London

CNN

—

There is something peculiar about entering a building only to be greeted by another one inside it, so it takes a moment to adjust upon arriving on the second floor of London’s prestigious Tate Modern art gallery. Directly in front of the entryway is a 1:1 scale facsimile of Do Ho Suh’s childhood home in Seoul, which he wrapped in mulberry paper and carefully traced in graphite to produce an intricate rubbing of the exterior. It is just one of many versions of home envisioned by the Korean artist over the past 30 years.

Running at Tate Modern through to October, “Walk the House” is Suh’s largest solo institutional show to date in the UK, where he has been based since 2016. Before that, he lived in the US, having studied at the Rhode Island School of Design and Yale University in the 1990s.

The exhibition’s name stems from an expression used in the context of the “hanok,” a traditional Korean house that can be taken down and reassembled elsewhere, thanks to its construction and lightweight materials. The buildings have become rarer over time, because of urbanization, war and occupation, which led to the destruction of many traditional homes in the country.

Suh’s own childhood home was an outlier amid Seoul’s changing cityscape during the 1970s, which underwent rapid development after the Korean War left the city in ruins. It spurred the artist’s ongoing preoccupations with home as both a physical space that could be dissolved and reanimated, but also a psychological construct that can reflect memory and identity.

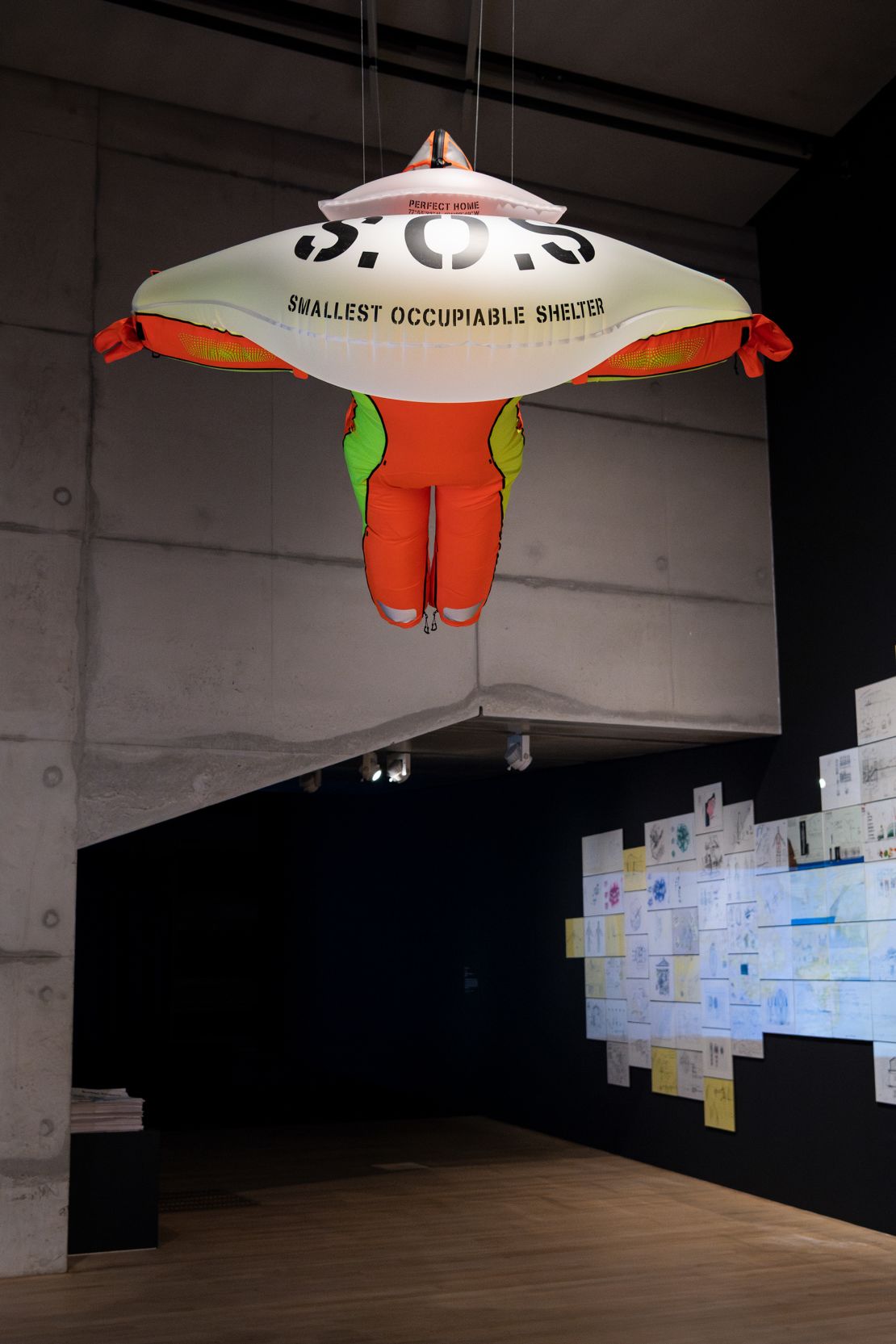

Among the show’s exhibits are embroidered artworks, architectural models in various materials and scales, and film works involving complex 3D techniques. The detailed outlines picked up in Suh’s hanok rubbing are echoed in two closely related large-scale pieces on display for the first time, both of which visitors can walk inside. “Perfect Home: London, Horsham, New York, Berlin, Providence, Seoul” (2024) takes various 3D fixtures and fittings from homes Suh has lived in around the world and maps them onto a tent-like model of his London apartment. “Nest/s” (2024) is a pastel-hued tunnel, again based on different places he has called home, this time splicing together incongruous hallways — an environment that holds symbolic meaning for the artist.

“I think that the experience of cultural displacement helped me to see these in-between spaces, the space that connects places. That journey lets me focus on transitional spaces, like corridors, staircases, entrances,” Suh told CNN at the show’s opening. The exhibition also features “Staircase” (2016), a 3D structure that was subsequently collapsed into a red, sinewy 2D tangle. “I think in general we tend to focus on destinations, but these bridges that connect those destinations, often we neglect them, but actually we spend most of our time in this transitional stage,” Suh said.

There’s a translucent quality to much of the work on display. Fine, gauzy textiles are used directly within many of the pieces, as well as in the form of a subtle room divider — the closest thing to an internal wall in the main space.

“For the first time since 2016, the galleries of the exhibition will have all their walls taken down in order to accommodate the multiple large-scale works that will be materialized within them, as well as the multiple times and spaces that those works carry,” said Dina Akhmadeeva, assistant curator for international art at Tate Modern, who co-curated the show with Nabila Abdel Nabi, senior curator of international art at the Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational. “In doing so, the open layout will form not a linear passage or narrative, but instead encourage visitors to meander, return, loop back, evoking an experience closer to the function of memory itself.”

Suh’s emphasis on spatial interventions poses creative challenges for curators as well as the institutions that hold these works. One such example is “Staircase-III” (2010), acquired by the Tate back in 2011, which often needs to be adapted to wherever it is shown by measuring new panels to fit each space. “I wanted to disturb the habitual experience of (encountering) an artwork in a museum,” said Suh by way of explanation. Akhmadeeva added that the approach challenged the “idea of permanence — of the work and of the space around it.”

Removing the gallery walls also reflects Suh’s interest in peeling environments back to their foundations. “It’s just the bare space that the architects originally conceived,” he said. Suh’s work often focuses on spatial experiences rather than material goods because, just like the rooms and buildings we inhabit, an empty space behaves like a “vessel” for memories, he explained. “Over the years and the time that you’ve spent in the space, you project your own experience and energy onto it, and then it becomes a memory.”

The artist does occasionally focus on ornaments and furnishings, however, as seen in his monumental film, “Robin Hood Gardens” (named after the East London housing estate it captures), which used photogrammetry to stitch together drone footage taken inside the council building awaiting demolition. It marked a rare instance of Suh documenting both residents and their belongings.

The film illustrates the subtle politics of Suh’s practice. “Often in my case, the color and the craftsmanship and the beauty in my work distract from the political undertone of it,” he said. Issues such as privacy, security, and access to space are intimately connected to class and public policy, but his commentary is covered in a soft veil of fabric or the gentle rub of graphite. The latter is also used in “Rubbing/Loving: Company Housing of Gwangju Theater” (2012), which reflects on the deadly Gwangju Uprising of 1980. The artwork resembles the shell of a room that is unravelled to form a flat, vertical structure, like a deconstructed box. It is based on a rubbing that was taken by Suh and his assistants while blindfolded — a nod to the censorship of the military’s violent response and its absence from South Korean collective memory.

The exhibition is bookended by pieces that address sociopolitical questions. “Bridge Project” (1999) explores land ownership among other issues, while “Public Figures” (2025), an evolution of a piece Suh made for the Venice Biennale in 2001, is a subverted monument featuring an empty plinth, directing focus to the many miniature figurines upholding it. For Suh, it was intended to address Korea’s histories of both oppression and resilience. While these two exhibits may feel distinct, for Suh, all of his work interrogates the boundaries between personal and public space, and the conditions that force transience or enable permanence.

The tension between public and private was thrown into sharp relief during the pandemic, when lockdowns forced people to spend most of their time indoors. Although Suh “scrutinized” all corners of his home during this time, the lockdowns didn’t materialize in his practice in the way one might expect. Instead, it elicited a more tender reflection on what is often the making of a home: people. It explains why, among the substantial, often colorful structures in the exhibition, there are two small tunics made for (and with) his two young daughters, adorned with pockets holding their most cherished belongings, such as crayons and toys.

“As a parent, it was quite a vulnerable situation. Other families, I cannot speak for them, but it really helped us to be together,” said Suh.