Middle East

After Israel’s bombs, Nabatieh’s Monday Market revives itself once again | Israel attacks Lebanon

Nabatieh, Lebanon – It is a bitterly cold February morning, and Sanaa Khreiss tugs her cardigan tighter as she begins unloading her van.

The sharp bite of early spring has kept most people away from the Nabatieh souk, but not Sanaa and her husband, Youssef.

The market is quiet as the sun breaks through the grey clouds, except for a few vendors setting up.

Sanaa, who has sold at this spot for the past four years, moves with the calm precision of someone who has perfected her craft over time.

She arranges the lingerie she sells, piece by piece, carefully lining them up, each addition bringing a touch of colour and vibrancy to her stall.

The soft murmur of voices grows as more vendors arrive, helping each other set up canopies to shield their stalls from potential rain.

The task is far from easy. The wind tugs at the fabric, and some canopies still hold water from the recent rainfall. But they press on, and slowly, the white shapes pop up, and Nabatieh’s Monday Market has started.

Sanaa smiles at the occasional passer-by, her warmth never fading. She has come to know many by name and can anticipate their requests. Her voice is quiet but inviting.

“I choose the Monday Market because there’s always a lot of movement, and it’s a historic, popular spot in the south,” Sanaa tells Al Jazeera, her fingers brushing over lace and satin as she unpacks more items from the van.

In the stall next door, her husband Youssef works in silence. His movements are precise, almost meditative, but there is a hint of tension in how he arranges the containers and cookware.

Youssef has never imagined himself here; he used to be a driver for the Khiam municipality, but lost his job when the municipality ceased operations after the outbreak of the Israeli war on Lebanon in 2023, which particularly devastated Lebanon’s south, including Nabatieh, one of the region’s biggest cities.

Since then, Youssef has quietly adapted to the life of a vendor beside Sanaa.

Youssef is quiet and reserved, a stark contrast to Sanaa’s extroverted warmth. He focuses intently on his tasks, but when approached by a customer, his blue eyes shine with welcome, and his voice is friendly.

At first glance, no one would guess the weight those eyes carry – war, displacement, losing his livelihood and their home in Khiam. But at the market, it is business as usual.

The market

Shoes, toys, spices, clothing, books, food, electronics, and accessories – the Monday Market sells all that and more.

The Monday Market in Nabatieh has its roots in the late Mamluk era (1250–1517 AD) and continued to thrive under Ottoman rule. Along with the Souk of Bint Jbeil and the Khan Market in Hasbaiyya, it is one of the oldest weekly markets in south Lebanon, established as part of efforts to extend trade routes across the region.

Back then, traders moved between Palestine and Lebanon, transporting goods by mule and donkey over rough, slow roads. Nabatieh’s location made it a natural stop – a bustling centre where merchants from nearby villages would gather to buy, sell and rest before continuing their journeys. The market also sat along a wider network of internal pilgrimage routes, connecting Jerusalem to Damascus, Mecca and Najaf.

Nabatieh Mayor Khodor Kodeih recounts that merchants travelling between Palestine and Lebanon would stop at a “khan” – an inn that also served as a trading centre – on the site of the current market.

A khan typically featured a square courtyard surrounded by rooms on two levels, with open arcades. Merchants would rest, trade and display their goods there, gradually transforming the site into the bustling Monday Market.

Over time, the market has become more than just a place to buy and sell – it is a ritual that stitches together the social and economic fabric of southern Lebanon.

The area around the old khans expanded into a larger open-air souk. Israeli air strikes during the last war destroyed the original khans, but traces of the market’s past still remain. Today, the Monday Market spans three to four city blocks in central Nabatieh, surrounded by remnants of Ottoman-era architecture. While shops remain open throughout the week, the market itself is made up of temporary stalls and stands that operate only on Mondays.

Before Israel’s recent war on Lebanon, the market filled the streets, framed by Ottoman-era buildings with wooden shutters and iron balconies. Merchants packed the narrow alleys with vibrant goods, their calls for business filling the air. But on November 13, 2024, Israeli air strikes reduced the historic market to rubble. Stone arches crumbled, shopfronts burned, and what was once a bustling hub was left in ruins.

All that remains

Arriving at Sultan Square, the usual site of the old market, one is left confused. All that remains is a vast, empty space at the heart of the city.

The famous Al-Sultan sweet shop, after which the square was named, is gone. Nearby, other sweet shops – including al-Dimassi, established in 1949 and central to Nabatieh’s culinary identity and reputation – are also missing. They once sold staples of Lebanese dessert culture: baklava, nammoura, maamoul, and during Ramadan, seasonal treats like kallaj and an all-time favourite, halawet el-jibn.

Every market morning, merchants sweep the streets, using only brooms to push the debris to the sides and clear space for their stalls. Even as the wind blows rubble back towards their stand, they keep sweeping, determined to maintain a neat and orderly market.

Sanaa remembers the high-end lingerie shops that once competed with her; they’re gone too, reduced to debris amid which vendors have set up their tents as they wait for the municipality to clear the area.

There should be more vendors on that cold morning, but the rain and war have changed things.

“The good thing about rainy days,” Sanaa jokes, “is that there are fewer merchants, so customers have limited options.”

Before the war, she sold in bulk – new brides buying trousseaus, women stocking up. Now, purchases are small and careful – with homes and livelihoods lost, shopping is for necessity, not luxuries or impulse buys.

On a typical Monday, the market runs from 5am to 5pm. Merchants arrive early, making their way to their designated spots, some on the pavement, others against a backdrop of a collapsed building.

Vegetable vendors lay their produce out in large sacks and plastic crates. Normally, the market is so crowded with people that cars can’t pass and visitors have to squeeze past each other from one stall to the next.

Though profits aren’t what they used to be, Sanaa is just happy to be back. She’s kept her prices the same, hoping the market will rebound.

“This is the most important market in the south,” she says. “And we need to follow the source of our livelihood.”

‘Deep love story with the Monday market’

Next to Sanaa’s stall is Jihad Abdallah’s, where he has rigged up several racks to hang his collection of women’s sports clothes.

Yesterday’s snow is melting as the sun comes out, but Jihad keeps his hoodie up, still feeling the lingering cold.

Customers have started trickling over, but it isn’t enough to shake the frustrated, tired look on his face.

Jihad, from the border village of Bint Jbeil, spends his week travelling between different town markets in southern Lebanon to make ends meet.

He was among the first to set up in Bint Jbeil’s Thursday Market as soon as the ceasefire with Israel was announced on November 27, 2024. Jihad didn’t have many options. Bint Jbeil was the market he knew best – he memorised the rhythms, understood customer demands, and recognised how to turn profit. Still, business was slow.

“In Bint Jbeil, the market needs time to recover because many residents from nearby villages, like Blida, Aitaroun and Maroun al-Ras, haven’t returned yet,” Abdallah tells Al Jazeera.

“However, in Nabatieh, nearby towns have seen more returnees.”

Jihad was also among the first to return to the Nabatieh market, joining the very first band of merchants in clearing as much debris as they could manage.

“The Israelis want to make this land unliveable, but we’re here. We’re staying,” Jihad says. “They destroyed everything out of spite, but they can’t take our will.”

Further down the road, Abbas Sbeity has set up his stand of clothes for the day, a collection of children’s winter clothes he couldn’t sell because of the war.

“I had to empty my van to make room for mattresses for my kids to sleep on when we first escaped Qaaqaait al-Jisr [a village near Nabatieh],” he tells Al Jazeera, pointing to the van behind him, now packed with clothes.

Abbas is trying to make a profit, however small, from clothes that were meant to be sold when children returned to school last fall.

He’s been coming to the Monday Market for 30 years, a job passed down from his father, who inherited it from his grandfather.

“My grandfather used to bring me here on a mule!” he says with a nostalgic smile. For a moment, he stares off, lost in thought. His smile stays, but his voice holds a trace of sadness.

“There’s a deep love story with the Monday Market,” he adds. “But now, there’s a sadness in the air. People’s spirits are still heavy, and the destruction around us really affects their morale.”

Abbas remembers how people came not only to buy but to hang out for a weekly outing they could count on for fun, no matter the weather. Even if they didn’t buy anything, they’d enjoy the crowds or grab a bite, whether from the small shops selling manouches, shawarma, kaak or falafel sandwiches, or from a restaurant nearby, from local favourites like Al-Bohsasa to Western chains.

Many would also stop by Al-Sultan and Al-Dimassi, which were the closest to the market, to enjoy a sweet treat, a perfect way to top off their visit.

By noon, the rain had stopped, leaving behind a gloomy day as the sun struggled to break through the clouds, casting a faint light over the market. People haggled over prices, searched for specific sizes, and despite the changes brought by war, the Monday Market pressed on, determined to hold on to its place.

‘We won’t let them,’ determination versus reality

At one end of the Sultan Square, near the upper right corner, a half-destroyed building still stands where vendors used to set up shop before the war. Now, produce vendors arrange their stalls beneath it as if nothing had changed. The remnants of the structure loom above them – fragments of walls hanging precariously, held together by stray wires that look ready to snap.

Yet the vendors paid no mind, too absorbed in tending to customers. The building’s arched openings and ornate details, though battered, still hinted at the city’s rich past. Its verandas, standing like silent witnesses to the souk below, bore testament to both the scars of war and a culture that refused to disappear.

At the far end of the market, by the main road leading out of Nabatieh to nearby villages, one cart stands alone, piled high with nuts and dried fruits. Its owner adds more, making the stacks look like they might spill over at any second.

Roasted corn, chickpeas, and almonds sit next to raw almonds, hazelnuts, cashews and walnuts. Dried fruits are displayed front and centre, dates and apricots taking the spotlight.

At the back of the cart, Rachid Dennawi arranges candies – gummy bears and marshmallows in all shapes and flavours. It’s his first day back at the Monday Market since the war began.

Abir Badran, a customer dressed in a dark cardigan and a long black scarf that gently frames her face, is the first to reach Rachid’s cart while he’s still setting up. Her face lights up as she leans in to examine the dates, carefully picking through them.

“Finally, you’re back!” she says, reaching for the dates – they’re bigger and better than what she can find at other places, she says.

Rachid, originally from Tripoli in Lebanon’s north, makes the three-hour journey to Nabatieh because he believes the market is livelier, has more customers.

Over time, Rachid has built a loyal clientele, and people like Abir swear by his dried fruit and nut mix.

“The people here are different,” he tells Al Jazeera, handing Abir a handful of almonds to taste. “They don’t just buy from you – they welcome you and want you to succeed.”

But Abir didn’t just come to stock up – she is there because the Monday Market has become an act of resistance.

“The Israelis want to sever our ties to this land,” Abir tells Al Jazeera. “But we won’t let them.”

While the optimism is clear, the reality on the ground is tough.

Merchants and residents are doing what they can with what they have. Some have relocated their shops or started new businesses, but some are stuck in limbo.

Mayor Kodeih estimates it will take at least two years to rebuild the market and is critical of the Lebanese government’s support.

“We will restore the market,” he says. “It won’t be the same, but we’ll bring it back.”

The mayor was injured in the Israeli strike on the municipality in mid-October, which killed 16 people; he is one of the two survivors.

It is not easy to leave the market behind – or Nabatieh.

Despite the destruction, the city hums with life: Shops are open, cafes are busy, and people lean in doorways, greeting passers-by with warm smiles and easy conversation.

The gravity of war has left its mark. The destruction is visible at every turn – a bookshop reduced to rubble, shops flattened to the ground – but it has not stripped away the city’s kindness or its sense of humour.

In front of a lot with nothing more than a gaping hole in it, a playful banner by the shop that used to stand there reads: “We’ll be back soon … we’re just redecorating.”

One of the paths out of the Sultan Square leads visitors northeast, into a quieter neighbourhood of cobbled streets, where cafes and small shops line the way. Here, people sip coffee and linger by storefronts, seemingly untouched by the devastation only steps away.

Turning back at the boundary between the two, the destruction that has decimated the market is more apparent, as is the loss to Nabatieh and southern Lebanon.

The market’s heyday will live on only in the memories of those who experienced it, younger generations will never have that same experience.

Middle East

Children among several killed in Israel’s attacks on Gaza amid aid blockade | Israel-Palestine conflict News

Seven people, including three children, have been killed in Israeli attacks on the Gaza Strip amid a months-long Israeli blockade that has deepened the humanitarian crisis in the war-torn coastal enclave.

Palestinian news agency Wafa said Israeli warplanes bombed a tent in the Sabra neighbourhood of Gaza City on Saturday morning, killing five members of the Tlaib family.

“Three children, their mother and her husband were sleeping inside a tent and were bombed by an [Israeli] occupation aircraft,” family member Omar Abu al-Kass told the AFP news agency.

The strikes came “without warning and without having done anything wrong”, added Abu al-Kass, who said he was the children’s maternal grandfather.

In parallel, a drone attack on Gaza City’s Tuffah neighbourhood left one person dead.

Further south, Wafa said Israeli gunboats opened “heavy fire” on the shores of Rafah, killing a man identified as Mohammed Saeed al-Bardawil. Two more civilians were injured in an attack on the al-Mawasi humanitarian zone, west of Rafah.

In the past 24 hours, at least 23 Palestinians have been killed and 124 others injured in Israeli attacks across the Gaza Strip, according to the enclave’s Health Ministry.

Israeli blockade

The attacks came amid Israel’s continuing refusal to allow vital supplies into Gaza since March 2, leaving the enclave’s 2.3 million residents dependent on a dwindling number of charity kitchens, which have been shutting down in recent days as food runs out.

Reporting from Deir el-Balah in central Gaza, Al Jazeera’s Hind Khoudary said: “There’s barely food … We’re talking about bakeries not operating, we’re talking about zero distribution points and we’re talking about only a few hot meal kitchens still operating.”

Khoudary said people queueing for hours would often leave empty-handed, with remaining kitchens stretching out food that would previously have fed 100 to serve up to 2,000 people.

“We’re seeing more people dying, we’re seeing more children dying due to malnutrition and the lack of food. But it’s not only the lack of food, it’s also the lack of medical supplies, it’s the lack of fuel, cooking gas and it’s the lack of everything,” she said.

Among the charities shuttering operations, the United States-based World Central Kitchen said on Wednesday that it had been forced to close down because it no longer had supplies to bake bread or cook meals.

The United Nations’ Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs appealed for the blockade to be lifted.

“Children are starving, and dying. Community kitchens are shutting down. Clean water is running out,” it said on Friday in a post on X.

‘Failure of humanity’

The blockade is also having a devastating effect on people with chronic illnesses, depriving Palestinians who suffer from diabetes, cancer and rare conditions, of life-saving medication.

Reporting from Gaza City, Al Jazeera’s Hani Mahmoud said: “Doctors here say the tragedy is not in what’s happening, but in what is preventable.”

“These diseases have a treatment, but people of Gaza no longer have access to them, and they say that this is not just a failure of logistics, but of humanity,” he added.

Mahmoud spoke to the father of a 10-year-old boy suffering from diabetes, who said insulin was not available across northern Gaza.

“I spend entire days searching pharmacies, hoping to find it. Sometimes we hear that individuals might have it, so I go to their homes to barter,” he said.

Said al-Soudy, head of emergency in the oncology department of Gaza City’s Al Helou International Hospital, told Al Jazeera: “A large part of patients are struggling to find their essential medications. Without them, their health conditions deteriorate and may become life-threatening.”

Pharmacist Rana Alsamak told Al Jazeera that Palestinians were unable to obtain medication for “multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, hepatitis, chronic illnesses and … immune-related diseases”.

“These conditions now go largely untreated,” she said.

On Friday, the United States said it was establishing the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation to coordinate aid deliveries into Gaza, with Israel providing military security for operations. The United Nations rejected the move, saying it would weaponise aid, violate principles of neutrality and cause mass displacement.

Middle East

Iraq look to former Australia coach Arnold to boost 2026 World Cup hopes | Football News

Iraq replaces Jesus Casas as head coach with former Australia boss Graham Arnold ahead of crunch World Cup qualifiers.

Former Australia manager Graham Arnold has been confirmed as the new head coach of Iraq by the country’s football federation ahead of next month’s World Cup qualifiers against South Korea and Jordan.

Arnold’s appointment was announced on social media by the Iraq Football Association, which published photographs of the 61-year-old being welcomed in Baghdad by officials from the national body.

“We are delighted to announce Graham Arnold as the new head coach of the Iraq national team,” the federation said in a post on Instagram. “Welcome to the Lions of Mesopotamia!”

Arnold replaces Jesus Casas at the helm after the Spaniard’s departure in the wake of a 2-1 loss to Palestine in March during the third round of Asia’s qualifiers for the 2026 World Cup.

That result left the Iraqis in third place in the standings in Group B, four points adrift of leaders South Korea and one behind the Jordanians.

Welcome to Baghdad ✔️

Our new Australian head coach Graham Arnold has arrived in the Iraqi capital! 🛬 pic.twitter.com/AH1IybroHv

— Iraq National Team (@IraqNT_EN) May 9, 2025

The top two finishers in each of Asia’s three qualifying groups advance automatically to the World Cup, while the teams in third and fourth place progress to another round of preliminaries.

Arnold’s first game in charge will be in Basra on June 5 against the South Koreans before he takes his new team to Amman to face Jordan five days later. Iraq are attempting to qualify for the World Cup for the first time since 1986.

The appointment sees Arnold return to international management more than seven months after standing down as Australia’s head coach.

Arnold, who led the Australians to the knockout rounds of the 2022 World Cup during a six-year spell in charge, quit after an uninspired start to the current phase of qualifying when his side lost to Bahrain and drew with Indonesia in September.

He was replaced by Tony Popovic, the former Western Sydney Wanderers coach who has taken the Socceroos to second place in Group C of Asia’s qualifiers ahead of games against already qualified Japan and Saudi Arabia in June.

Middle East

Netanyahu’s war choices fuel discord in Israel over captives’ fate in Gaza | Israel-Palestine conflict News

To prioritise the release of the captives in Gaza, or to continue fighting what critics are calling Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s “forever war” – that is the question increasingly dividing Israel.

Israel’s government, laser-focused on the idea of a total victory against Hamas in Gaza, appears to be opting for the latter.

And that is only increasing the criticism Netanyahu has received since October 2023, firstly for his government’s failure to stop the October 7 attack, and then for failing to end a now 19-month war, or provide a clear vision for what the “day after” in Gaza will look like.

Netanyahu’s decision in March to unilaterally end a ceasefire instead of continuing with an agreement that would have brought home the remaining captives has widened the cracks within Israeli society, as opponents realised that the likelihood of the captives leaving Gaza alive was becoming more remote.

In recent weeks, a wave of open letter writing from within military units has emerged protesting the government’s priorities.

The discontent has also gained traction with the public. Earlier this month, thousands of Israelis gathered outside the Ministry of Defence in Tel Aviv to protest against Netanyahu’s decision to call up a further 60,000 reservists as part of his escalation against the bombed out and besieged Palestinian enclave of Gaza, where his forces have already killed more than 52,000 Palestinians, many of them women and children.

In mid-April, current and former members of the air force, considered one of Israel’s elite units, also released a letter, claiming the war served the “political and personal interests” of Netanyahu, “and not security ones”.

Prompted by the air force, similar protests came from members of the navy, elite units within the military and Israel’s foreign security agency, Mossad.

Political and personal interests

Accusations that Netanyahu is manipulating the war for his own personal ends predate the breaking of the ceasefire.

In the minds of his critics, the longer the war continues, the longer Netanyahu feels he can defend himself against the numerous threats to his position and even his freedom.

In addition to facing trial on numerous counts of corruption dating back to 2019, he also faces calls to hold an inquiry into the government’s political failings before the October 7 attack.

Netanyahu also faces accusations that members of his office have allegedly been taking payment from Qatar – the Gulf state has previously dismissed the allegations as a “smear campaign” intended to hinder efforts to mediate an end to the conflict.

The continuation of the war allows Netanyahu to distract from those issues, while maintaining a coalition with far-right parties who have made it clear that any end to the war without total victory – which increasingly appears to include the ethnic cleansing of Gaza – would result in their departure from government, and Netanyahu’s likely fall.

And so there are questions about whether Netanyahu’s announcement of a further escalation in Gaza, including the occupation of territory and displacement of its population, will mark an end to the conflict, or simply bog Israel down in the kind of forever war that has so far been to Netanyahu’s benefit.

‘I don’t know if they’re capable of occupying the territory,” former US Special Forces commander, Colonel Seth Krummrich of international security firm Global Guardian told Al Jazeera, “Gaza is just going to soak up people, and that’s before you even think about guarding northern Israel, confronting Iran or guarding the Israeli street,” he said, warning of the potential shortfall in reservists.

“It’s also competing with a tide of growing [domestic] toxicity. When soldiers don’t return home, or don’t go, that’s going to tear at the fabric of Israeli society. It plays out at every dinner table.”

Staying at home

Israeli media reports suggest that part of that toxicity is playing out in the number of reservists simply not showing up for duty.

The majority of those refusing service are thought to be “grey refusers”. That is, reservists with no ideological objection to the mass killings in Gaza, but rather ones exhausted by repeated tours, away from their families and jobs to support a war with no clear end.

Official numbers of reservists refusing duty are unknown. However, in mid-March, the Israeli national broadcaster, Kan, ran a report disputing official numbers, which claimed that more than 80 percent of those called up for duty had attended, suggesting that the actual figure was closer to 60 percent.

“There has been a steady increase in refusal among reservists,” a spokesperson for the organisation New Profile, which supports people refusing enlistment, said. “However, we often see sharp spikes in response to specific shifts in Israeli government policy, such as the violation of the most recent ceasefire or public statements by officials indicating that the primary objective of the military campaign is no longer the return of hostages and ‘destruction of Hamas’, as initially claimed, but rather the occupation of Gaza, and its ethnic cleansing.”

Also unaddressed is growing public discontent over the ultra-religious Haredi community, whose eight-decade exemption from military service was deemed illegal by the Supreme Court in June of last year.

Despite the shortfall in reservists reporting for duty and others having experienced repeated deployments, in April, the Supreme Court requested an explanation from Netanyahu – who relies upon Haredi support to maintain his coalition – as to why its ruling had not been fully implemented or enforced.

Throughout the war, Netanyahu’s escalations, while often resisted by the captives’ families and their allies, have been cheered on and encouraged by his allies among the far-right, many of whom claim a biblical right to the homes and land of Palestinians.

The apparent conflict between the welfare of the captives and the “total victory” promised by Netanyahu has run almost as long as the conflict itself, with each moment of division seemingly strengthening the prime minister’s position through the critical support of the ultranationalist elements of his cabinet.

Netanyahu’s position has led to conflict with politicians, including his own former Defence Minister Yoav Gallant. While Gallant wasn’t opposed to the war in principle – his active support for Netanyahu eventually led to him joining Netanyahu in facing an arrest warrant from the International Criminal Court for war crimes – his prioritisation of the captives put him at odds with the prime minister.

The divide over priorities has meant that civility between the government and the captives’ families has increasingly gone out the window, with Netanyahu generally avoiding meeting families with loved ones still captive in Gaza, and far-right politicians engaging in shouting matches with them during meetings in parliament.

Division within Israeli society was not new, Professor Yossi Mekelberg of Chatham House told Al Jazeera, “but wars and conflicts deepen them”.

“Now we have a situation where some people have served anywhere up to 400 days in the army [as reservists], while others are refusing to serve at all and exploiting their political power within the coalition to do so,” Mekelberg added.

“Elsewhere, there are ministers on the extreme right talking about ‘sacrificing’ the hostages for military gain,” something Mekelberg said many regarded as running counter to much of the founding principles of the country and the Jewish faith.

“There’s such toxicity in public discourse,” Mekelberg continued, “We see toxicity against anyone who criticises the war or the prime minister, division between the secular and the religious, and then even divisions within the religious movements.”

-

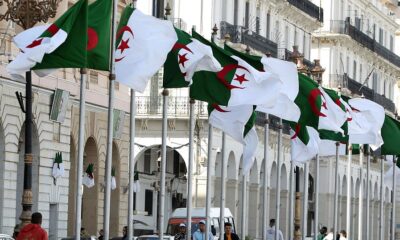

Africa2 days ago

Africa2 days agoAlgeria commemorates thousands killed by French troops in 1945 massacres

-

Europe2 days ago

Europe2 days agoThe Bank of England cuts interest rates as tariffs endanger global economic growth

-

Middle East2 days ago

Middle East2 days agoKey takeaways: Documentary names alleged killer of Al Jazeera’s Abu Akleh | Crime News

-

Middle East2 days ago

Middle East2 days agoDocumentary sheds light on Biden’s reactions to Shireen Abu Akleh’s killing | Occupied West Bank News

-

Conflict Zones2 days ago

Conflict Zones2 days agoInside Muridke: Did India hit a ‘terror base’ or a mosque? | India-Pakistan Tensions

-

Middle East2 days ago

Middle East2 days agoIsrael retrofitting DJI commercial drones to bomb and surveil Gaza | Israel-Palestine conflict News

-

Conflict Zones1 day ago

Conflict Zones1 day ago‘Missiles in skies’: Panic in Indian frontier cities as war clouds gather | India-Pakistan Tensions News

-

Africa1 day ago

Africa1 day agoHeavy shelling over Kashmir Line of Control leaves at least 5 civilians dead