Conflict Zones

What is in the US-Ukraine minerals deal? | Russia-Ukraine war News

After months of tense negotiations – including one particularly fiery meeting in the White House Oval Office between United States President Donald Trump and Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in February – Washington and Kyiv have finalised a long-awaited minerals deal.

The agreement, signed in Washington, DC, on Wednesday, will give the US preferential access to new Ukrainian minerals and natural resources licences. In return, the US will provide financial and military assistance to Ukraine to help the country rebuild after the war.

The deal comes at a critical moment as the US had threatened to step away from its mediation effort to bring an end to the more than three-year conflict.

Trump, who has heavily promoted the deal, said it represents “payback” for the $350bn that he claims Washington has spent on supporting Ukraine’s war effort.

It is unclear how Trump has arrived at the figure of $350bn. Official figures from the US Department of Defense put total spending on Ukraine at $182.8bn between January 2022 and December 2024.

Regardless, in Kyiv, Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal hailed the agreement as “good, equal and beneficial” for both sides.

Here’s what we know about the agreement so far.

What’s in the minerals deal?

Few details have been released about the precise terms of the deal, which was signed by US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and Ukraine’s Vice Prime Minister Yulia Svyrydenko on Wednesday.

In a statement after the signing, Bessent said the “historic” economic partnership would send a clear signal to Russia that the Trump administration is committed to a peace process that ends what he called a “cruel and senseless war”.

Under the deal, the United States-Ukraine Reinvestment Fund will be established. This fund will be jointly managed by Ukraine and the US on an equal partnership basis.

Ukraine will maintain full ownership and control of the country’s resources and will determine what and where minerals may be extracted.

Ukraine’s Ministry of Economy said the US will contribute to the fund directly or through “new military assistance”, and Kyiv will contribute 50 percent of revenues from the exploitation of natural resources via new licences in the fields of critical materials, oil and gas. Svyrydenko suggested in a post on X that this could include air defence systems for Ukraine.

📌 How will the Fund work?

The United States will contribute to the Fund. In addition to direct financial contributions, it may also provide NEW assistance — for example, air defense systems for Ukraine.

— Yulia Svyrydenko (@Svyrydenko_Y) April 30, 2025

The Ukrainian statement said: “The agreement focuses on further, not past US military assistance,” meaning that Ukraine has no debt obligations to Washington – a key point in the lengthy negotiations between the two sides.

The statement added that Ukraine expects the fund’s profits and revenues to be reinvested into Ukraine for the first decade.

What minerals does Ukraine have?

According to data from Ukraine’s Economy Ministry, the country holds deposits of 22 of the 34 minerals classified as critical by the EU. Its critical minerals include precious and non-ferrous metals, ferroalloys and minerals such as titanium, zirconium, graphite and lithium.

Ukraine also holds reserves of rare earth elements (REEs), a group of 17 metallic minerals including lanthanum, cerium and neodymium, essential for high-tech applications in electronics, defence, aerospace and renewable energy.

According to the United Nations’ Russian-language news service, Ukraine’s critical mineral reserves made up approximately 5 percent of the global supply as of 2022.

Ukraine also accounts for 7 percent of the global production of titanium.

Its lithium reserves are largely untapped and considered one of Europe’s largest, at an estimated 500,000 tonnes.

Is this a good deal for Ukraine?

Al Jazeera’s Rosiland Jordan said the deal can be viewed as a “diplomatic win” for Ukraine.

This is largely because Trump had initially insisted that Ukraine must pay back the $350bn he claims the administration of his predecessor, Joe Biden, had spent on the country since the start of the war with Russia.

“Now, [repaying that amount] was something that the Ukrainians did not want to do, and over the past couple of months, they’ve pushed to get that removed from the deal,” Jordan commented from Washington, DC. “So in a way, it can be viewed as a significant victory for Ukraine that this deal is, as some are putting it, a forward-looking deal, and not one that is looking back to the previous prosecution and financing of Ukraine’s war against Russia.”

Other analysts also noted that while the negotiations began with the US’s desire for access to Ukraine’s minerals, they have since morphed into a broader investment fund for Ukraine’s reconstruction.

“Ukraine seems to have pulled off some seriously tough negotiating with the Trump administration,” wrote Shelby Magid, the deputy director of the Eurasia Center in the Atlantic Council, a US-based think tank. “Past proposals from Washington reportedly saw the United States taking partial or total ownership of broad swaths of Ukraine’s natural resources and infrastructure… Now, Ukraine retains full ownership of its assets and has turned the deal into a joint investment fund toward the country’s future reconstruction, with only future – not past – US assistance to Ukraine counting as a contribution to the fund.”

Does the deal include US security guarantees?

No. However, under pressure from the US to make peace with Russia, President Zelenskyy has insisted that Ukraine will not enter peace talks until it has security guarantees against another war occurring in the future.

While the US-Ukraine minerals deal does not include such guarantees, analysts say it reopens the door to military assistance from Washington to Kyiv.

“It’s not a security guarantee,” said Anatol Lieven, the director of the Eurasia Program at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. “This does not say – and Trump would never offer – to send US troops to defend Ukraine, and Trump has refused to back up European proposals to send European troops to Ukraine. But what it does if it’s implemented … it ensures that the US will remain interested in Ukraine,” he told Al Jazeera.

Lieven said the deal means the US “will feel it has a stake in Ukraine”.

“And although that’s not a security guarantee, it certainly ought to be a deterrent to future Russian aggression, because it would mean that if the Russians did launch a new war, the US would certainly impose severe sanctions and would aid Ukraine militarily,” he added.

What happens next?

While the Ukrainian cabinet has approved the agreement, it still needs to be ratified by the parliament.

But more importantly, Lieven said, there needs to be peace for the deal to take effect.

“This is about private investment. The money that goes into Ukraine to develop these minerals will be private. It won’t be US state money. And of course that raises the question of whether private investors will actually see an economic motive to invest, especially given the risks involved,” he said.

“So I think this is more of a diplomatic win for Ukraine. It’s not necessarily an economic win for Ukraine.”

Conflict Zones

The $10bn India-Pakistan trade secret hidden by official data | Trade War News

In the days after gunmen killed at least 26 people in the picturesque tourist resort of Pahalgam in India-administered Kashmir last week, India and Pakistan announced a string of diplomatic moves against each other, including shutting down cross-border trade and suspending visas.

New Delhi accused Islamabad of involvement in the April 22 attack, suspended India’s participation in an Indus River water-sharing agreement that ensures Pakistan’s water supply and trimmed down diplomatic missions.

Islamabad has denied India’s accusations, called for a neutral investigation into the attack and announced it would suspend all trade with India, including through third countries, among other retaliatory measures. India-Pakistan trade relations have been frozen since 2019.

Both countries have also closed the Wagah-Attari crossing, the main land border between India and Pakistan.

But while official figures show minimal trade between the neighbouring countries, experts said billions of dollars of hidden, backdoor trading does continue.

So what is the real scale of trade between these archrivals? And will the suspension of trade and closure of the land border truly impact trading still taking place between the two countries?

Have India and Pakistan traded freely in the past?

Yes. Trade between India and Pakistan began after the two countries were created out of British India in 1947 through partition.

Trading volumes grew when New Delhi bestowed Islamabad with the “most favoured nation” (MFN) status in 1996 – a World Trade Organization rule that ensures a country treats all its trading partners equally with respect to tariffs and trade concessions.

But amid broader bilateral tensions between the nuclear armed neighbours, trade never fully took off. At least officially.

In the financial year 2017-2018, total trade between India and Pakistan stood at $2.41bn, compared with $2.27bn in 2016-2017. India exported goods worth $1.92bn to Pakistan and imported goods valued at $488.5m.

But in 2019, India revoked Pakistan’s MFN status after a suicide bombing in Pulwama in India-administered Kashmir killed at least 40 Indian paramilitary personnel.

From 2018 to 2024, bilateral trade fell from $2.41bn to $1.2bn. Pakistani exports to India plummeted from $547.5m in 2019 to just $480,000 in 2024.

How much and what do India and Pakistan officially trade now?

According to India’s Ministry of Commerce, the country’s exports to Pakistan from April 2024 to January 2025 amounted to $447.7m. Pakistan’s exports to India during the same time period were just $420,000.

India’s exports include pharmaceuticals, petroleum, plastic, rubber, organic chemicals, dyes, vegetables, spices, coffee, tea, dairy products and cereals.

Pakistan’s main exports include copper, glassware, organic chemicals, sulphur, fruits and nuts, and certain oilseeds.

Shantanu Singh, an international trade lawyer based in India, told Al Jazeera that due to the current trade ban, the immediate impact will be witnessed in Pakistan’s pharma sector: Pharmaceutical products are Islamabad’s main imports from India.

He also noted that the closure of the Wagah-Attari Integrated Check Post (ICP), which was the only land port through which trade was permitted between India and Pakistan, will increase the cost of trade.

“So typically, land ports allow for a lower cost and ease of transport, and with the closure of this land port, you would see a rise in costs of any kind of trade. It will also particularly hurt trade from Afghanistan since imports from Afghanistan utilised this land route. The local economy built around the ICP is also likely to be affected,” Singh added.

Is real trade between India and Pakistan higher?

While official figures have pegged Indian exports to Pakistan at $447.65m, the real trade volume is thought to be much higher as traders route goods via third countries to bypass restrictions, avoid scrutiny and command higher prices upon relabelling.

Unofficial Indian exports to Pakistan are in fact believed to stand at $10bn a year, according to the India-based think tank Global Trade Research Initiative (GTRI).

How does this unofficial trade work?

GTRI said this has been achieved largely by finding alternate routes through ports in Dubai in the United Aab Emirates; Colombo in Sri Lanka; and Singapore.

Explaining how the system works in a LinkedIn post, GTRI founder Ajay Srivastava said: “Indian goods are sent to Dubai, Singapore, and Colombo. The goods are then stored in bonded warehouses in transit hubs. While in storage – still duty-free – the documents and labels are changed. The products are re-exported to Pakistan under a new ‘country of origin’ – say, UAE instead of India.”

Srivastava added that while such trade is not always illegal, “this grey-zone strategy highlights how trade adapts faster than policy.”

He added that such trade, by bypassing formal trade restrictions, “fetches better prices, even after re-export markups and it maintains plausible deniability – no ‘official’ trade, yet commerce continues”.

Does this sort of trade happen elsewhere?

Yes. Foreign trade experts said rerouting goods by taking them to facilities where they are transferred to other ships to avoid international trade restrictions is a common practice.

India, for instance, has been a location for such practices since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, said Jayati Ghosh, economics professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. They reroute fuel from Russia to European countries, such as Germany, to skirt sanctions, Ghosh said.

Since the Ukraine invasion, India has become one of the largest buyers of Russian crude oil, importing an average of 1.75 million barrels per day in 2023, a 140 percent increase from 2022. Russian oil accounted for about 40 percent of India’s total crude imports in 2024, up from just 2 percent in 2021.

China has been doing the same with India for decades, trade economist Biswajit Dhar said, by routing goods to India via the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, which includes Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Myanmar.

“If China brings exports directly to India, they attract higher tariffs. With ASEAN, India has a retail agreement,” Dhar said. “Businesses will do everything possible to meet a demand wherever it exists in whichever country.”

Will informal trade between Pakistan and India continue?

Since the Kashmir attack, government officials in India have been collating data on indirect exports to Pakistan and are reportedly lobbying to curb the practice. Pakistan’s latest trade ban against India includes trading through third countries, which means the authorities in Pakistan are also well aware of this informal trade.

Preventing it could be tricky, however, as rerouting and relabelling goods in third countries are carried out by private entities, including importers, exporters and traders, and not through official government channels, according to Singh.

“It is really for the customs agencies in Pakistan to determine whether the relevant nonpreferential rules of origin, if any, in Pakistan are met,” Singh said.

“This is usually done through some sort of provision of proof that the importer of the product has to provide to satisfy the requirements that may be there in the law in Pakistan. So this is a question for the authorities in Pakistan to determine whether the good is actually originating in the third country or is it in fact a circumvented good which is coming from India.”

The challenge now is for customs authorities in Pakistan to determine how to tackle this circumvention through third countries, Singh said.

“That would require them, to some extent, to increase the scrutiny of the goods which are coming into Pakistan.”

Ultimately, it will be hard to prevent this trade because it meets demand. “This trade is bound to happen because [India and Pakistan] have common cultures. And there is a huge demand for Indian products in Pakistan,” he said. “That demand has to be met from somewhere.”

Traders are unlikely to want to relinquish a business that provides higher profit margins than official trade.

“This tactic [banning trade via third countries] works when we believe that the traders will act honestly and that the Indian traders will understand the message that the government of India is trying to convey by these measures,” Singh said.

“However, if the traders don’t want to do that, if they want to be unscrupulous, then there is nothing that can be stopped,” Dhar said.

Have India and Pakistan sparred over trade before?

Yes.

The 1965 Indo-Pakistani War severely disrupted trade, leading to a suspension of economic ties, but the Tashkent Agreement in 1966 restored diplomatic and economic relations, allowing trade to resume gradually.

The 1971 war resulting in the creation of Bangladesh further strained relations and trade halted during the conflict. The Simla Agreement in 1972 emphasised peaceful resolution of disputes, indirectly supporting trade normalisation. But trade ties have continued to be on a seesaw for decades.

The 2019 suicide bombing in Pulwama strained bilateral trade further. After the attack, India slapped an import duty of 200 percent on all goods from Pakistan, including fresh fruit, cement and mineral ore.

Six months later, in August 2019, India unilaterally revoked the semiautonomous status of the part of Kashmir it controls and reorganised the erstwhile state into two federally governed territories.

Pakistan, which never gave India MFN status, further downgraded diplomatic relations with India and suspended trade after New Delhi’s Kashmir moves. Since then, talks to resume trade with India have not taken place.

Conflict Zones

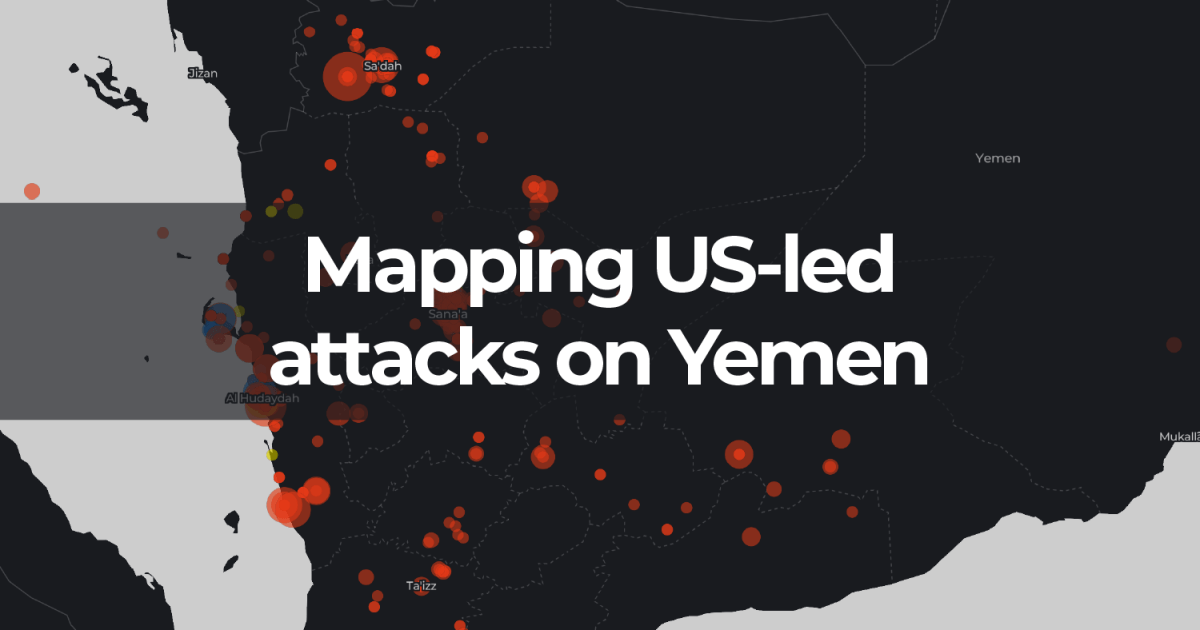

Animated maps show US-led attacks on Yemen | Interactive News

The Red Sea is a vital waterway for global trade, connecting the Mediterranean Sea with the Gulf of Aden through the Suez Canal. Approximately 12 percent of global shipping traffic normally passes through the Red Sea, including key oil shipments and commercial goods.

The Red Sea attacks began on November 19, 2023, when Houthi forces seized Galaxy Leader, a British-owned, Japanese-operated vehicle carrier, off the coast of Hodeidah. The 25-person crew was detained, and the ship was held for more than a year.

The Houthis justified the seizure as an act of solidarity with Palestinians, stating they would continue their actions until Israel’s war on Gaza came to an end.

Since November 2023, the Houthis have carried out more than 100 attacks, including missile, drone and boat raids, targeting Israel-linked commercial vessels as well as US and UK military ships in the Red Sea. The attacks have resulted in two ships being sunk and one seized.

The map below shows some of the locations of these attacks.

Yemen’s devastation over the past decade

The war in Yemen has left the country in severe poverty.

The country has been divided between the Houthis, also known as Ansar Allah, who control the west, including Sanaa, and the internationally recognised Yemeni government, which controls the south and east, with Aden as its capital.

Since 2015, the civil war in Yemen, with the intervention of a Saudi-led coalition on the government’s side, has devastated the country.

More than 4.5 million people have been displaced and 18.2 million need humanitarian aid. The risk of nationwide famine is at its highest, with nearly five million people facing acute food insecurity, according to the United Nations Refugee Agency.

Conflict Zones

Kashmir attack: How India might strike Pakistan – what history tells us | Border Disputes News

Pakistan said on Wednesday that it had “credible intelligence” that India might launch a military strike against it within the next few days.

Meanwhile, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi led a series of security meetings on Tuesday and Wednesday, adding to speculation of an impending Indian military operation against its archrival, after the April 22 attack on tourists in Pahalgam in Indian-administered Kashmir in which 26 people were killed.

Since the attack, barely existent relations between the nuclear-armed South Asian neighbours have nosedived further, with the countries scaling back diplomatic engagement, suspending their participation in bilateral treaties and effectively expelling each other’s citizens.

The subcontinent is on edge. But how imminent is an Indian military response to the Pahalgam killings, and what might it look like? Here’s what history tells us:

What happened?

Pakistan’s Information Minister Attaullah Tarar said in a televised statement early on Wednesday that Islamabad had “credible intelligence” that India was planning to take military action against Pakistan in the “next 24 to 36 hours”.

Tarar added that this action would be India’s response on the “pretext of baseless and concocted allegations of involvement” in Pahalgam. While India has alleged Pakistan’s involvement in the Pahalgam attack, Islamabad has denied this claim.

India and Pakistan each administer parts of Kashmir, but both countries claim the territory in full.

Tarar’s statement came a day after Modi gave the Indian military “complete operational freedom” to respond to the Pahalgam attack in a closed-door meeting with the country’s security leaders, multiple news agencies reported, citing anonymous senior government sources.

On Wednesday, Modi chaired a Cabinet Committee on Security meeting, the second such meeting since the Pahalgam attack, state-run Doordarshan television reported.

Meanwhile, as the neighbours continued to exchange gunfire along the Line of Control (LoC) dividing Indian and Pakistan-administered Kashmir, other world leaders stepped up diplomacy to calm tensions.

“We are reaching out to both parties, and telling … them to not escalate the situation,” a United States state department spokesperson told reporters on Tuesday, quoting US Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who is expected to speak to the foreign ministers of India and Pakistan.

Also on Tuesday, the spokesperson for United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said that he had spoken to Pakistan Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif and Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, offering his help in “de-escalation”.

What military action could India take?

While it is unclear what course of action India could take, it has in the past used a range of military tactics. Here are some of them:

Covert military operations

By design, they aren’t announced – and aren’t confirmed. But over the decades, India and Pakistan have each launched multiple covert raids into territory controlled by the other, targeting military posts, killing soldiers – and on occasion beheading the enemy’s troops.

These strikes are often carried out as a retaliatory step by a military unit whose personnel were themselves previously attacked, as a form of retribution.

But such raids are never confirmed: The idea is to send the other country a message but not force it to respond, thereby containing the risk of escalation. Public announcements lead to domestic pressure on governments to hit back.

Publicised ‘surgical strikes’

Sometimes, though, the idea is not to send subtle messages – but to embarrass the other country by making an attack public. It also doesn’t hurt politically.

India has in the past carried out so-called surgical strikes against specific, chosen targets across the LoC – most recently in 2016.

Then, after armed fighters killed 17 Indian soldiers in Uri, Indian-administered Kashmir, special forces of the Indian Army crossed the de facto border to attack “launch pads” from where, New Delhi alleged, “terrorists” were planning to strike India again. “The operations were basically focused to ensure that these terrorists do not succeed in their design of infiltration and carrying out destruction and endangering the lives of citizens of our country,” Lieutenant General Ranbir Singh, then the director-general of military operations for the Indian Army, said in a public statement, revealing the raid.

India claimed that the surgical strike had killed dozens of fighters, though independent analysts believe the toll was likely much lower.

Aerial strikes

In February 2019, a suicide bomber killed 40 Indian paramilitary soldiers in Pulwama in Indian-administered Kashmir, weeks before national elections in the country. This attack was claimed by the Jaish-e-Muhammad, an armed group based in Pakistan.

Amid an outpouring of rage, the Indian Air Force launched an aerial raid into Pakistan-administered Kashmir. India claimed it had struck hideouts of “terrorists” and killed several dozen fighters.

Pakistan insisted that Indian jets only hit a forested region, and did not kill any fighters. Islamabad claimed it scrambled jets that chased Indian planes back across the LoC.

But a day later, Indian and Pakistani fighter jets again engaged in a dogfight – this one ending with Pakistan downing an Indian plane inside territory it controls. An Indian fighter pilot was captured, and returned a few days later.

Attempts at taking over Pakistan-controlled land

Over the past few years, there have been growing calls in India that New Delhi should take back Pakistan-administered Kashmir. That chorus has only sharpened in recent days after the Pahalgam attack, with even leaders of the opposition Congress Party goading the Modi government to take back that territory.

While retaking Pakistan-administered Kashmir remains a policy objective of every Indian government, the closely matched military capabilities of both sides make such an endeavour unlikely.

Still, India has a track record of successfully taking disputed territory from Pakistan.

In 1984, the Indian Army and Indian Air Force launched Operation Meghdoot, in which they rapidly captured the Siachen glacier in the Himalayas, blocking the Pakistan Army from accessing key passes. One of the world’s largest non-polar glaciers, Siachin has since been the planet’s highest battleground, with Indian and Pakistani military outposts positioned against each other.

Naval missions

In the aftermath of the Pahalgam attack, the Indian Navy announced that it had carried out test missile strikes.

“Indian Navy ships undertook successful multiple anti-ship firings to revalidate and demonstrate readiness of platforms, systems and crew for long range precision offensive strike,” the navy said in a statement on April 27.

“Indian Navy stands combat ready, credible and future ready in safeguarding the nation’s maritime interests anytime, anywhere, anyhow.”

Many analysts have suggested that the trials were a show of strength, pointing to the Indian Navy’s ability to strike Pakistani territory if ordered to do so.

A full-blown military conflict

India and Pakistan have gone to war four times in the 78 years of their independent existence. Three of these armed conflicts have been over Kashmir.

Two months after the British colonial government left the subcontinent in August 1947 after carving it up into India and Pakistan, the neighbours fought their first war over Kashmir, then ruled by a king.

Pakistani militias invaded Kashmir to try and take control. The king, Hari Singh, pleaded with India for help. New Delhi agreed, and joined the war against Pakistan, but on the condition that Singh sign an instrument of accession, merging Kashmir with India. The king agreed.

The war finally ended on January 1, 1949, with a ceasefire agreement. India and Pakistan have both held parts of Kashmir since then.

In 1965, a clash between their border forces escalated into a full-blown war. Pakistani forces crossed the ceasefire line into Indian-administered Kashmir, while Indian forces crossed the international border into Pakistan’s Lahore and launched attacks. After thousands of casualties on both sides, a United Nations Security Council resolution helped the neighbours end the war.

In 1971, Pakistan and India were embroiled in an armed conflict over East Pakistan, where Indian forces helped liberate the territory, leading to the establishment of Bangladesh. In 1972, the two countries signed the Simla Agreement, which established the LoC.

In 1999, the Pakistani military crossed the LoC, sparking the Kargil War. Indian troops pushed the Pakistani soldiers back after bloody battles in the snowy heights of the Ladakh region.

-

Lifestyle2 days ago

Lifestyle2 days agoAfter a year of turmoil, The Washington Post is taking note of its journalism again

-

Africa2 days ago

Africa2 days agoResearchers study using planes to cool the earth amidst global warming

-

Africa2 days ago

Africa2 days agoBomb Blast Kills 26 in Northeast Nigeria

-

Conflict Zones2 days ago

Conflict Zones2 days agoAbout 600 North Korean soldiers killed in war in Ukraine, lawmakers say | Russia-Ukraine war News

-

Asia2 days ago

Asia2 days agoFall of Saigon: US officers who broke rank to save lives recall final days of Vietnam War 50 years on

-

Middle East1 day ago

Middle East1 day agoIran hangs man convicted of spying for Israel’s Mossad | Espionage News

-

Europe1 day ago

Europe1 day ago16-year-old suspect detained after 3 killed in shooting in Sweden

-

Lifestyle2 days ago

Lifestyle2 days agoAP PHOTOS: LGBTQ+ models showcase Lady Gaga-inspired outfits at Rio de Janeiro train station