Lifestyle

Accents are fading in parts of the US South, linguists say

Growing up in Atlanta in the 1940s and 1950s, Susan Levine’s visits to New York City relatives included being the star of an impromptu novelty show: Her cousin invited over friends and charged 25 cents a pop for them to listen to Levine’s Southern accent.

Even though they too grew up in Atlanta, Levine’s two sons, born more than a quarter century after her, never spoke with the accent that is perhaps the most famous regional dialect in the United States, with its elongated vowels and soft “r” sounds.

“My accent is nonexistent,” said Ira Levine, her oldest son. “People I work with, and even in school, people didn’t believe I was from Atlanta.”

The Southern accent, which has many variations, is fading in some areas of the South as people migrate to the region from other parts of the U.S. and around the world. A series of research papers published in December documented the diminishment of the regional accent among Black residents of the Atlanta area, white working-class people in the New Orleans area and people who grew up in Raleigh, North Carolina.

More than 5.8 million people have moved into the U.S. South so far in the 2020s, more than four times the combined total of the nation’s three other regions. Linguists don’t believe mass media has played a significant role in the language change, which tends to start in urban areas and radiate out to more rural places.

Late 20th century migration surge affects accents

The classical white Southern accent in the Atlanta area and other parts of the urban South peaked with baby boomers born between 1946 and 1964 and then dropped off with Gen Xers born between 1965 and 1980 and subsequent generations, in large part because of the tremendous in-migration of people in the second half of the 20th century.

It has been replaced among the youngest speakers in the 21st century with a dialect that was first noticed in California in the late 1980s, according to recent research from linguists at the University of Georgia, Georgia Tech and Brigham Young University. That dialect, which also was detected in Canada, has become a pan-regional accent as it has spread to other parts of the U.S., including Boston, New York and Michigan, contributing to the diminishment of their regional accents.

In Raleigh, North Carolina, the trigger point in the decline of the Southern accent was the opening in 1959 of the Research Triangle Park, a sprawling complex of research and technology firms that attracted tens of thousands of highly educated workers from outside the South. White residents born after 1979, a generation after the Research Triangle’s establishment, typically don’t talk with a Southern accent, linguist Sean Lundergan wrote in a paper published in December.

Often, outsiders wrongly associate a Southern accent with a lack of education, and some younger people may be trying to distance themselves from that stereotype.

“Young people today, especially the educated young people, they don’t want to sound too much like they are from a specific hometown,” said Georgia Tech linguist Lelia Glass, who co-wrote the Atlanta study. “They want to sound more kind of, nonlocal and geographically mobile.”

Accents change for younger people

The Southern dialect among Black people in Atlanta has dropped off in recent decades mainly because of an influx of African Americans from northern U.S. cities in what has been described as the “Reverse Great Migration.”

During the Great Migration, from roughly 1910 to 1970, African Americans from the South moved to cities in the North like New York, Detroit and Chicago. Their grandchildren and great-grandchildren have moved back South in large numbers to places like Atlanta during the late 20th and early 21st centuries and are more likely to be college-educated.

Researchers found Southern accents among African Americans dropped off with Gen Z, or those born between 1997 and 2012, according to a study published in December. The same researchers previously studied Southern accents among white people in Atlanta.

Michelle and Richard Beck, Gen Xers living in the Atlanta area, have Southern accents, but it’s missing in their two sons born in 1998 and 2001.

“I think they speak clearer than I do,” Richard Beck, a law enforcement officer, said of his sons. “They don’t sound as country as I do when it comes to the Southern drawl.”

New Orleans ‘yat’ accent diminished

Unlike other accents that have changed because of an influx of new residents, the distinctive, white working-class “yat” accent of New Orleans has declined as many locals left following the devastating Hurricane Katrina in 2005. The accent is distinct from other regional accents in the South and often described as sounding as much like Brooklynese as Southern.

The hurricane was a “catastrophic” language change event for New Orleans since it displaced around a quarter million residents in the first year after the storm and brought in tens of thousands of outsiders in the following decade.

The diminishment of the “yat” accent is most noticeable in millennials, who were adolescents when Katrina hit, since they were exposed to other ways of speaking during a key time for linguistic development, Virginia Tech sociolinguist Katie Carmichael said in a paper published in December.

Cheryl Wilson Lanier, a 64-year-old who grew up in Chalmette, Louisiana, one of the New Orleans suburbs where the accent was most prevalent, worries that part of the region’s uniqueness will be lost if the accent disappears.

“It’s kind of like we’re losing our distinct personality,” she said.

Southern identity changing

While it is diminishing in many urban areas, the Southern accent is unlikely to disappear completely because “accents are an incredibly straightforward way of showing other people something about ourselves,” said University of Georgia linguist Margaret Renwick, one of the authors of the Atlanta studies.

It may instead reflect a change in how younger speakers view Southern identity, with a regional accent not as closely associated with what is considered Southern as in previous generations, and linguistic boundaries less important than other factors, she said.

“So young people in the Atlanta area or Raleigh area have a different vision of what life is in the South,” Renwick said. “And it’s not the same as the one that their parents or grandparents grew up with.”

___

Follow Mike Schneider on the social platform Bluesky: @mikeysid.bsky.social.

Lifestyle

In coffee-producing Uganda, an emerging sisterhood wants more women involved

SIRONKO, Uganda (AP) — Meridah Nandudu envisioned a coffee sisterhood in Uganda, and the strategy for expanding it was simple: Pay a higher price per kilogram when a female grower took the beans to a collection point.

It worked. More and more men who typically made the deliveries allowed their wives to go instead.

Nandudu’s business group now includes more than 600 women, up from dozens in 2022. That’s about 75% of her Bayaaya Specialty Coffee’s pool of registered farmers in this mountainous area of eastern Uganda that produces prized arabica beans and sells to exporters.

“Women have been so discouraged by coffee in a way that, when you look at (the) coffee value chain, women do the donkey work,” Nandudu said. But when the coffee is ready for selling, men step in to claim the proceeds.

Her goal is to reverse that trend in a community where coffee production is not possible without women’s labor.

Uganda is one of Africa’s top two coffee producers, and the crop is its leading export. The east African country exported more than 6 million bags of coffee between September 2023 and August 2024, accounting for $1.3 billion in earnings, according to the Uganda Coffee Development Authority.

The earnings have been rising as production dwindles in Brazil, the world’s top coffee producer, which faces unfavorable drought conditions.

In Sironko district, where Nandudu grew up in a remote village near the Kenya border, coffee is the community’s lifeblood. As a girl, when she was not at school, she helped her mother and other women look after acres of coffee plants. They usually planted, weeded and toiled with the post-harvest routine that includes pulping, fermenting, washing and drying the coffee.

The harvest season was known to coincide with a surge in cases of domestic violence, she said. Couples fought over how much of the earnings that men brought home from sales — and how much they didn’t.

“When (men) go and sell, they are not accountable. Our mothers cannot ask, ‘We don’t have food at home. You sold coffee. Can you pay school fees for this child?’” she said.

Years later, Nandudu earned her degree in the social sciences from Uganda’s top public university in 2015, with her father funding her education from coffee earnings. She had the idea to launch a company that would prioritize the needs of coffee-producing women in the country’s conservative society.

She thought of her project as a kind of sisterhood and chose “bayaaya” — a translation in the Lumasaba language — for her company’s name.

It launched in 2018, operating like others that buy coffee directly from farmers and process it for export.

But Bayaaya is unique in Mbale, the largest city in eastern Uganda, for focusing on women and for initiatives such as a cooperative saving society that members can contribute to and borrow from.

For small-holder Ugandan farmers in remote areas, a small movement in the price of a kilogram of coffee is a major event. The decision to sell to one or another middleman often hinges on small price differences.

A decade ago, the price of coffee bought by a middleman from a Ugandan farmer was roughly 8,000 Uganda shillings, or just over $2 at today’s exchange rate. Now the price is roughly $5.

Nandudu adds an extra 200 shillings to the price of every kilogram she buys from a woman. It’s enough of an incentive that more women are joining. Another benefit is a small bonus payment during the off-season from February to August.

That motivates many local men “to trust their women to sell coffee,” Nandudu said. “When a woman sells coffee, she has a hand in it.”

Nandudu’s group has many collection points across eastern Uganda, and women trek to them at least twice a week. Men are not turned away.

Selling as a Bayaaya member has fostered teamwork as her family collectively decides how to spend coffee earnings, said Linet Gimono, who joined the group in 2022.

And with assured earnings, she’s able to afford the “small things” she often needs as a woman. “I can buy soap (and) I can buy sugar without pulling ropes with my husband over it,” she said.

Another member, Juliet Kwaga, said her mother never would have thought of collecting coffee earnings because her father was very much in charge.

Now, Kwaga’s husband, with a bit of encouragement, is comfortable sending her. “At the end of the day I go home with something to feed my family, to support my children,” she said.

In Sironko district, home to more than 200,000 people, coffee trees dot the hilly terrain. Much of the farming is on plots of one or two acres, although some families have larger tracts.

Many farmers don’t usually drink coffee, and some have never tasted it. Some women smiled in embarrassment when asked what it tasted like.

But things are slowly changing. Routine coffee drinkers are emerging among younger women in the coffee business in urban areas, including at a roasting place in Mbale where most employees are women.

Phoebe Nabutale, who helps oversee quality assurance for Darling Coffee, was raised in a family of coffee growers. She bent over the roaster, smelling the beans until she got the aroma she wanted.

Many of her girlfriends, she said, regularly ask how they can break into the coffee business, as roasters or otherwise.

For Nandudu, who aims to start exporting beans, that’s progress.

Now there are more women in “coffee as a business,” she said.

___

For more on Africa and development: https://apnews.com/hub/africa-pulse

The Associated Press receives financial support for global health and development coverage in Africa from the Gates Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Lifestyle

Two dolls instead of 30? Toys become the latest symbol of Trump’s trade war

NEW YORK (AP) — President Donald Trump’s tariffs crusade has taken aim at a number of foreign goods, from European wines and car parts from Mexico to films made abroad. Lately, the president’s wandering ire has found another rhetorical poster child: toy dolls.

Trump asserted that children will be fine having two dolls — perhaps three or five — instead of 30 if U.S. import taxes increase consumer prices. The response on social media included memes of him portrayed as the Grinch and photos of a young Barron Trump’s child-sized Mercedes convertible.

“COMPLETELY out of touch,” The Loyal Subjects CEO Jonathan Cathey, whose collectible toy company in Los Angeles produces Strawberry Shortcake and Rainbow Brite dolls, wrote on Linkedin. “If that ain’t a ‘Let them eat cake’ moment shot through the echoes of history? Love how toys and dolls have become THE martyr metaphor for this nonsensical trade war incoherence.”

The president’s comments also touched a nerve with parents, both ones who took offense at the casual way he hypothesized that perhaps “two dolls will cost a couple bucks more” and those who acknowledged their own kids have more toys than they need.

Either way, the U.S. toy industry has a lot riding on a possible deescalation of the tariff standoff between the Trump administration and the government in Beijing. Nearly 80% of the toys sold in the U.S. come from China.

The Toy Association, a trade group, has lobbied for an immediate reprieve from the 145% tariff rate the president put on Chinese-made products. Some toy companies warn the likelihood of holiday shortages increases each week the tariff remains in effect.

Here’s a snapshot of the doll debate and how tariffs are impacting toys:

How much is the US doll market worth?

From Barbie, Bratz and Cabbage Patch Kids to Adora baby dolls, American Girl and Our Generation, dolls are a big business in the U.S. as well as beloved playthings.

The doll category, which includes accessories like clothes, generated U.S. sales of $2.7 billion last year compared to $2.9 billion in 2023 and $3.4 billion in 2019, according to market research firm Circana.

Consumers splurged on toys during the height of the COVID pandemic to keep children and themselves occupied, but sales flattened as inflation seized the economy.

Younger girls becoming more interested in buying makeup and skincare also has cooled the demand for dolls, Marshal Cohen, Circana’s chief retail advisor, said.

What are toy companies doing to navigate tariffs?

The nation’s largest toy maker, Mattel, said this week it would have to raise prices for some products sold in the U.S. to offset higher costs related to tariffs.

The company, whose brands include Barbie and American Girl, said the increases were necessary even though it’s speeding up the expansion of its manufacturing base outside of China.

Smaller toy companies are expected to have a harder time than Mattel and Hasbro, which makes the eating, drinking and diaper-wetting Baby Alive. Cathey said he paused The Loyal Subjects’ shipments from China in April because he couldn’t pay the stratospheric tariff they would have incurred.

“Nobody insulates themselves with that much cash,” he said.

With about four months’ worth of inventory on hand, Cathey said his ability to secure holiday stock depends on a break in the U.S.-China trade standoff happening in the next two weeks since it would take time for cargo operations to resume.

Cepia, a Missouri company that was behind the 2009 holiday season hit Zhu Zhu Pets, launched a line of 11-inch fashion dolls called Decora Girlz last year. CEO James Russell Hornsby said he was working to relocate some production but the move won’t happen in time to replace the orders he planned to get from China.

Hornsby described himself as a Trump supporter and said he understands the administration’s desire to reduce trade imbalances.

“Let’s just get the deals done and stop all this because (Trump’s) disrupting Christmas,” he said.

What goes into making a doll?

Although American Girl launched in 1986 with a line based on fictional historical characters, the dolls never were domestic products. They were made in Germany before production eventually moved to China.

Toy experts say that in addition to lower costs, Chinese factories have developed techniques and expertise that are not easily replicated.

“We don’t have any capacity in the U.S. to make rooted doll hair. And then you’ve got things like the faces. Some of them are hand-painted, others are done with a Tampo (printing) machine,” James Zahn, editor-in-chief of industry publication The Toy Book, said of doll-making.

Hornsby said rooting the synthetic hair onto the heads of Decora Girlz dolls is carried out by skilled workers at factories in Guangzhou and Dongguan, China.

“It’s not just sticking into a machine and it automatically does it,” he said. ”You have to know what you’re doing in order to make that doll look like it’s got a full set of hair when literally maybe only 60% of the head is filled with hair.”

Are toys from China safe?

White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller said last week that he assumes consumers would prefer to pay more for American-made products. Dolls made in China might have lead paint in them, he said.

Teresa Murray, consumer watchdog director at the U.S. Public Interest Research Group, said the picture is more complicated.

Products for children ages 12 and under require third-party testing and certification from labs approved by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, the agency tasked with enforcing lead levels in toys, Murray said.

The rules apply to all products sold in the U.S. Toys by major brands such as Fisher-Price, Mattel, Hasbro and Lego, which have long outsourced manufacturing to China, are usually in compliance, she said.

But the rise of online shopping, including e-commerce platforms that ship directly to U.S. consumers from overseas, has posed a challenge, according to Murray. When valued at less than $800, such parcels entered the U.S. duty-free and were not subject to the same scrutiny as bulk imports, she said.

The White House eliminated the customs exemption starting May 2 for low-value parcels that originated in mainland China and Hong Kong. U.S Customs and Border Protection expects additional oversight will make it easier to flag problems.

Toy companies and industry experts argue the high tariffs on Chinese imports will tempt price-sensitive shoppers to search for cheap counterfeit toys that carry higher safety risks.

Can children have too many dolls?

Plenty of people agree American consumer culture has gotten out of hand, in large part due to prices kept low through the labor of foreign factory workers who earn much less than they would in the U.S.

Katie Walley-Wiegert, 38, a senior marketer in Richmond, Virginia, and the parent of a 2-year-old son, agrees there’s too much materialism but thinks parents should have choices when deciding what is best for their children. She found the wealthy Trump’s comments off-putting.

“I think it is a small view of what purchase habits and realities are for people who buy toys for kids,” Walley-Wiegert said.

San Francisco resident Elenor Mak, who founded the Jilly Bing doll company after she couldn’t find an Asian American doll for her daughter, Jillian, now 5, said the president’s remarks upset her because some families struggle to buy even one doll.

The trade war with China “just makes it even more impossible for those families,” Mak said.

Lifestyle

Indigenous fashion week in Santa Fe, New Mexico, explores heritage in silk and hides

SANTA FE, N.M. (AP) — Fashion designers from across North America are bringing inspiration from their Indigenous heritage, culture and everyday lives to three days of runway modeling starting Friday in a leading creative hub and marketplace for Indigenous art.

A fashion show affiliated with the century-old Santa Fe Indian Market is collaborating this year with a counterpart from Vancouver, Canada, in a spirit of Indigenous solidarity and artistic freedom. A second, independent runway show at a rail yard district in the city has nearly doubled the bustle of models, makeup and final fittings.

Three days of runway shows set to music will have models that include professionals and family, dancers and Indigenous celebrities from TV and the political sphere.

Clothing and accessories rely on materials ranging from of silk to animal hides, featuring traditional beadwork, ribbons and jewelry with some contemporary twists that include digitally rendered designs and urban Native American streetwear from Phoenix.

“Native fashion, it’s telling a story about our understanding of who we are individually and then within our communities,” said Taos Pueblo fashion designer Patricia Michaels, of “Project Runway” reality TV fame. “You’re getting designers from North America that are here to express a lot of what inspires them from their own heritage and culture.”

Santa Fe style

The stand-alone spring fashion week for Indigenous design is a recent outgrowth of haute couture at the summer Santa Fe Indian Market, where teeming crowds flock to outdoor displays by individual sculptors, potters, jewelers and painters.

Designer Sage Mountainflower remembers playing in the streets at Indian Market as a child in the 1980s while her artist parents sold paintings and beadwork. She forged a different career in environmental administration, but the world of high fashion called to her as she sewed tribal regalia for her children at home and, eventually, brought international recognition.

At age 50, Mountainflower on Friday is presenting her “Taandi” collection — the Tewa word for “Spring” — grounded in satin and chiffon fabric that includes embroidery patterns that invoke her personal and family heritage at the Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo in the Upper Rio Grande Valley.

“I pay attention to trends, but a lot of it’s just what I like,” said Mountainflower, who also traces her heritage to Taos Pueblo and the Navajo Nation. “This year it’s actually just looking at springtime and how it’s evolving. … It’s going to be a colorful collection.”

More than 20 designers are presenting at the invitation of the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts.

Fashion plays a prominent part in Santa Fe’s renowned arts ecosystem, with Native American vendors each day selling jewelry in the central plaza, while the Institute for American Indian Arts delivers fashion-related college degrees in May.

This week, a gala at the New Mexico governor’s mansion welcomed fashion designers to town, along with social mixers at local galleries and bookstores and plans for pop-up fashion stores to sell clothes fresh off the fashion runway.

International vision

A full-scale collaboration with Vancouver Indigenous Fashion Week is bringing a northern, First Nations flair to the gathering this year with many designers crossing into the U.S. from Canada.

Secwépemc artist and fashion designer Randi Nelson traveled to Santa Fe from the city of Whitehorse in the Canadian Yukon to present collections forged from fur and traditionally cured hides — she uses primarily elk and caribou. The leather is tanned by hand without chemicals using inherited techniques and tools.

“We’re all so different,” said Nelson, a member of the Bonaparte/St’uxwtéws First Nation who started her career in jewelry assembled from quills, shells and beads. “There’s not one pan-Indigenous theme or pan-Indigenous look. We’re all taking from our individual nations, our individual teachings, the things from our family, but then also recreating them in a new and modern way.”

Urban Indian couture

Phoenix-based jeweler and designer Jeremy Donavan Arviso said the runway shows in Santa Fe are attempting to break out of the strictly Southwest fashion mold and become a global venue for Native design and collaboration. A panel discussion Thursday dwelled on the threat of new tariffs and prices for fashion supplies — and tensions between disposable fast fashion and Indigenous ideals.

Arviso is bringing a street-smart aesthetic to two shows at the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts runway and a warehouse venue organized by Amber-Dawn Bear Robe, from the Siksika Nation.

“My work is definitely contemporary, I don’t choose a whole lot of ceremonial or ancestral practices in my work,” said Arviso, who is Diné, Hopi, Akimel O’odham and Tohono O’odham, and grew up in Phoenix. “I didn’t grow up like that. … I grew up on the streets.”

Arviso said his approach to fashion resembles music sampling by early rap musicians as he draws on themes from major fashion brands and elements of his own tribal cultures. He invited Toronto-based ballet dancer Madison Noon for a “beautiful and biting” performance to introduce his collection titled Vision Quest.

Santa Fe runway models will include former U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland of Laguna Pueblo, adorned with clothing from Michaels and jewelry by Zuni Pueblo silversmith Veronica Poblano.

-

Lifestyle2 days ago

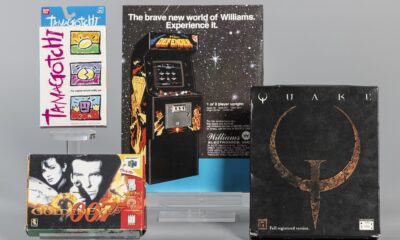

Lifestyle2 days agoWorld Video Game Hall of Fame inducts Defender, Tamagotchi, GoldenEye 007 and Quake

-

Europe2 days ago

Europe2 days agoThe Bank of England cuts interest rates as tariffs endanger global economic growth

-

Middle East2 days ago

Middle East2 days agoDocumentary sheds light on Biden’s reactions to Shireen Abu Akleh’s killing | Occupied West Bank News

-

Europe1 day ago

Europe1 day ago‘Father of haute couture’: The man who pioneered fashion as we know it

-

Conflict Zones18 hours ago

Conflict Zones18 hours agoWho are the armed groups India accuses Pakistan of backing? | Armed Groups News

-

Africa20 hours ago

Africa20 hours agoRussia stages massive victory day parade, Putin hails troops in Ukraine as foreign leaders attend

-

Europe21 hours ago

Europe21 hours agoUkraine’s Western allies pile pressure on Putin, threatening sanctions if he refuses 30-day truce

-

Lifestyle21 hours ago

Lifestyle21 hours agoTwo dolls instead of 30? Toys become the latest symbol of Trump’s trade war