CNN

—

As servicemen aboard the US Navy aircraft carrier dumped millions of dollars of military hardware into the South China Sea, the commander chose not to watch.

Capt. Larry Chambers knew his order to push helicopters off the flight deck of the USS Midway could cost him his military career, but it was a chance he was willing to take.

Above his head, a South Vietnamese air force major, Buang-Ly, was circling the carrier in a tiny airplane with his wife and five children aboard and needed space to land.

It was April 29, 1975. To the west of where the Midway was operating, communist North Vietnamese forces were closing in for the capture of Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, which the US had supported for more than a decade.

Buang feared his family would pay a terrible price if captured by the communists. So, he jammed his family aboard the single-engine Cessna Bird Dog he found on minor airstrip near Saigon, headed out to sea – and hoped.

And luckily Buang ran into another “idiot,” as Chambers puts it.

“I figured, well, if he’s brave enough or dumb enough to come out and think some other idiot is going to clear the deck (of a US Navy aircraft carrier) of a whole bunch of helicopters to give him a personal runway to land on …” Chambers told CNN, with a chuckle and a scratch of his head as if still not believing the crazy episode.

The Midway’s deck was crowded with helicopters that Tuesday because it was assisting in Operation Frequent Wind, the helicopter evacuation of Saigon.

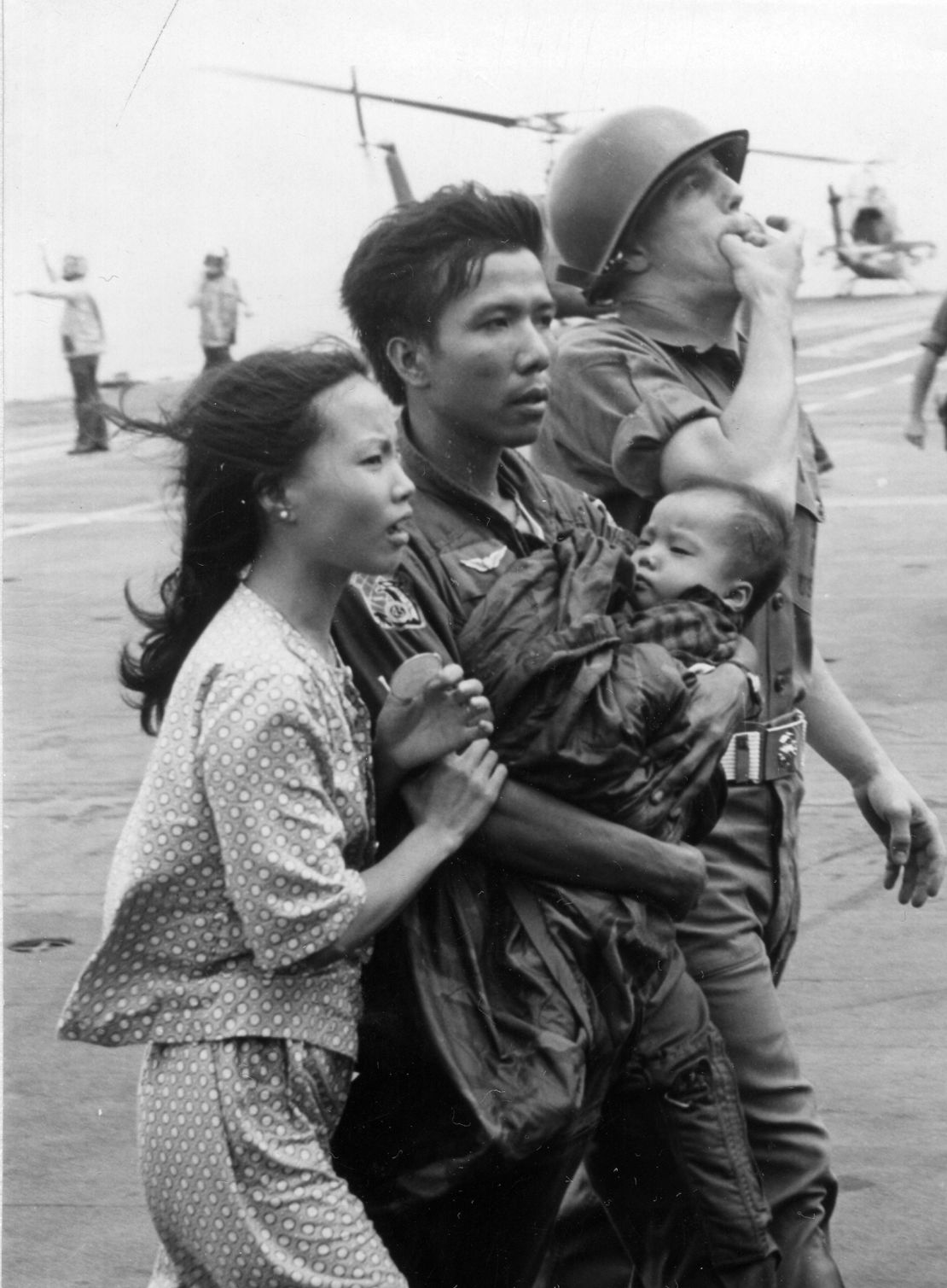

Some 7,000 South Vietnamese and Americans would make their way onto US Navy ships on April 29 and 30 in frenzied escapes from Saigon. Some 2,000 of them found their way onto Midway. But few could rival the drama of the family of seven in that two-seat Cessna.

Buang had no radio and so the only way to let the captain of the Midway know he needed help was to drop a handwritten note onto its deck as he flew overhead.

Several attempts failed before finally one found its mark.

“Can you mouve [sic] these Helicopter to the other side, I can land on your runway, I can fly 1 hour more, we have enough time to mouve. Please rescue me, Major Buang wife and 5 child,” it read.

Capt. Chambers had a choice to make: clear the deck as Buang requested; or let him ditch in the ocean. He knew the aircraft, with its fixed landing gear, would flip over once it hit the water. Even if it held together, flipping would doom the family to drowning.

He couldn’t let that happen, he said, even though his superiors did not want the small aircraft to land on the carrier.

Neither did the Midway’s air boss, who ran flight deck operations.

“When I told the air boss we’re going to make a ready deck (for the small plane), the words he had to say to me I wouldn’t want to print,” Chambers said.

Chambers said he ordered all of the ship’s 2,000-person air wing up to the deck to prepare to receive the small plane and turned his ship into the wind to make a landing possible.

Crewmen pushed helicopters – worth $30 million by some accounts – off the deck. American, South Vietnamese, even CIA choppers splashed into the waves.

Chambers still doesn’t know exactly how many. “In the middle of chaos, nobody was counting,” he said.

And he wasn’t looking.

Because he was disobeying the orders of his superiors in the US fleet, he knew his decision could land him a punishment that included being kicked out of the Navy.

“I knew that I was going to have to face a (court martial) board. And I wanted to be able to say, even with the lie detector, that I didn’t know how many we actually pushed over the side,” Chambers told CNN, explaining his decision not watch as his orders were executed.

“So that was my defense. It was kind of a stupid idea at the time, but at least it gave me the confidence to go ahead and do it.”

With enough space cleared, Buang touched down on the Midway. Crewman grabbed onto the light plane with their bare hands to make sure it wasn’t blown off the deck in the strong winds coming across it. The rest of the crew cheered.

“He’s probably the bravest son of a bitch I’ve run into in my whole life,” said of Buang, adding that the South Vietnamese pilot was trying save his family by landing on an aircraft carrier – something he’d never done before – in a plane not designed for that.

“I was just clearing the runway for him … that’s all you can do.”

And life came before hardware, he said.

“We do the best we can saving human lives. That’s the only thing you can do.”

The fall of Saigon brought the final curtain down on a grinding conflict that unleashed devastation across the region, cost more than 58,000 American and millions of Vietnamese lives, saw the might of US military power fought to a bloody stalemate and triggered huge social unrest at home.

The 50th anniversary on Wednesday will trigger complex and mixed emotions for those who lived through it.

For Vietnam’s government, still run by the same Communist Party that swept to victory, it will be a week of huge parades and celebrations, officially known as “Liberation of the South and National Reunification Day.” For those South Vietnamese who had to flee, many of whom settled in the US, the anniversary has long been dubbed “Black April.”

For US veterans, it will once again raise the age-old question – what was it all for?

Chaos ruled Saigon in the last week of April 1975.

Though more than a decade of US military involvement in the Vietnam War had officially ended with the signing of the Paris Peace Accords with North Vietnam in January 1973, the deal didn’t guarantee an independent state in the South.

The administration of US President Richard Nixon had pledged to keep up military aid for the government in Saigon, but it was a hollow promise that would not last into the era of his successor Gerald Ford. Americans, tired of a divisive war that had cost so many lives and hundreds of billions in taxpayer dollars, were broadly unsupportive of the South Vietnamese regime.

In early March 1975, North Vietnam launched an offensive into the South that its leaders expected would lead to the capture of Saigon in about two years. Victory would come in two months.

On April 28, North Vietnamese forces attacked Tan Son Nhut Air Base in Saigon, making an evacuation by airplane impossible. There was no other place in the city that could handle large aircraft.

With helicopter evacuation the only option, Washington launched Operation Frequent Wind.

When Bing Crosby’s seasonal classic “White Christmas” played over the radio, that was the signal for Americans and select Vietnamese civilians to go to designated pickup spots to be airlifted out of the city.

More than 100 helicopters, operated by the US Marine Corps, the US Air Force and the CIA, would deliver evacuees to US Navy ships waiting offshore.

By command of the president (not really)

While Capt. Chambers was making command decisions at sea, American helicopter pilots were doing so above Saigon.

Marine Corps Maj. Gerry Berry flew from a US ship offshore to Saigon 14 times during the evacuation, the last of those flights marking the official end of the US presence in South Vietnam.

But getting to that point wasn’t straightforward.

Berry, the pilot of a twin-rotor CH-46 Sea Knight helicopter, got orders on the afternoon of April 29 to fly to the US Embassy in Saigon and get Ambassador Graham Martin out.

But nobody seemed to have told Martin or the US Marines guarding the embassy.

Upon touchdown, when he told the guards he was there to pick up the ambassador, they ushered about 70 Vietnamese evacuees aboard the aircraft instead, he said.

Subsequent flights from an offshore US Navy ship were greeted with more and more evacuees – and no US envoy.

With each flight to and from the embassy, Berry could see the crowds outside the it growing – and North Vietnamese forces drawing closer.

“I remember thinking at the time, ‘Well, we can’t finish this,’” he told CNN.

But he knew someone had to take charge, to at least get the ambassador out.

Around 4 a.m., he could see the North Vietnamese forces closing on the embassy.

“The tanks were coming down the road. We could see them. The ambassador was still in there,” he said.

Landing on the roof, the Sea Knight took on another stream of evacuees – and no Ambassador Martin.

Berry called a Marine guard sergeant over to the cockpit – and told him he had direct orders from President Ford for the ambassador to get on the helicopter.

“I had no authorization to do that,” Berry said. But he knew time was short, and his frustration at making this trip more than a dozen times was boiling over.

“I basically ordered him out, when I said in my best aviator voice, ‘The president sends. You have got to go now,’” using military terminology for how an order is handed down.

He said Martin seemed happy to finally get a direct order, even if it came from a Marine pilot.

“It looked like an Olympic sprint team getting on that (aircraft). So you know, I’ve always said that all he wanted to do was be ordered out by somebody,” Berry said.

With the envoy aboard, the Sea Knight headed out to the USS Blue Ridge, ending Berry’s 14th flight of Operation Frequent Wind, some 18 hours after he started.

Hours later North Vietnamese tanks would break through the gates of the South Vietnamese presidential palace, not far from the US Embassy. The Vietnam War was over.

Berry and Chambers were both officers who had to make decisions – outside or against the chain of command – that saved lives during the fall of Saigon, which was soon renamed Ho Chi Minh City by the victorious North Vietnamese.

And Chambers says it is a quality that sets the US military apart from its adversaries to this day.

“We have young kids … taught initiative to do things and to take responsibility, unlike some of the other militaries where the commissar, or whoever it is,” looms over every decision, Chambers said.

“We want everybody to think, and everybody to act,” said Chambers, who as a Black man was the first person of color to command a US Navy aircraft carrier.

“You’ve got to be the guy in charge. You can’t run things all the way up through the Pentagon every time you have to do something,” Berry said.

Chambers never faced any disciplinary action for his decisions aboard the Midway off Saigon. He’s not sure if that’s because the Midway wasn’t the only ship dumping helicopters overboard that day or because he was quickly dispatched on another rescue mission.

And it certainly didn’t hurt his naval career. Two years after dumping those helicopters into the sea, he was promoted to rear admiral.

Pilot Berry, who also served a combat tour in Vietnam in 1969 and ’70, is also left with sadness at the war’s futility.

“I hate to think all those deaths were for naught, the 58,400,” he said.

“What did we gain by all that, you know? And we killed more than a million Vietnamese.”

“Those people not only lost that life, but they lost the life where they would have had families and all those things,” Berry said.

As the 50th anniversary of his evacuation flights neared, Berry, now 80, was asked how long Americans would remember the Fall of Saigon, which brought to a close one of the US military’s greatest failures.

“With the number of lives we lost… it can’t be called a victory. It just can’t be,” Berry said.

But Vietnam also provides lessons 50 years later about keeping your trust with allies and friends, like NATO and Ukraine, he said.

“We had all that promised aid for South Vietnam that never came after the final assault” began in March 1975, he said.

“We never, never delivered.

“You promise something, you should follow through.”