Education

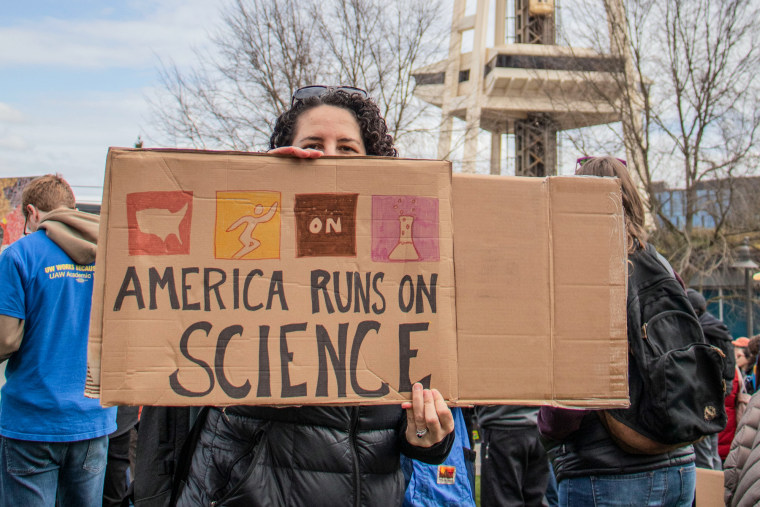

The best and brightest young scientists are looking beyond the U.S. as cuts hit home

Jack Castelli had it all figured out.

The University of Washington doctoral student had spent the past three years developing new gene-editing techniques that could spur immunity to the virus that causes AIDS. Early testing in mice showed promising results. His research group hoped it could develop into a treatment, or even a cure, for HIV.

Castelli, who is Canadian, saw two career paths after his graduation this spring: He could join a U.S. biotech company, or he could find a postdoctoral position at a U.S. university or research laboratory.

“This is where the money is at and where all the clinical trials are happening,” Castelli said, making the U.S. “the only place in my mind I could push that forward.”

Then the Trump administration’s science cuts hit.

And so, on a rainy late April day in Seattle, Castelli stood at a lectern before his friends and family and defended his doctoral thesis — about using stem cells to express antibodies against HIV — with his scientific life at a crossroads.

Should he join a lab in his native Canada? Accept recruiting calls to a European university? A Chinese biotech company? They were all possibilities now, and his U.S. visa is likely to expire in a few months’ time.

“I have a personal interest in Jack getting the best opportunity for himself, and as much as I’d love to say the U.S. is the place, I can’t necessarily say that right now,” said Jennifer Adair, who was Castelli’s principal investigator at the Fred Hutch Cancer Center, a partner institute to the university.Castelli speaks three languages fluently and completed two internships while earning his doctoral degree. He is a generous colleague and an exceptional scientist, Adair said.

But his uncertain future is hardly unique. The Trump administration’s slowdown in science funding — which stalled thousands of grants at the National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation, among other organizations — has left U.S.-based scientists and researchers scrambling to find homes for promising work that could lead to medical treatments and cures. Now many are looking abroad. As of May, Castelli had not made a decision on whether he’ll stay in the U.S.

The slowdown has forced the University of Washington, a top public university for biomedical research, to implement a hiring freeze, travel restrictions, class size reductions and furloughs. Some departments are pushing students to graduate sooner than expected. In a court filing, a university representative said it funds about 3,000 researchers through NIH grants.

Interviews with more than 20 graduate students, faculty members and university administrators at UW describe a research hub thrown into chaos. Other institutions have made similarly drastic moves, according to court filings in lawsuits that aim to thwart the cuts.

Many of those interviewed said a generation of scientists — and the innovations their research would bring — could be decimated.

“Really talented people are not able to get jobs; other really talented people are able to get jobs, but they’re choosing not to take them because of the craziness,” said David Baker, a professor of biochemistry at the University of Washington School of Medicine, who won the Nobel Prize in 2024 for protein research. “Why would you stay in a country where there’s not really an obvious commitment to science, when you could go somewhere else and be better funded and not worry about what you can read in the news or what email you’re going to get?”In an April 14 court filing, the university’s vice provost for research, Mari Ostendorf, said the campus mood had dimmed.

“Faculty and staff don’t know if their funding will be cut, if their research will be terminated, whether they will be able to attend conferences, or even whether they will continue to have jobs,” Ostendorf wrote. “Funding gaps have forced researchers to abandon studies, miss deadlines, or lose key personnel.”

A spokesperson for the National Institutes of Health declined to comment.

And there may be even more funding lost in the future due to Trump administration decisions. After a protest at the University of Washington campus Monday over the war in the Gaza Strip, the Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees NIH, announced that it was part of a task force reviewing UW’s response to the demonstration.

About 30 people were arrested after occupying a campus building Monday, according to the university, which condemned the protest in a statement and described it as “dangerous” and “violent.”

The Trump administration previously canceled federal grants at Columbia University during a similar review and has said Harvard University will receive no new grants until it makes a series of reforms, including changes to policies about protests and antisemitism.

Although the review was only announced Tuesday, the administration’s Task Force to Combat Anti-Semitism said in a news release that “the university must do more to deter future violence and guarantee that Jewish students have a safe and productive learning environment,” adding that it expected UW “to follow up with enforcement actions and policy changes.”

A university science laboratory operates like a small factory where workers are churning out ideas, research and data, rather than furniture or light bulbs. Traditionally, these labs’ primary customers are federal science agencies, like NIH or NSF.

Think of a lab’s principal investigator as akin to a company president. In the grant process, they must convince the government or private funders to buy their product — unique research — and then pay graduate students in wages and tuition.

“I’m like a small-business owner,” said Adair, who recently left Seattle to serve as a professor and associate director at the UMass Chan Medical School’s gene therapy center. “I have to pay myself. I have to pay my staff. I have to find the money to do the research.”In the first few months of 2025, funding for NIH grants has lagged the year prior by at least $2.3 billion, according to STAT News. NIH has also canceled grant applications as it targets politically disfavored topics like infectious diseases, according to critics.

That funding slowdown has forced many principal investigators to reduce their lab’s size.

“We’ve had to make personnel cuts,” said Alex Greninger, a professor of laboratory medicine at UW Medicine, adding that he had been forced to rescind a job offer to a postdoctoral researcher from China who had been doing research in his lab for nearly three years.

It cost the researcher her visa, he said. Another member of his lab left to take a job at a Chinese gene synthesis firm. Several have seen placements rescinded at other institutions.

“This is the first year where people didn’t get into graduate school,” Greninger said, about technicians in his lab who have completed undergraduate degrees, adding that they had done “everything right.”

Dr. Anna Wald, the head of allergy and infectious diseases at UW Medicine, the university’s school of medicine and hospital system, said several principal investigators in her department cut part of their own salaries to keep their staffers on.

Meanwhile, Adair paid out of her own pocket to send students to conferences that could advance their careers.

The uncertainty has also simply wasted time, some said.

“Everybody is spending a lot of time dealing with changes in how the university operates,” said Jakob Von Moltke, an associate professor of immunology at the University of Washington. “Everything just functions less efficiently and there’s less innovation.”

With so many professors uncertain about funding, many first-year graduate students seeking a lab are struggling to find positions. At some UW departments, first-year graduate students often rotate between labs for several months before they select a home for the following four or five years.

“A lot of people are scrambling to find a lab to settle into and a lot of faculty are unable to commit to taking students, or backing out of commitments,” said Dustin Mullaney, a first-year doctoral student studying molecular and cellular biology.

Still, many first-years consider themselves lucky — at least they got in. Most UW departments have reduced upcoming graduate classes by 25%-50%, according to court filings in a case filed by 16 state attorneys general aiming to restore the flow of NIH funding.

“I think we are going to lose most of a generation of scientists,” said Henry Mangapalli, a first-year doctoral student in the laboratory medicine department.

Meanwhile, doctoral students nearing graduation say they’re being recruited to move abroad.

Kristin Weinstein, a fourth-year doctoral student in the department of immunology working on autoimmune research, planned to graduate next year, find a postdoctoral research position at a U.S. university and eventually become a professor.

But now, faced with hiring freezes and shrinking labs, Weinstein said she’s considering moving her family, including an infant son, out of the U.S. Before UW’s austerity actions, Weinstein booked travel to Switzerland so she could present her research at the World Immune Regulation Meeting 2025, a key conference in her field.“What it turned into was a lot of informational interviewing,” Weinstein said. “I talked to faculty who are in Australia, faculty who are in Germany, faculty who are in Luxembourg and Denmark. … There was active recruiting happening.”

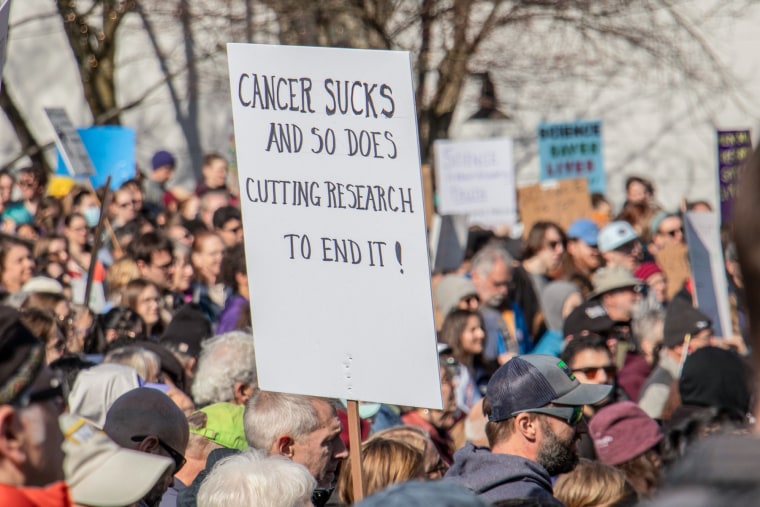

Baker, the Nobel winner who directs the Institute for Protein Design, said that more than 15 of his graduate students and postdoctoral researchers were aiming for new roles overseas. Meanwhile, other students have seen their research upended.

Nelson Niu, a fourth-year doctoral student in mathematics, said he had planned to spend six years teaching students and completing his thesis, a timeline sanctioned by his department. But on March 11 he received an email from his department chair saying the policy had changed for fourth-year students because of new financial realities, and people like Niu were now only guaranteed five years of funding.

“Jarring,” Niu said of the notice; now he’d have to pack two years of study into one.

Arjun Kumar, a third-year doctoral student studying why T cells lose their ability to fight off tumors, was working with National Cancer Institute researchers to potentially apply some of his research findings to a type of treatment pioneered there.

But Kumar said he lost weeks of time after the NIH placed a temporary communications freeze on federal researchers this winter.

“They were already working on key experiments for us and they already had data they couldn’t send us because they couldn’t email us,” Kumar said.Later, Kumar learned the NCI researchers no longer had the bandwidth to help.

“It was an exciting collaboration that was snuffed out in the moment,” Kumar said.

Washington is one of 16 states suing the NIH and HHS over its slowdown in grant funding. A judge will hear arguments Thursday as the state attorneys general seek a preliminary injunction.

Meanwhile, the pressure on scientists to leave the U.S. is only increasing. On Monday, the European Union launched a drive to attract scientists to Europe, and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced a commitment of $566 million to attract U.S. talent and “make Europe a magnet for researchers.”

“It has been really challenging to my identity as an American citizen to think about having to leave the country to pursue my career,” Weinstein said. “It feels like the American dream is dead.”

Education

Trump administration says Harvard will receive no new grants until it meets White House demands

WASHINGTON — Harvard University will receive no new federal grants until it meets a series of demands from President Donald Trump’s administration, the Education Department announced Monday.

The action was laid out in a letter to Harvard’s president and amounts to a major escalation of Trump’s battle with the Ivy League school. The administration previously froze $2.2 billion in federal grants to Harvard, and Trump is pushing to strip the school of its tax-exempt status.

Harvard has pushed back on the administration’s demands, setting up a closely watched clash in Trump’s attempt to force change at universities that he says have become hotbeds of liberalism and antisemitism.

In a press call, an Education Department official said Harvard will receive no new federal grants until it “demonstrates responsible management of the university” and satisfies federal demands on a range of subjects. It applies to federal research grants and not federal financial aid students receive to help cover tuition and fees.

The official spoke on condition of anonymity to preview the decision on a call with reporters.

Follow live politics coverage here

The official accused Harvard of “serious failures” in four areas: antisemitism, racial discrimination, abandonment of rigor and viewpoint diversity. To become eligible for new grants, Harvard would need to enter negotiations with the federal government and prove it has satisfied the administration’s demands.

The administration has demanded a series of changes to campus policy, including reforms to crack down on protesters and pursue more viewpoint diversity among faculty.

In a letter Monday to Harvard’s president, Education Secretary Linda McMahon accused the school of enrolling foreign students who showed contempt for the U.S.

“Harvard University has made a mockery of this country’s higher education system,” McMahon wrote.

Harvard’s president has previously said he will not bend to government’s demands. The university sued to halt its funding freeze last month.

Harvard’s suit called the funding freeze “arbitrary and capricious,” saying it violated its First Amendment rights and the statutory provisions of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.

The Trump administration said previously that Harvard would need to meet a series of conditions to keep almost $9 billion in grants and contracts.

The school in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has an endowment of $53 billion, the largest in the country. Across the university, federal money accounted for 10.5% of revenue in 2023, not counting financial aid such as grants and student loans.

Education

New college grads face a tougher job market — again

This year’s new college graduates are heading into a tougher job market than last year’s — who had it worse off than the class before that — just as the Trump administration cracks down on student loan repayments.

Recent grads’ unemployment rate was 5.8% as of March, up from 4.6% a year earlier, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York reported last week. The share of new graduates working jobs that don’t require their degrees — a situation known as “underemployment” — hit 41.2% in March, rising from 40.6% that same month in 2024.

“Right now things are pretty frozen,” Allison Shrivastava, an economist at Indeed Hiring Lab, said of entry-level prospects. “A lot of employers and job seekers are both kind of deer-in-headlights, not sure what to do.”

Employers and job seekers are both kind of deer-in-headlights, not sure what to do.

Allison Shrivastava, economist, Indeed Hiring Lab

That squares with Julia Abbott’s experience.

“I just feel pretty screwed as it is right now,” said the psychology major who’s graduating this month from James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia. She said she’s applied to over 200 roles in social media and marketing, but “minimal interviews come out of it.”

Internship postings typically rise sharply in early spring, but they’re lagging 11 percentage points behind last year’s levels, Indeed said in April. The hiring platform sees demand for interns as a stronger gauge of new grads’ job prospects than entry-level postings, which increasingly target people with at least a few years’ experience.

In a worrying sign for the class of 2025, internship openings are “far below where they were in 2023 and 2022, when the labor market was exceptionally competitive,” Shrivastava said.

Young college grads have historically seen lower unemployment levels than the labor force overall, and they still do. But as The Atlantic pointed out Wednesday, this gap has narrowed to a record low, taking some of the shine off the traditional benefits of a bachelor’s degree.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration is restarting the “involuntary” repayment of federal student loans in default, a move that could sap money from paychecks, tax refunds, Social Security payments and disability and retirement benefits from millions of borrowers.

Repayments were paused during President Donald Trump’s first term in 2020 in response to Covid-19. The pandemic-era reprieve from forced collections ends Monday, just as a new TransUnion report finds a record share of federal student loan borrowers are 90 days or more past due and at risk of default — at 20.5% as of February, up 10 percentage points from five years earlier.

The debt crackdown comes as workers across the labor force confront a tougher hiring landscape. Employers added a better-than-expected 177,000 jobs in April, government data showed Friday, but analysts were quick to flag warning signs ahead.

Average pay growth has slowed to a crawl, and unemployment metrics indicate it’s taking longer for people looking for work to secure it. While the latest jobs numbers point to a “resilient” labor market, “we should curb our enthusiasm going forward given the backdrop of trade policies that will likely be a drag on the economy,” Olu Sonola, head of U.S. economic research at Fitch Ratings, said in a statement Friday. “The outlook remains very uncertain.”

The murky jobs forecast coincides with broader economic turbulence fueled by Trump’s ongoing trade war.

A slew of major companies have warned about tariff impacts in recent days. All but the wealthiest households are tightening their budgets, and consumer outlooks plunged to a 13-year low in a closely watched Conference Board survey released Tuesday. Some of the spending that is taking place reflects shoppers and businesses racing to make purchases before tariffs drive up costs for everything from cars to frozen fish and fireworks.

These headwinds are making many employers increasingly cautious about hiring young graduates.

Employers have pulled back plans to hire more new grads over just the last six months, according to a February and March survey by the National Association of Colleges and Employers, which polled major companies including Chevron, PepsiCo and Southwest Airlines. While most said their new-grad recruitment plans are holding steady, the share of respondents planning to expand entry-level hiring dipped to 24.6% this spring. That’s down from 27% last fall and the lowest rate since autumn 2020, during the depths of the pandemic.

In March, NACE released salary projections showing a mixed picture for the class of 2025, with social sciences graduates set to see a 3.6% drop in pay since last year, while agriculture and natural resources majors were on track for a 2.8% bump over their ’24 predecessors. The estimates, however, were based on employer survey data from last fall, weeks before Trump took office.

“I’m not surprised that new hiring is being restricted,” said Andy West, a senior partner at the consulting firm McKinsey who advises CEOs on corporate strategy and finance. He said some clients are increasingly discussing ways to “reallocate resources” amid tariffs and other macroeconomic worries, he said. As employers hunt for cost cuts and stability, many tend to zero in on expenses that fluctuate over time, including payrolls.

It just feels really scary, like walking into this world and not having something set out for me.

Julia Abbott, James Madison University, class of 2025

“When it comes to hiring and talent, often these are very short-term decisions around slowing down,” he said.

Class of ’25 job seekers are adjusting their expectations to the tighter market.

More than half have ditched the “dream job” plans they entered college with, according to a February survey by the grads-focused hiring platform Handshake. And 56% of current seniors are somewhat or very pessimistic about launching into the workforce right now. That’s about the same share as last year, but outlooks are down more sharply in fields like computer science, where over a quarter of seniors with that major voiced extreme pessimism.

Anxiety around landing a first full-time job is common among college students, but the deep uncertainty this year threatens to put a damper on commencement season.

“I can’t really celebrate my past four years,” said Abbott, the JMU senior. “It just feels really scary, like walking into this world and not having something set out for me.”

Education

Here’s what you need to know

The federal government on Monday will resume collecting defaulted student loan payments from millions of people for the first time since the start of the pandemic, officials said.

The Trump administration said it would collect the debt through a Treasury Department program that withholds payments through tax refunds, wages and government benefits.

The U.S. Education Department has not collected on defaulted loans since March 2020. Of the nearly 43 million people who owe money, only a little more than a third have made regular payments, the agency said.

In the last five years, student debt has grown to $1.6 trillion, officials said. Education Secretary Linda McMahon said taxpayers would now be saved from shouldering that cost.

“American taxpayers will no longer be forced to serve as collateral for irresponsible student loan policies,” McMahon said in an April 21 news release announcing the restart of collections.

The move comes after years of legal back-and-forth about loan forgiveness and at a time when advocates say student borrowers are stretched thin from inflation and growing concerns over the cost of living.

“We’re in the worst student loan landscape that we’ve ever been before,” said Sabrina Calazans, executive director of the Student Debt Crisis Center, a nonprofit that advocates for student debt cancellation.

“The plans and proposals being put forth by the Trump administration are going to harm millions of individuals and families,” Calazans added. “It’s going to create a financial catastrophe where folks will not be able to meet their basic needs.”

What happens now?

All borrowers in default should have received an email from the Office of Federal Student Aid alerting them to the changes.

Officials said the email urges borrowers to contact the Default Resolution Group to either make a monthly payment, enroll in an income-based repayment plan or sign up for loan rehabilitation — a process that can erase a default status if the borrower makes a set of payments during a specific time frame, depending on the type of loan.

To schedule monthly payments, borrowers who have not changed their marital status or income would have needed to send their most recent Federal 1040 tax return to the Education Department, according to instructions outlined on the Default Resolution Group’s website.

The Education Department said it will be using the Treasury Department’s Offset Program to collect on the debt by withholding payments through tax refunds, salaries and benefits like Social Security payments.

Under the program, the government can withhold entire federal tax refunds and up to 15% of a federal worker’s disposable pay. The government said the FSA would send notices about wage garnishment later this summer.

In an April opinion piece published in The Wall Street Journal, McMahon said borrowers who don’t make payments on time will see their credit scores go down, “and in some cases their wages automatically garnished.”

What happened to loan forgiveness?

Before leaving the White House in January, then-President Joe Biden announced his administration had canceled student debt for more than 5 million people, including many who attended schools that defrauded students, like DeVry University, as well as public service workers and those with total and permanent disabilities.

“Since Day One of my Administration, I promised to ensure higher-education is a ticket to the middle class, not a barrier to opportunity, and I’m proud to say we have forgiven more student loan debt than any other administration in history,” Biden said in a statement at the time.

In its April news release, however, Trump’s Education Department made it clear that “there will not be any mass loan forgiveness” going forward.

McMahon blamed the Biden administration for transferring hundreds of billions of dollars in debt to taxpayers and keeping borrowers in a “confusing limbo” about payments.

“The executive branch does not have the constitutional authority to wipe debt away, nor do the loan balances simply disappear,” she said.

Trump paused collection on most federal student loans in March 2020, and Biden continued to pause collection when he took office in 2021.

Biden had proposed allowing eligible borrowers to cancel up to $20,000 in debt until the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against his student loan debt relief plan in 2023. The plan would have cost more than $400 billion, and about 43 million Americans would have been eligible to participate.

In the Wall Street Journal op-ed, McMahon said Biden “never had the authority to forgive student loans across the board.”

She said resuming collections was not an act of unkindness to student borrowers but an act of fairness.

“Borrowing money and failing to pay it back isn’t a victimless offense. Debt doesn’t go away; it gets transferred to others,” she said. “If borrowers don’t pay their debts to the government, taxpayers do.”

-

Asia2 days ago

Asia2 days ago‘Operation Sindoor:’ Why India attacked Pakistan and conflict has escalated dramatically

-

Conflict Zones2 days ago

Conflict Zones2 days agoHow world leaders are reacting to India-Pakistan military strikes | Border Disputes News

-

Lifestyle2 days ago

Lifestyle2 days agoThe Met Gala is over, but dandyism isn’t. Here’s how to dress like a dandy in everyday life

-

Conflict Zones1 day ago

Conflict Zones1 day agoOperation Sindoor: What’s the significance of India’s Pakistan targets? | India-Pakistan Tensions News

-

Europe1 day ago

Europe1 day agoLive updates: New pope to be elected by the conclave

-

Middle East1 day ago

Middle East1 day agoWhat does the truce between the Houthis and the US mean for Yemenis? | Houthis

-

Africa1 day ago

Africa1 day agoKenya sentences four men for trying to smuggle ants out of the country

-

Africa1 day ago

Africa1 day agoBlack smoke from Sistine Chapel chimney signals no pope elected