Kashmir, over which India and Pakistan have fought three of their four previous wars. Since gaining independence from British rule in 1947, both countries have controlled parts of Kashmir – with China controlling another part of it – but continue to claim it in full.

So what is the Kashmir conflict all about, and why do India and Pakistan continue to fight over it nearly eight decades after independence?

What are the latest tensions about?

India has implied it believes Pakistan may have indirectly supported the Pahalgam attack – a claim Pakistan strongly denies. Both countries have engaged in tit-for-tat diplomatic swipes at each other, including cancelling visas for each other’s citizens and recalling diplomatic staff.

India has suspended its participation in the Indus Waters Treaty, a water use and distribution agreement with Pakistan. Pakistan has in turn threatened to walk away from the Simla Agreement, which was signed in July 1972, seven months after Pakistan decisively lost the 1971 war that led to the creation of Bangladesh. The Simla Agreement has since formed the bedrock of India-Pakistan relations. It governs the LoC and outlines a commitment to resolve disputes through peaceful means.

On Wednesday, United States Secretary of State Marco Rubio called Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif and Indian External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar to urge both countries to work together to “de-escalate tensions and maintain peace and security in South Asia”.

US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth also called Indian Defence Minister Rajnath Singh on Thursday to condemn the attack. “I offered my strong support. We stand with India and its great people,” Hegseth wrote on X.

What lies at the heart of the Kashmir conflict?

Situated in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent, the region spans 222,200 square kilometres (85,800sq miles) with about four million people living in Pakistan-administered Kashmir and 13 million in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir.

The population is overwhelmingly Muslim. Pakistan controls the northern and western portions, namely Azad Kashmir, Gilgit and Baltistan, while India controls the southern and southeastern parts, including the Kashmir Valley and its biggest city, Srinagar, as well as Jammu and Ladakh.

The end of British colonial rule and the partition of British India in August 1947 led to the creation of Muslim-majority Pakistan and Hindu-majority India.

At the time, princely states like Jammu and Kashmir were given the option to accede to either country. With a nearly 75 percent Muslim population, many in Pakistan believed the region would naturally join that country. After all, Pakistan under Muhammad Ali Jinnah was created as a homeland for Muslims, even though a majority of Muslims in what remained as India after partition stayed back in that country, where Mahatma Gandhi and independent India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, built the foundations of a secular state.

The maharaja of Kashmir initially sought independence from both countries but later chose to join India after Pakistan invaded, triggering the first war from 1947 to 1948. The ceasefire line established after that was formalised as the LoC in the Simla Agreement.

Despite this, both countries continue to assert claims to the entire region, including, in the case of India, to China-administered Aksai Chin on the eastern side.

What triggered the first Indo-Pakistan war in 1947?

The ruling Hindu maharaja of Kashmir was Hari Singh, whose forefathers took control of the region as part of an agreement with the British in 1846.

At the time of partition, Singh initially sought to retain Kashmir’s independence from both India and Pakistan.

But by then, a rebellion against his rule by pro-Pakistani residents in a part of Kashmir had broken out. Armed groups from Pakistan, backed by the government of the newly formed country, invaded and tried to take over the region.

Sheikh Abdullah, the most prominent Kashmiri leader at the time, opposed the Pakistani-backed attack. Hari Singh appealed to India for military assistance.

Nehru’s government intervened against Pakistan – but on the condition that the maharaja sign an Instrument of Accession merging Jammu and Kashmir with India. In October 1947, Jammu and Kashmir officially became part of India, giving New Delhi control over the Kashmir Valley, Jammu and Ladakh.

India accused Pakistan of being the aggressor in the conflict – a charge Pakistan denied – and took the matter to the United Nations in January 1948. A key resolution was passed stating: “The question of the accession of Jammu and Kashmir to India or Pakistan should be decided through the democratic method of a free and impartial plebiscite.” Nearly 80 years later, no plebiscite has been held – a source of grievance for Kashmiris.

The first war over Kashmir finally ended with a UN-mediated ceasefire, and in 1949, the two countries formalised a ceasefire line under an agreement signed in Karachi, Pakistan’s then-capital. The new line divided Kashmir between Indian- and Pakistani-controlled parts.

How did the situation change after the 1949 agreement?

By 1953, Sheikh Abdullah had founded the Jammu Kashmir National Conference (JKNC) and won state elections in Indian-administered Kashmir.

However, his increasing interest in seeking independence from India led to his arrest by Indian authorities. In 1956, Jammu and Kashmir was declared an “integral” part of India.

In September 1965, less than two decades after independence, India and Pakistan went to war over the region again.

Pakistan hoped to aid the Kashmiri cause and incite a local uprising, but the war ended in a stalemate, with both sides agreeing to a UN-supervised ceasefire.

How did China get a part of Kashmir?

The Aksai Chin region in the northeast of the region sits at an elevation of 5,000 metres (16,400 feet), and through history, was a hard-to-reach, barely inhabited territory that in the 19th and early 20th centuries sat at the border of British India and China.

It was a part of the kingdom that Kashmir’s Hari Singh inherited as a result of the 1846 deal with the British. Until the 1930s, at least, Chinese maps too recognised Kashmir as being south of the Ardagh-Johnson Line that marked the northeastern boundary of Kashmir.

After 1947 and Singh’s accession to India, New Delhi viewed Aksai Chin as part of its territory. But by the early 1950s, China – now under communist rule – built a massive 1,200km (745-mile) long highway connecting Tibet and Xinjiang, and running through Aksai Chin.

India was caught unaware – the desolate region had not been a security priority until then. In 1954, Nehru called for the border to be formalised according to the Ardagh-Johnson Line – in effect, recognising Aksai Chin as a part of India.

But China insisted that the British had never discussed the Ardagh-Johnson Line, and that Aksai Chin belonged to it under an alternate map. Most importantly, though, China already had boots on the ground in Aksai Chin because of the highway.

Meanwhile, Pakistan and China also had differences over who controlled what in parts of Kashmir. But by the early 1960s, they reached an agreement: China gave up grazing grounds that Pakistan had sought, and in return, Pakistan ceded a thin slice of northern Kashmir to China.

India claims this deal was illegal since, according to the Instrument of Accession of 1947, all of Kashmir belonged to it.

Back to India and Pakistan: What happened next?

Another war followed in December 1971 – this time over what was then known as East Pakistan, following a popular revolt by India-backed Bengali nationalists against Pakistan’s rule. The war led to the creation of Bangladesh. More than 90,000 Pakistani soldiers were captured by India as prisoners of war.

The Simla Agreement converted the ceasefire line into the LoC, a de facto but not internationally recognised border, yet again leaving Kashmir’s status in question.

But after India’s decisive 1971 victory and amid the growing political influence of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi – Nehru’s daughter – the 1970s saw Abdullah abandon his demand for a plebiscite and the Kashmiri people’s right of self-determination.

In 1975, he signed an accord with Gandhi, recognising India-administered Kashmir’s accession to India while retaining semi-autonomous status under Article 370 of the Indian Constitution. He later served as the region’s chief minister.

What led to a renewed drive for Kashmiri independence in the 1980s?

As ties grew between Abdullah’s National Conference Party and India’s ruling Indian National Congress, so did frustration among Kashmiris in India-controlled Kashmir, who felt that socioeconomic conditions had not improved in the region.

Separatist groups like the Jammu-Kashmir Liberation Front, founded by Maqbool Bhat, rose.

India’s claims of democracy in Kashmir faltered in the face of growing support for the armed groups. A tipping point was the 1987 election to the state legislature, which saw Abdullah’s son, Farooq Abdullah, come to power, but which was widely viewed as heavily rigged to keep out popular, anti-India politicians.

Indian authorities launched a severe crackdown on separatist groups, which New Delhi alleged were supported and trained by Pakistan’s military intelligence. Pakistan, for its part, has consistently maintained it provides only moral and diplomatic support, backing the Kashmiris’ “right to self-determination”.

In 1999, conflict erupted in Kargil, where Indian and Pakistani forces fought for control over strategic heights along the LoC. India eventually regained the lost territory, and the pre-conflict status quo was restored. This was the third war over Kashmir – Kargil is a part of Ladakh.

How have tensions over Kashmir escalated since then?

The following years saw a gradual reduction in direct conflict, with multiple ceasefires signed. However, India significantly ramped up its military presence in the valley.

Tensions were reignited in 2016 after the killing of Burhan Wani, a popular separatist figure. His death led to a rise in violence in the valley and more frequent exchanges of fire along the LoC.

Major attacks in Indian-administered Kashmir, including those in Pathankot and Uri in 2016, targeted Indian forces, who blamed Pakistan-backed armed groups.

The most serious escalation came in February 2019 when a convoy of Indian paramilitary personnel was attacked in Pulwama, killing 40 soldiers and bringing the two nations to the brink of war.

Six months later, the Indian government under Prime Minister Narendra Modi unilaterally abrogated Article 370, stripping Jammu and Kashmir of its semi-autonomous status. Pakistan condemned the move as a violation of the Simla Agreement.

The decision led to widespread protests in the valley. India deployed 500,000 to 800,000 soldiers, placed the region under lockdown, shut down internet services and detained thousands of people.

India insists that Pakistan is to blame for the ongoing crisis in Kashmir. It accuses Pakistan of hosting, financing and training the Pakistan-based armed groups that have claimed responsibility for multiple attacks in Indian-administered Kashmir over the decades. Some of these groups are also accused by India, the US, and others of attacking other parts of India – such as during the 2008 attack on Mumbai, India’s financial capital, when at least 166 people were killed over three days.

Pakistan continues to deny that it fuels violence in India-controlled Kashmir and instead points to widespread resentment among locals, accusing India of imposing harsh and undemocratic rule in the region. Islamabad says it only supports Kashmiri separatism diplomatically and morally.

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoNovak Djokovic pulls out of Italian Open ahead of French Open

-

Europe2 days ago

Europe2 days agoIdaho student killings: The latest pre-trial developments in the case of quadruple murder suspect Bryan Kohberger

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoLondon Marathon: Why more people than ever before are running marathons

-

Lifestyle2 days ago

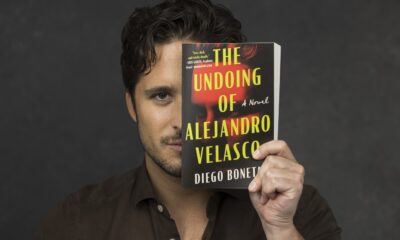

Lifestyle2 days agoDiego Boneta on debut novel ‘The Undoing of Alejandro Velasco’

-

Asia2 days ago

Asia2 days agoHong Kong 47: First batch of activists freed after four years’ prison for subversion

-

Middle East2 days ago

Middle East2 days agoPro-Palestine activist arrested in Belgium after attending protest | Israel-Palestine conflict News

-

Asia2 days ago

Asia2 days agoIndian officials investigate reports that students were served food with dead snake

-

Middle East2 days ago

Middle East2 days agoFourth round of US-Iran nuclear talks postponed amid continued tensions | Nuclear Energy News