Lifestyle

Indigenous Catholics hope the next pope shares Francis’ approach to Native people

SIMOJOVEL, Mexico (AP) — At a recent service in the remote southern Mexican community of Simojovel, Catholic and Mayan symbolism mingled at the altar as the deacon — his wife beside him — read the gospel in his native Tsotsil and recalled Pope Francis’ teachings: work together for human rights, justice and Mother Earth.

The scene in the small church in Mexico’s poorest state, Chiapas, conveyed much of the message Francis delivered during his 2016 trip to the region and his other visits to far-flung locales, including the Amazon, Congo and the jungles of Papua New Guinea.

It also illustrated what the world’s Indigenous Catholics don’t want to lose with the death of the first pontiff from the Southern Hemisphere: their relatively newfound voice in an institution that once debated whether “Indians” had souls while backing European powers as they plundered the Americas and Africa.

“We ask God that the work (Francis) did for us not be in vain,” Deacon Juan Pérez Gómez told his small congregation. “We ask you to choose a new pope, a new servant, who hopefully Lord thinks the same way.”

Empowering Indigenous believers

Deacon Juan Pérez Gómez, left, takes part in a blessing ceremony after picking up Communion wafers that he will take to a priest to be consecrated before he can give them out in his next day service, in Nuevo Israelita, near Simojovel, Mexico, Saturday, April 26, 2025. (AP Photo/Isabel Mateos)

Francis was the first Latin American pope and the first from the order of the Jesuits, who are known for, among other things, their frontline work with society’s most marginalized groups. Although some feel Francis could have done more for their people during his 12 years as pontiff, Indigenous Catholics widely praise him for championing their causes, asking forgiveness for the church’s historical wrongs, and allowing them to incorporate aspects of their Native cultures into practicing their faith.

Among the places where his death has hit particularly hard are the lowlands of the Bolivian Amazon, which was home to Jesuit missions centuries ago that Francis praised for bringing Christianity and European-style education and economic organization to Indigenous people in a more humane way.

Marcial Fabricano, a 73-year-old leader of the Indigenous Mojeño people, remembers crying during Francis’ 2015 visit to Bolivia when the pope sought forgiveness for crimes the church committed against Indigenous people during the colonial-era conquest of the Americas. Before the visit, his and other Indigenous groups sent Francis a message asking him to push the authorities to respect them.

“I believe that Pope Francis read our message and it moved him,” he said. “We are the last bastion of the missions. … We can’t be ignored.”

That South American tour came shortly after the publication of one of Francis’ most important encyclicals in which he called for a revolution to fix a “structurally perverse” global economic system that allows the rich to exploit the poor and turns the Earth into “immense pile of filth.” He also encouraged the church to support movements defending the territory of marginalized people and financing their initiatives.

“For the first time, (a pope) felt like us, thought like us and was our great ally,” said Anitalia Pijachi Kuyuedo, a Colombian member of the Okaira-Muina Murui people who participated in the 2019 Amazon Synod in Rome, where Francis showed interest in everything related to the Amazon, including the roles of women.

Pijachi Kuyuendo, 45, said she hopes the next pope also works closely with Native people. “With his death, we face huge challenges.”

A wider path for the church

An Amazonian Indigenous child presents Pope Francis with a plant during the offertory of a Mass for the closing of the Amazon Synod in St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican, Oct. 27, 2019. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino, File)

Pérez Gómez, 57, is able to help tend to his small Tsotsil Catholic community in Mexico because the church restarted a deaconship program under Francis.

Facing a priest shortage in the 1960s, the church pushed the idea of deacons — married men who can perform some priestly rituals, such as baptisms, but not others, such as conducting Mass and hearing confession.

Samuel Ruiz, who spent four decades as bishop of San Cristóbal de las Casas trying to improve the lives of Chiapas’ Indigenous people, saw deaconships as a way to promote the faith among them and form what he called a “Native church.” The deaconship initiative was such a hit in Ruiz’s diocese, though, that the Vatican halted it there in 2002, worried that Ruiz was using it as a step toward allowing married priests and female deacons. The halt was lifted in 2014.

Pope Francis watches traditional dancers perform at the Martyrs’ Stadium In Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo, Feb. 2, 2023. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia, File)

Pérez Gómez, who waited 20 years before he was finally ordained a deacon in 2022, said he was inspired by Ruiz’s vision for a “Native church.” He said Francis reminded him of Ruiz, who died in 2011 and whom he credits with explaining the church’s true purpose to him as “liberator and evangelizer.”

“Francis also talked about liberation,” Pérez Gómez said, adding that he hopes the next pope shares that view.

New ways to celebrate Mass

Pope Francis holds hands with children wearing traditional costumes as he walks with Bolivian President Evo Morales upon his arrival at the airport in El Alto, Bolivia, July 8, 2015. The pouch Francis is wearing around his neck was given to him by Morales. It’s woven of alpaca with Indigenous trimmings and traditionally used by people in the Andes to hold coca leaves. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia, File)

It had been a half-century since the Vatican allowed Mass to be held in languages other than Latin when Francis visited Chiapas in 2016 and went a step further.

During a Mass that was the highlight of his visit, the Lord’s Prayer was sung in Tsotsil, readings were conducted in two other Mayan languages, Tseltal and Ch’ol, congregants danced while praying and Indigenous women stood at the altar.

Chiapas was a politically sensitive choice for the Pope’s visit, which wasn’t easily negotiated with the Vatican or Mexican government, according to Cardinal Felipe Arizmendi, who was then bishop of San Cristobal. In 1994, it saw an armed uprising by the Zapatistas, who demanded rights for Indigenous peoples.

Getting the Vatican to allow Mayan rituals in the Mass was also tricky, but Arizmendi recalled that there was a helpful precedent: Congo.

In 1988, the Vatican approved the first cultural innovation in a Mass, the so-called Zaire rite, which is a source of national pride and continental inclusion, said the Rev. Abbé Paul Agustin Madimba, a priest in Kinshasa. “It shows the value the church gives Africans.”

Francis cited the Zaire rite, which allowed some local music and dance to be incorporated into Mass, to argue for such accommodations with other Indigenous Catholics around the world.

The decision was made not only to expand Catholicism, which is in retreat in many places, “but also a theological act of deep listening and conversion, where the church recognizes that it is not the owner of cultural truth, but rather servant of the gospel for each people,” said Arturo Lomelí, a Mexican social anthropologist.

It was the Vatican’s way to see Indigenous rituals not as “threats, but rather as legitimate ways to express and live the faith,” he said.

‘No longer objects’

Pope Francis dons a headdress during a meeting with Indigenous communities, including First Nations, Metis and Inuit, at Our Lady of Seven Sorrows Catholic Church in Maskwacis, near Edmonton, Canada, July 25, 2022. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia, File)

On the Saturday after Francis’ death, Pérez Gómez stopped by a church in the town near his village to pick up the Communion wafers he would give out during his service the next day. Because he’s a deacon, he needs a priest to consecrate them for him ahead of time.

He and his wife, Crecencia López, don’t know who the next pope will be, but they hope he’s someone who shares Francis’ respect for Indigenous people. And they smile at the thought that perhaps one day, he could become a priest and she a deacon.

“We are no longer objects, but rather people” and that is thanks to God and his envoys, “jtatik Samuel (Ruiz)” and “jtatik Francis,” Pérez Gómez said, using a paternal term of great respect in Tseltal.

___

Associated Press writers Carlos Valdez in La Paz, Bolivia, Fabiano Maisonnave in Brasilia, Brazil, and Jen-Yves Kamale in Kinshasa, Congo contributed to this report.

Lifestyle

White House says Harvard will receive no new grants

WASHINGTON (AP) — Harvard University will receive no new federal grants until it meets a series of demands from President Donald Trump’s administration, the Education Department announced Monday.

The action was laid out in a letter to Harvard’s president and amounts to a major escalation of Trump’s battle with the Ivy League school. The administration previously froze $2.2 billion in federal grants to Harvard, and Trump is pushing to strip the school of its tax-exempt status.

Harvard has pushed back on the administration’s demands, setting up a closely watched clash in Trump’s attempt to force change at universities that he says have become hotbeds of liberalism and antisemitism.

In a press call, an Education Department official said Harvard will receive no new federal grants until it “demonstrates responsible management of the university” and satisfies federal demands on a range of subjects. The ban applies to federal research grants and not to federal financial aid that helps students cover college tuition and fees.

The official spoke on condition of anonymity to preview the decision on a call with reporters.

The official accused Harvard of “serious failures.” The person said Harvard has allowed antisemitism and racial discrimination to perpetuate, it has abandoned rigorous academic standards, and it has failed to allow a range of views on its campus. To become eligible for new grants, Harvard would need to enter negotiations with the federal government and prove it has satisfied the administration’s requirements.

The Trump administration has demanded that Harvard make broad government and leadership changes, revise its admissions policy and audit its faculty and student body to ensure the campus is home to many points of view.

The demands are part of a pressure campaign targeting several other high-profile universities. The administration has cut off money to colleges including Columbia University, the University of Pennsylvania and Cornell University, seeking compliance with Trump’s agenda.

The White House says it’s targeting campus antisemitism after pro-Palestinian protests swept U.S. college campuses last year. It’s also focused on the participation of transgender athletes in women’s sports. The attacks on Harvard increasingly have called out the university’s diversity, equity and inclusion efforts, along with questions about freedom of speech and thought by conservatives on campus.

In a letter Monday to Harvard’s president, Education Secretary Linda McMahon accused the school of enrolling foreign students who showed contempt for the U.S.

“Harvard University has made a mockery of this country’s higher education system,” McMahon wrote.

Harvard’s president has previously said he will not bend to the government’s demands. The university sued last month to halt the government’s funding freeze.

In a conversation with alumni last week, Harvard President Alan Garber acknowledged there was a “kernel of truth” to criticism over antisemitism, freedom of speech and wide viewpoints at Harvard. But he said the conflict with the federal government has become a threat to the school’s autonomy.

“We were faced with a recent demand from the federal government that, in the guise of combating antisemitism, raised new issues of control that frankly we did not anticipate, getting to the heart of governance,” Garber said. “We felt that we had to take a stand.”

Harvard’s lawsuit called the funding freeze “arbitrary and capricious,” saying it violated its First Amendment rights and the statutory provisions of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.

The Trump administration said previously that Harvard would need to meet a series of conditions to keep almost $9 billion in grants and contracts.

The school in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has an endowment of $53 billion, the largest in the country. Across the university, federal money accounted for 10.5% of revenue in 2023, not counting financial aid such as Pell grants and student loans.

Harvard isn’t alone in its reliance on federal money. Universities receive about 90% of all federal research spending, taking in $59.6 billion in 2023, according to the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics.

That accounts for more than half the $109 billion spent on research at universities, with most of the rest coming from college endowments, state and local governments and nonprofits.

To make up for the loss in federal funding, McMahon on Monday suggested Harvard rely on “its colossal endowment” and raise money from wealthy alumni.

Harvard generally steers about 5% of its endowment value toward university operations every year, accounting for about a third of its total budget, according to university documents.

The university could draw more from its endowment, but colleges generally try to avoid spending more than 5% to protect investment gains. Like other schools, Harvard is limited in how it spends endowment money, much of which comes from donors who specify how they want it to be used.

___

AP writer Adam Geller contributed reporting from New York.

___

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Lifestyle

Broadway producer Jeffrey Seller writes his autobiography, ‘Theater Kid’

NEW YORK (AP) — Jeffrey Seller, the Broadway producer behind such landmark hits as “Rent,” “Avenue Q” and “Hamilton,” didn’t initially write a memoir for us. He wrote it for himself.

“I really felt a personal existential need to write my story. I had to make sense of where I came from myself,” he says in his memento-filled Times Square office. “I started doing it as an exercise for me and I ultimately did it for theater kids of all ages everywhere.”

Seller’s “Theater Kid” — which he wrote even before finding a publishing house — traces the rise of an unlikely theater force who was raised in a poor neighborhood far from Broadway, along the way giving readers a portrait of the Great White Way in the gritty 1970s and ‘80s. In it, he is brutally honest.

“I am a jealous person. I am an envious person,” he says. “I’m a kind person, I’m an honest person. Sometimes I am a mean person and a stubborn person and a joyous person. And as the book shows, I was particularly in that era, often a very lonely person.”

This cover image released by Simon & Schuster shows “Theater Kid: A Broadway Memoir” by Jeffrey Seller. (Simon & Schuster via AP)

Seller, 60. who is candid about trysts, professional snubs, mistakes and his unorthodox family, says he wasn’t interested in writing a recipe book on how to make a producer.

“I was more interested in exploring, first and foremost, how a poor, gay, adopted Jewish kid from Cardboard Village in Oak Park, Michigan, gets to Broadway and produces ‘Rent’ at age 31.”

Unpacking Jeffrey Seller

It is the story of an outsider who is captivated by theater as a child who acts in Purim plays, directed a musical by Andrew Lippa, becomes a booking agent in New York and then a producer. Then he tracks down his biological family.

“My life has been a process of finally creating groups that I feel part of and accepting where I do fit in,” he says. “I also wrote this book for anyone who’s ever felt out.”

Jonathan Karp, president and CEO of Simon & Schuster, says he isn’t surprised that Seller delivered such a strong memoir because he believes the producer has an instinctive artistic sensibility.

“There aren’t that many producers you could say have literally changed the face of theater. And I think that’s what Jeffrey Seller has done,” says Karp. “It is the work of somebody who is much more than a producer, who is writer in his own right and who has a really interesting and emotional and dramatic story to tell.”

The book reaches a crescendo with a behind-the-scenes look at his friendship and collaboration with playwright and composer Jonathan Larson and the making of his “Rent.”

Seller writes about a torturous creative process in which Larson would take one step forward with the script over years only to take two backward. He also writes movingly about carrying on after Larson, who died from an aortic dissection the day before “Rent’s” first off-Broadway preview.

“‘Rent’ changed my life forever, but, more important, ‘Rent’ changed musical theater forever. There is no ‘In the Heights’ without ‘Rent,’” Seller says. “I don’t think there’s a ‘Next to Normal’ without ‘Rent.’ I don’t think there’s a ‘Dear Evan Hansen’ without ‘Rent.’”

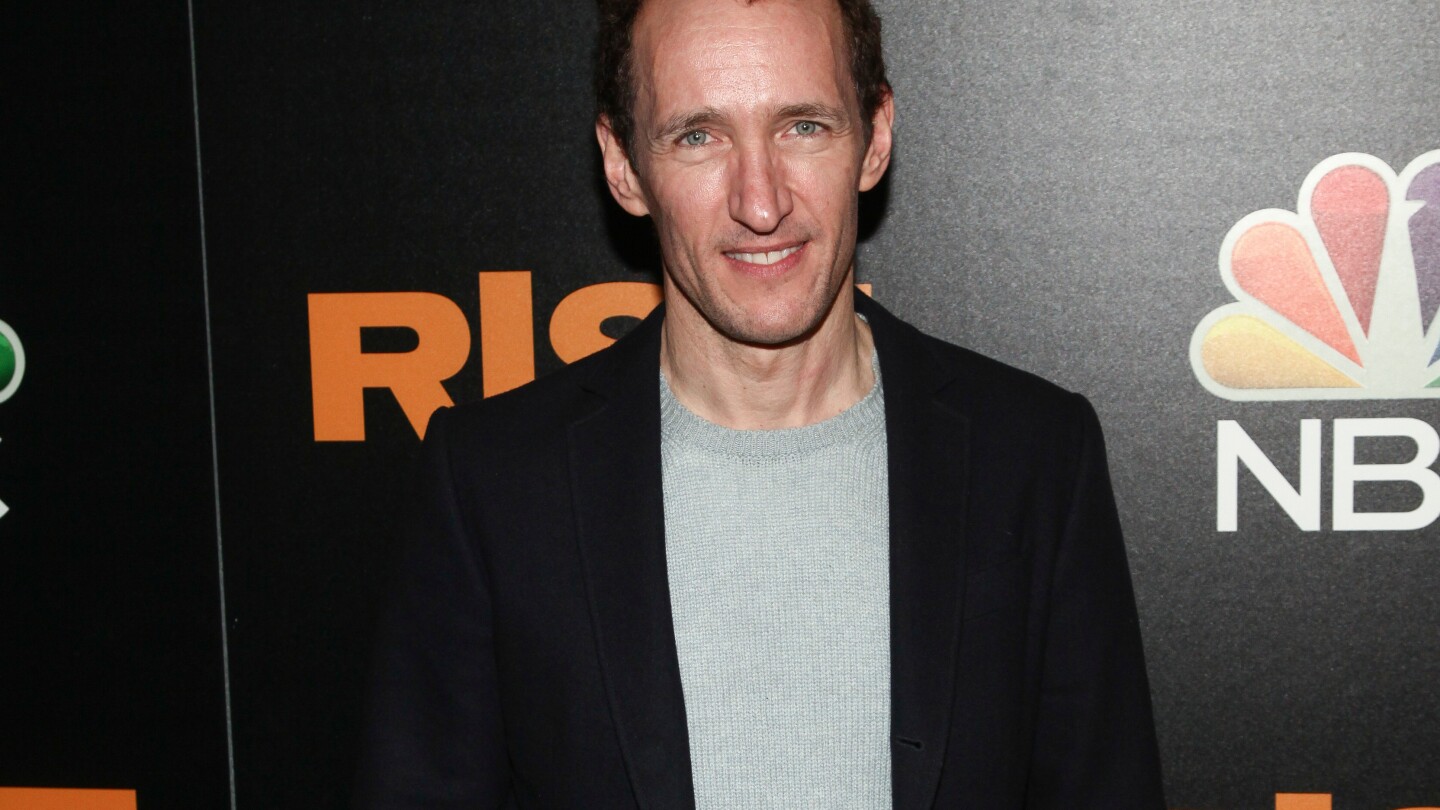

“Hamilton” producer Seller accepts the award for best musical at the Tony Awards in New York on June 12, 2016. (Photo by Evan Agostini/Invision/AP, File)

What about ‘Hamilton’?

So enamored was Seller with “Rent” that he initially ended his memoir there in the mid-’90s. It took some coaxing from Karp to get him to include stories about “Avenue Q,” “In the Heights” and “Hamilton.”

“‘Hamilton’ becomes a cultural phenomenon. It’s the biggest hit of my career,” Seller says. “It’s one of the biggest hits in Broadway history. It’s much bigger hit than ‘Rent’ was. But that doesn’t change what ‘Rent’ did.”

In a sort of theater flex, the memoir’s audiobook has appearances by Annaleigh Ashford, Danny Burstein, Darren Criss, Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Renée Elise Goldsberry, Lindsay Mendez, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Andrew Rannells, Conrad Ricamora and Christopher Sieber. There’s original music composed by Tony- and Pulitzer Prize-winner Tom Kitt.

The portrait of Broadway Seller offers when he first arrives is one far different from today, where the theaters are bursting with new plays and musicals and the season’s box office easily blows past the $1 billion mark.

In 1995, the year before “Rent” debuted off-Broadway, there was only one Tony Award-eligible candidate for best original musical score and the same for best book — “Sunset Boulevard.” This season, there were 14 new eligible musicals.

“I think that’s just such a great moment in Broadway history to say, ‘This is before ’Rent,’ and then look what happens after. Not because ‘Rent’ brought in an era of rock musicals, but it opened the doors to more experimentation and more unexpected ideas, more variety.”

He is drawn to contemporary stories with modern issues and all four of his Tony wins for best musical are set in New York.

“For me, shows that were about people we might know, that were about our issues, about our dreams, about our shame, about things that embarrass us — that’s what touched me the most deeply,” he says. “I was looking to have the hair on my arms rise. I was looking to be emotionally moved.”

Lifestyle

Not debate, ‘Ethics Bowl’ helps show students a new world of discourse

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. (AP) — A contrast:

At the National Speech and Debate Tournament, two high school students take the stage. The first articulates the position he has been assigned to defend — people should have a right to secede from their government — and why it is correct. Another student, assigned the opposite position, begins to systematically tear down her opponent’s views.

A year later and 800 miles away, two teams of high school students convene at the University of North Carolina for the National High School Ethics Bowl finals. A moderator asks about the boundaries of discourse — when a public figure dies, how do you weigh the value and harm of critical commentary about their life?

Teams have not been assigned positions. One presents their ideas. The opposing team asks questions that help everyone to think about the issue more deeply. No one attacks.

Many a young debater may learn the rhetorical skills to become a successful lawyer or politician, subduing an opponent through wit and wordplay. But are they learning skills that will make them better citizens of an increasingly complex and contentious republic?

In an age when many Americans are wondering whether it is still possible to have a principled, respectful disagreement over important issues, proponents of Ethics Bowl say it points the way.

Discussion replaces contentiousness

Ethics Bowl may resemble debate. After all, it’s two teams discussing a controversial or difficult topic. But they are very different.

In Ethics Bowl, teams aren’t assigned a specific position on an issue that they have to defend regardless of their beliefs. Instead, members are given cases to discuss and make their own decisions about what they consider the best position. Teams can, and often do, come to similar conclusions. It is — and this is important — OK for them to agree. Scoring is based on how deeply they explore the issues, including other viewpoints.

Robert Ladenson, who developed the Ethics Bowl as a college philosophy classroom exercise back in 1993 and went on to lead the Intercollegiate Ethics Bowl for decades, explains what he considers an ethical understanding of an issue in an oral history for the University of Illinois in 2023.

It means “having some capacity to view, from the inside, the ethical outlooks of people who disagree with you. That means not simply being aware of what they’ve said or what they’ve written, or being able to develop a nifty debaters’ responses to the viewpoints they hold — but really looking inside the other view and trying to understand it from the other person’s way of looking at the world.”

It’s a reach for understanding and common ground

That plays out at Ethics Bowl. Take the case “See Spot Clone,” about whether it is ever ethical to clone a beloved pet.

Harpeth Hall from Nashville starts the discussion with six minutes to present their thoughts. There are millions of homeless pets, so the ethical choice is to adopt, they believe. Cloning is self-serving for the human. The pet cannot consent to being cloned. Also, cloning may involve unknown health issues for the cloned pet, as in the renowned case of Dolly the sheep. The team also believes that death is a part of life, and it is important for people to confront death.

Now it is the turn of team B, Miami’s Archimedean Upper Conservatory — not to attack and refute, but to ask questions that expand the discussion. What about pet breeders? Where do they fit on the ethical continuum? Also, what’s so wrong with cloning a pet for your own happiness? Are all selfish pursuits bad?

Team A responds that breeding is better than cloning but worse than adopting a stray. They point out that a cloned pet will not have the same personality, and that could bring the owner pain instead of comfort.

Next the judges ask questions. What if there were no possible health problems for the cloned animal? What if the animal is not cloned to comfort an owner but for a more noble purpose? Would it be ethical to clone a skilled search-and-rescue dog?

Cloning is still a threat to the “natural cycle of life,” Team A contends. And there is no guarantee that the temperament and personality that make an excellent service animal would be retained in a clone.

Once the round is complete, the moderator introduces a new case.

Easy answers are avoided

In a society awash in shortcuts and simple solutions, simply setting the ground rules for contentious conversations can be a high hill to climb. At the Ethics Bowl, though, it’s part of the point: The process of conversation is as important as the outcome. And subtlety matters.

A good Ethics Bowl case is one where “two well-meaning individuals can take in all of the same facts and information and come to diametrically opposite, value-driven answers,” says Alex Richardson, who directed the National Bowl for five years.

The cases students grapple with include real-life scenarios pulled from the headlines, like the less-than-respectful response to the murder of United Healthcare CEO Brian Thompson. There are also more philosophical issues, like whether humans should pursue immortality. And there are dilemmas that teenagers deal with every day, like whether not posting on Instagram about a hate crime in your community makes you complicit.

That last case was a difficult one for the team from Harpeth Hall, they say, but it helped them clarify some of their thoughts around social media.

“We came to the conclusion that no one is obligated to share information,” says Katherine Thomas. “But then there was a difference like when you’re talking about Taylor Swift, when she actually could register 500,000 people to vote but she decides not to. Is she actually complicit in that? She has the actual power to make change, where I don’t, really, with my 200 followers.”

Another case considered whether to confront an uncle who makes sexist remarks at the dinner table. Discussing the issue with her Harpeth Hall teammates helped Thalia Vidalakis think through when it might be good to speak up and when “it’s good to just be there for your family and recognize that there’s going to be differences.”

It unfolds in a low-key way

A group of teenagers sits at a table with sticker-covered water bottles and the occasional Red Bull. They are allowed only pens and blank paper, no previous notes, but their backpacks litter the room. Their opponents sit at a neighboring table. In between is a moderator. Facing them are three judges pulled from the UNC philosophy department, Ethics Bowl leaders from other states, even the community at large. There is no dress code, so the teens come in whatever they consider nice clothes.

The teams have been discussing a group of cases for weeks, but they don’t know which they’ll be asked about. Once the question is read, they are given a few minutes to discuss. That’s when one or two of the teammates generally scurry around the table to huddle. Intense whispering and furious scribbling ensue.

It’s clearly a contest. There is a winning team and a trophy. But students say it is not competitive in a traditional sense.

“We’re all sad that it has to end. But I agree that it’s not about beating people,” says Lizzie Lyman, whose first-year team from Midtown High School in Atlanta lost in the semifinals of the national championship. “When it becomes about winning and beating the other team, it gets hostile and … just unsavory. When it’s about constructively answering a question and just having a really interesting, engaging conversation, that’s where you get to have all these amazing conversations.”

Competitiveness isn’t only beside the point. It can even be counterproductive in achieving the desired goal. That’s how Mae Bradford of the winning team BASIS Flagstaff from Arizona sees it. Her assessment: “Something that’s rare and unique about Ethics Bowl is that those who don’t focus on winning and instead focus on truth and respect and getting to the moral heart of the issue will win.”

Changing minds, one kid at a time

Part of the point of the Ethics Bowl is to create well-rounded students who ingest other viewpoints and engage without arguing. A 2022 survey of participants in nationals found that 100% believed that their critical thinking skills had improved. A large majority said their ethical or political beliefs had changed.

There is clearly a thirst for a different kind of competition. The National High School Ethics Bowl is only 12 years old, and this year saw 550 teams competing in regional bowls around the country.

Sona Zarkou, also on the BASIS Flagstaff team, sees herself as a case study in Ethics Bowl benefits. When she practiced debate, she says, she was “kind of a jerk” — “very quick to attack and very rude” about opposing views. In Ethics Bowl she sees herself “turn the discussion to something a lot more respectful, a lot more truth-oriented.”

Rhiannon Boyd, a judge at this year’s competition as well as a high school teacher and coach and the organizer of the Virginia High School Ethics Bowl, has seen the positive changes as well. Two of her students last year were on opposite ends of the political spectrum. Their disagreement was great. Could they be on the same team together? In the end, both joined and made it all the way to nationals.

Their differing opinions remain. But now, Boyd says, they are “really good friends.”

“They can see each other’s strengths because they were sitting side by side at nationals in a huddle trying to build off of each other’s ideas,” she says. “They could see that leveraging those differences was actually the thing that made them strong.”

Ethics Bowl: Lesson learned. ___

AP National Writer Allen G. Breed contributed to this report.

-

Europe2 days ago

Europe2 days agoTrump draws criticism with AI image of himself as the pope ahead of the papal conclave

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoPeople close to the fan who fell onto field at PNC Park share positive update

-

Middle East2 days ago

Middle East2 days agoCanelo Alvarez beats Scull to reclaim undisputed super-middleweight title | Boxing News

-

Europe2 days ago

Europe2 days agoUkraine claims it destroyed Russian fighter jet using seaborne drone for the first time

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoRoger Clemens: Red Sox great watches son Kody hit Fenway Park home run – for the Minnesota Twins

-

Europe2 days ago

Europe2 days agoVenice is sinking. Now there’s a radical plan to lift the entire city above rising floodwaters

-

Europe1 day ago

Europe1 day agoFather of crypto entrepreneur rescued from kidnappers after having finger severed

-

Middle East2 days ago

Middle East2 days agoIsraeli soldiers, settlers harass Palestinian activist featured in BBC film | Israel-Palestine conflict News