Conflict Zones

Hezbollah leader says Lebanese gov’t must do more to end Israeli attacks | Hezbollah News

Naim Qassem’s comments came as the Israeli military said it carried out more than 50 strikes in Lebanon this month.

Hezbollah leader Naim Qassem has called on Lebanon’s government to work harder to end Israel’s daily attacks in the country, a day after an Israeli air strike targeted the southern suburbs of the capital Beirut for the third time since a ceasefire was agreed late last November.

Qassem said in a televised speech on Monday that Hezbollah implemented the ceasefire deal that ended the 14-month war, but Israel has continued to launch relentless air strikes.

Qassem’s comments came as the Israeli military said it carried out more than 50 strikes in Lebanon this month in response, it says, to threats against Israel and Hezbollah allegedly violating the United States-brokered ceasefire.

Rights groups have denounced Israeli attacks on Lebanon, saying they are violating the truce deal.

On Sunday, Israeli warplanes struck Beirut’s southern suburbs after issuing a warning about an hour earlier, marking the third Israeli strike on the area since the November ceasefire. The Israeli military said it struck a precision-guided missiles facility.

‘Put pressure on America’

Following the strike, Lebanese President Joseph Aoun accused Israel of undermining stability in Lebanon and escalating tensions. He said Israeli attacks pose “real dangers to the security” of the region.

“Yesterday, an aggression targeted the southern suburbs of Beirut. This attack lacks any justification … It is a political attack aimed at changing the rules by force,” Qassem said of Sunday’s attack.

“The resistance complied 100 percent with the [ceasefire] deal and I tell state officials that it’s your duty to guarantee protection,” Qassem said, adding that Lebanese officials should contact sponsors of the ceasefire so that they put pressure on Israel to cease its attacks.

“Put pressure on America and make it understand that Lebanon cannot rise if the aggression doesn’t stop,” Qassem said, pointing to Lebanese officials. He added that the US has interests in Lebanon and “stability achieves these interests”.

Qassem said the priority should be for a full Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon, an end to Israeli strikes in the country, and the release of Lebanese people held in Israel since the war officially ended on November 27.

Hezbollah began launching rockets, drones and missiles into Israel the day after its ally Hamas led the October 7, 2023 attack and Israel responded with mass bombardment of Gaza. About 1,200 people in Israel were killed and another 251 others were abducted during the attack in southern Israel.

The war ignited further last September when Israel carried out waves of air strikes across Lebanon and assassinated most of the group’s senior leaders, including Hassan Nasrallah. The fighting killed more than 4,000 people in Lebanon, most of them civilians.

The Lebanese government said earlier this month that 190 people have been killed and 485 injured in Lebanon by Israeli strikes since the ceasefire took effect.

Conflict Zones

Pahalgam attack: A simple guide to the Kashmir conflict | Border Disputes News

Islamabad, Pakistan – Pakistan and India continue to engage in war rhetoric and have exchanged fire across the Line of Control (LoC), the de facto border in Kashmir, days after the Pahalgam attack, in which 26 civilians were killed in Indian-administered Kashmir on April 22.

Since then, senior members of Pakistan’s government and military officials have held multiple news conferences in which they have claimed to have “credible information” that an Indian military response is imminent.

This is not the first time South Asia’s two largest countries – which have a combined population of more than 1.6 billion people, about one-fifth of the world’s population – have found themselves under the shadow of potential war.

At the heart of their longstanding animosity lies the status of the picturesque valley of Kashmir, over which India and Pakistan have fought three of their four previous wars. Since gaining independence from British rule in 1947, both countries have controlled parts of Kashmir – with China controlling another part of it – but continue to claim it in full.

So what is the Kashmir conflict all about, and why do India and Pakistan continue to fight over it nearly eight decades after independence?

What are the latest tensions about?

India has implied it believes Pakistan may have indirectly supported the Pahalgam attack – a claim Pakistan strongly denies. Both countries have engaged in tit-for-tat diplomatic swipes at each other, including cancelling visas for each other’s citizens and recalling diplomatic staff.

India has suspended its participation in the Indus Waters Treaty, a water use and distribution agreement with Pakistan. Pakistan has in turn threatened to walk away from the Simla Agreement, which was signed in July 1972, seven months after Pakistan decisively lost the 1971 war that led to the creation of Bangladesh. The Simla Agreement has since formed the bedrock of India-Pakistan relations. It governs the LoC and outlines a commitment to resolve disputes through peaceful means.

On Wednesday, United States Secretary of State Marco Rubio called Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif and Indian External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar to urge both countries to work together to “de-escalate tensions and maintain peace and security in South Asia”.

US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth also called Indian Defence Minister Rajnath Singh on Thursday to condemn the attack. “I offered my strong support. We stand with India and its great people,” Hegseth wrote on X.

What lies at the heart of the Kashmir conflict?

Situated in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent, the region spans 222,200 square kilometres (85,800sq miles) with about four million people living in Pakistan-administered Kashmir and 13 million in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir.

The population is overwhelmingly Muslim. Pakistan controls the northern and western portions, namely Azad Kashmir, Gilgit and Baltistan, while India controls the southern and southeastern parts, including the Kashmir Valley and its biggest city, Srinagar, as well as Jammu and Ladakh.

The end of British colonial rule and the partition of British India in August 1947 led to the creation of Muslim-majority Pakistan and Hindu-majority India.

At the time, princely states like Jammu and Kashmir were given the option to accede to either country. With a nearly 75 percent Muslim population, many in Pakistan believed the region would naturally join that country. After all, Pakistan under Muhammad Ali Jinnah was created as a homeland for Muslims, even though a majority of Muslims in what remained as India after partition stayed back in that country, where Mahatma Gandhi and independent India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, built the foundations of a secular state.

The maharaja of Kashmir initially sought independence from both countries but later chose to join India after Pakistan invaded, triggering the first war from 1947 to 1948. The ceasefire line established after that was formalised as the LoC in the Simla Agreement.

Despite this, both countries continue to assert claims to the entire region, including, in the case of India, to China-administered Aksai Chin on the eastern side.

What triggered the first Indo-Pakistan war in 1947?

The ruling Hindu maharaja of Kashmir was Hari Singh, whose forefathers took control of the region as part of an agreement with the British in 1846.

At the time of partition, Singh initially sought to retain Kashmir’s independence from both India and Pakistan.

But by then, a rebellion against his rule by pro-Pakistani residents in a part of Kashmir had broken out. Armed groups from Pakistan, backed by the government of the newly formed country, invaded and tried to take over the region.

Sheikh Abdullah, the most prominent Kashmiri leader at the time, opposed the Pakistani-backed attack. Hari Singh appealed to India for military assistance.

Nehru’s government intervened against Pakistan – but on the condition that the maharaja sign an Instrument of Accession merging Jammu and Kashmir with India. In October 1947, Jammu and Kashmir officially became part of India, giving New Delhi control over the Kashmir Valley, Jammu and Ladakh.

India accused Pakistan of being the aggressor in the conflict – a charge Pakistan denied – and took the matter to the United Nations in January 1948. A key resolution was passed stating: “The question of the accession of Jammu and Kashmir to India or Pakistan should be decided through the democratic method of a free and impartial plebiscite.” Nearly 80 years later, no plebiscite has been held – a source of grievance for Kashmiris.

The first war over Kashmir finally ended with a UN-mediated ceasefire, and in 1949, the two countries formalised a ceasefire line under an agreement signed in Karachi, Pakistan’s then-capital. The new line divided Kashmir between Indian- and Pakistani-controlled parts.

How did the situation change after the 1949 agreement?

By 1953, Sheikh Abdullah had founded the Jammu Kashmir National Conference (JKNC) and won state elections in Indian-administered Kashmir.

However, his increasing interest in seeking independence from India led to his arrest by Indian authorities. In 1956, Jammu and Kashmir was declared an “integral” part of India.

In September 1965, less than two decades after independence, India and Pakistan went to war over the region again.

Pakistan hoped to aid the Kashmiri cause and incite a local uprising, but the war ended in a stalemate, with both sides agreeing to a UN-supervised ceasefire.

How did China get a part of Kashmir?

The Aksai Chin region in the northeast of the region sits at an elevation of 5,000 metres (16,400 feet), and through history, was a hard-to-reach, barely inhabited territory that in the 19th and early 20th centuries sat at the border of British India and China.

It was a part of the kingdom that Kashmir’s Hari Singh inherited as a result of the 1846 deal with the British. Until the 1930s, at least, Chinese maps too recognised Kashmir as being south of the Ardagh-Johnson Line that marked the northeastern boundary of Kashmir.

After 1947 and Singh’s accession to India, New Delhi viewed Aksai Chin as part of its territory. But by the early 1950s, China – now under communist rule – built a massive 1,200km (745-mile) long highway connecting Tibet and Xinjiang, and running through Aksai Chin.

India was caught unaware – the desolate region had not been a security priority until then. In 1954, Nehru called for the border to be formalised according to the Ardagh-Johnson Line – in effect, recognising Aksai Chin as a part of India.

But China insisted that the British had never discussed the Ardagh-Johnson Line, and that Aksai Chin belonged to it under an alternate map. Most importantly, though, China already had boots on the ground in Aksai Chin because of the highway.

Meanwhile, Pakistan and China also had differences over who controlled what in parts of Kashmir. But by the early 1960s, they reached an agreement: China gave up grazing grounds that Pakistan had sought, and in return, Pakistan ceded a thin slice of northern Kashmir to China.

India claims this deal was illegal since, according to the Instrument of Accession of 1947, all of Kashmir belonged to it.

Back to India and Pakistan: What happened next?

Another war followed in December 1971 – this time over what was then known as East Pakistan, following a popular revolt by India-backed Bengali nationalists against Pakistan’s rule. The war led to the creation of Bangladesh. More than 90,000 Pakistani soldiers were captured by India as prisoners of war.

The Simla Agreement converted the ceasefire line into the LoC, a de facto but not internationally recognised border, yet again leaving Kashmir’s status in question.

But after India’s decisive 1971 victory and amid the growing political influence of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi – Nehru’s daughter – the 1970s saw Abdullah abandon his demand for a plebiscite and the Kashmiri people’s right of self-determination.

In 1975, he signed an accord with Gandhi, recognising India-administered Kashmir’s accession to India while retaining semi-autonomous status under Article 370 of the Indian Constitution. He later served as the region’s chief minister.

What led to a renewed drive for Kashmiri independence in the 1980s?

As ties grew between Abdullah’s National Conference Party and India’s ruling Indian National Congress, so did frustration among Kashmiris in India-controlled Kashmir, who felt that socioeconomic conditions had not improved in the region.

Separatist groups like the Jammu-Kashmir Liberation Front, founded by Maqbool Bhat, rose.

India’s claims of democracy in Kashmir faltered in the face of growing support for the armed groups. A tipping point was the 1987 election to the state legislature, which saw Abdullah’s son, Farooq Abdullah, come to power, but which was widely viewed as heavily rigged to keep out popular, anti-India politicians.

Indian authorities launched a severe crackdown on separatist groups, which New Delhi alleged were supported and trained by Pakistan’s military intelligence. Pakistan, for its part, has consistently maintained it provides only moral and diplomatic support, backing the Kashmiris’ “right to self-determination”.

In 1999, conflict erupted in Kargil, where Indian and Pakistani forces fought for control over strategic heights along the LoC. India eventually regained the lost territory, and the pre-conflict status quo was restored. This was the third war over Kashmir – Kargil is a part of Ladakh.

How have tensions over Kashmir escalated since then?

The following years saw a gradual reduction in direct conflict, with multiple ceasefires signed. However, India significantly ramped up its military presence in the valley.

Tensions were reignited in 2016 after the killing of Burhan Wani, a popular separatist figure. His death led to a rise in violence in the valley and more frequent exchanges of fire along the LoC.

Major attacks in Indian-administered Kashmir, including those in Pathankot and Uri in 2016, targeted Indian forces, who blamed Pakistan-backed armed groups.

The most serious escalation came in February 2019 when a convoy of Indian paramilitary personnel was attacked in Pulwama, killing 40 soldiers and bringing the two nations to the brink of war.

Six months later, the Indian government under Prime Minister Narendra Modi unilaterally abrogated Article 370, stripping Jammu and Kashmir of its semi-autonomous status. Pakistan condemned the move as a violation of the Simla Agreement.

The decision led to widespread protests in the valley. India deployed 500,000 to 800,000 soldiers, placed the region under lockdown, shut down internet services and detained thousands of people.

India insists that Pakistan is to blame for the ongoing crisis in Kashmir. It accuses Pakistan of hosting, financing and training the Pakistan-based armed groups that have claimed responsibility for multiple attacks in Indian-administered Kashmir over the decades. Some of these groups are also accused by India, the US, and others of attacking other parts of India – such as during the 2008 attack on Mumbai, India’s financial capital, when at least 166 people were killed over three days.

Pakistan continues to deny that it fuels violence in India-controlled Kashmir and instead points to widespread resentment among locals, accusing India of imposing harsh and undemocratic rule in the region. Islamabad says it only supports Kashmiri separatism diplomatically and morally.

Conflict Zones

The $10bn India-Pakistan trade secret hidden by official data | Trade War News

In the days after gunmen killed at least 26 people in the picturesque tourist resort of Pahalgam in India-administered Kashmir last week, India and Pakistan announced a string of diplomatic moves against each other, including shutting down cross-border trade and suspending visas.

New Delhi accused Islamabad of involvement in the April 22 attack, suspended India’s participation in an Indus River water-sharing agreement that ensures Pakistan’s water supply and trimmed down diplomatic missions.

Islamabad has denied India’s accusations, called for a neutral investigation into the attack and announced it would suspend all trade with India, including through third countries, among other retaliatory measures. India-Pakistan trade relations have been frozen since 2019.

Both countries have also closed the Wagah-Attari crossing, the main land border between India and Pakistan.

But while official figures show minimal trade between the neighbouring countries, experts said billions of dollars of hidden, backdoor trading does continue.

So what is the real scale of trade between these archrivals? And will the suspension of trade and closure of the land border truly impact trading still taking place between the two countries?

Have India and Pakistan traded freely in the past?

Yes. Trade between India and Pakistan began after the two countries were created out of British India in 1947 through partition.

Trading volumes grew when New Delhi bestowed Islamabad with the “most favoured nation” (MFN) status in 1996 – a World Trade Organization rule that ensures a country treats all its trading partners equally with respect to tariffs and trade concessions.

But amid broader bilateral tensions between the nuclear armed neighbours, trade never fully took off. At least officially.

In the financial year 2017-2018, total trade between India and Pakistan stood at $2.41bn, compared with $2.27bn in 2016-2017. India exported goods worth $1.92bn to Pakistan and imported goods valued at $488.5m.

But in 2019, India revoked Pakistan’s MFN status after a suicide bombing in Pulwama in India-administered Kashmir killed at least 40 Indian paramilitary personnel.

From 2018 to 2024, bilateral trade fell from $2.41bn to $1.2bn. Pakistani exports to India plummeted from $547.5m in 2019 to just $480,000 in 2024.

How much and what do India and Pakistan officially trade now?

According to India’s Ministry of Commerce, the country’s exports to Pakistan from April 2024 to January 2025 amounted to $447.7m. Pakistan’s exports to India during the same time period were just $420,000.

India’s exports include pharmaceuticals, petroleum, plastic, rubber, organic chemicals, dyes, vegetables, spices, coffee, tea, dairy products and cereals.

Pakistan’s main exports include copper, glassware, organic chemicals, sulphur, fruits and nuts, and certain oilseeds.

Shantanu Singh, an international trade lawyer based in India, told Al Jazeera that due to the current trade ban, the immediate impact will be witnessed in Pakistan’s pharma sector: Pharmaceutical products are Islamabad’s main imports from India.

He also noted that the closure of the Wagah-Attari Integrated Check Post (ICP), which was the only land port through which trade was permitted between India and Pakistan, will increase the cost of trade.

“So typically, land ports allow for a lower cost and ease of transport, and with the closure of this land port, you would see a rise in costs of any kind of trade. It will also particularly hurt trade from Afghanistan since imports from Afghanistan utilised this land route. The local economy built around the ICP is also likely to be affected,” Singh added.

Is real trade between India and Pakistan higher?

While official figures have pegged Indian exports to Pakistan at $447.65m, the real trade volume is thought to be much higher as traders route goods via third countries to bypass restrictions, avoid scrutiny and command higher prices upon relabelling.

Unofficial Indian exports to Pakistan are in fact believed to stand at $10bn a year, according to the India-based think tank Global Trade Research Initiative (GTRI).

How does this unofficial trade work?

GTRI said this has been achieved largely by finding alternate routes through ports in Dubai in the United Aab Emirates; Colombo in Sri Lanka; and Singapore.

Explaining how the system works in a LinkedIn post, GTRI founder Ajay Srivastava said: “Indian goods are sent to Dubai, Singapore, and Colombo. The goods are then stored in bonded warehouses in transit hubs. While in storage – still duty-free – the documents and labels are changed. The products are re-exported to Pakistan under a new ‘country of origin’ – say, UAE instead of India.”

Srivastava added that while such trade is not always illegal, “this grey-zone strategy highlights how trade adapts faster than policy.”

He added that such trade, by bypassing formal trade restrictions, “fetches better prices, even after re-export markups and it maintains plausible deniability – no ‘official’ trade, yet commerce continues”.

Does this sort of trade happen elsewhere?

Yes. Foreign trade experts said rerouting goods by taking them to facilities where they are transferred to other ships to avoid international trade restrictions is a common practice.

India, for instance, has been a location for such practices since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, said Jayati Ghosh, economics professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. They reroute fuel from Russia to European countries, such as Germany, to skirt sanctions, Ghosh said.

Since the Ukraine invasion, India has become one of the largest buyers of Russian crude oil, importing an average of 1.75 million barrels per day in 2023, a 140 percent increase from 2022. Russian oil accounted for about 40 percent of India’s total crude imports in 2024, up from just 2 percent in 2021.

China has been doing the same with India for decades, trade economist Biswajit Dhar said, by routing goods to India via the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, which includes Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Myanmar.

“If China brings exports directly to India, they attract higher tariffs. With ASEAN, India has a retail agreement,” Dhar said. “Businesses will do everything possible to meet a demand wherever it exists in whichever country.”

Will informal trade between Pakistan and India continue?

Since the Kashmir attack, government officials in India have been collating data on indirect exports to Pakistan and are reportedly lobbying to curb the practice. Pakistan’s latest trade ban against India includes trading through third countries, which means the authorities in Pakistan are also well aware of this informal trade.

Preventing it could be tricky, however, as rerouting and relabelling goods in third countries are carried out by private entities, including importers, exporters and traders, and not through official government channels, according to Singh.

“It is really for the customs agencies in Pakistan to determine whether the relevant nonpreferential rules of origin, if any, in Pakistan are met,” Singh said.

“This is usually done through some sort of provision of proof that the importer of the product has to provide to satisfy the requirements that may be there in the law in Pakistan. So this is a question for the authorities in Pakistan to determine whether the good is actually originating in the third country or is it in fact a circumvented good which is coming from India.”

The challenge now is for customs authorities in Pakistan to determine how to tackle this circumvention through third countries, Singh said.

“That would require them, to some extent, to increase the scrutiny of the goods which are coming into Pakistan.”

Ultimately, it will be hard to prevent this trade because it meets demand. “This trade is bound to happen because [India and Pakistan] have common cultures. And there is a huge demand for Indian products in Pakistan,” he said. “That demand has to be met from somewhere.”

Traders are unlikely to want to relinquish a business that provides higher profit margins than official trade.

“This tactic [banning trade via third countries] works when we believe that the traders will act honestly and that the Indian traders will understand the message that the government of India is trying to convey by these measures,” Singh said.

“However, if the traders don’t want to do that, if they want to be unscrupulous, then there is nothing that can be stopped,” Dhar said.

Have India and Pakistan sparred over trade before?

Yes.

The 1965 Indo-Pakistani War severely disrupted trade, leading to a suspension of economic ties, but the Tashkent Agreement in 1966 restored diplomatic and economic relations, allowing trade to resume gradually.

The 1971 war resulting in the creation of Bangladesh further strained relations and trade halted during the conflict. The Simla Agreement in 1972 emphasised peaceful resolution of disputes, indirectly supporting trade normalisation. But trade ties have continued to be on a seesaw for decades.

The 2019 suicide bombing in Pulwama strained bilateral trade further. After the attack, India slapped an import duty of 200 percent on all goods from Pakistan, including fresh fruit, cement and mineral ore.

Six months later, in August 2019, India unilaterally revoked the semiautonomous status of the part of Kashmir it controls and reorganised the erstwhile state into two federally governed territories.

Pakistan, which never gave India MFN status, further downgraded diplomatic relations with India and suspended trade after New Delhi’s Kashmir moves. Since then, talks to resume trade with India have not taken place.

Conflict Zones

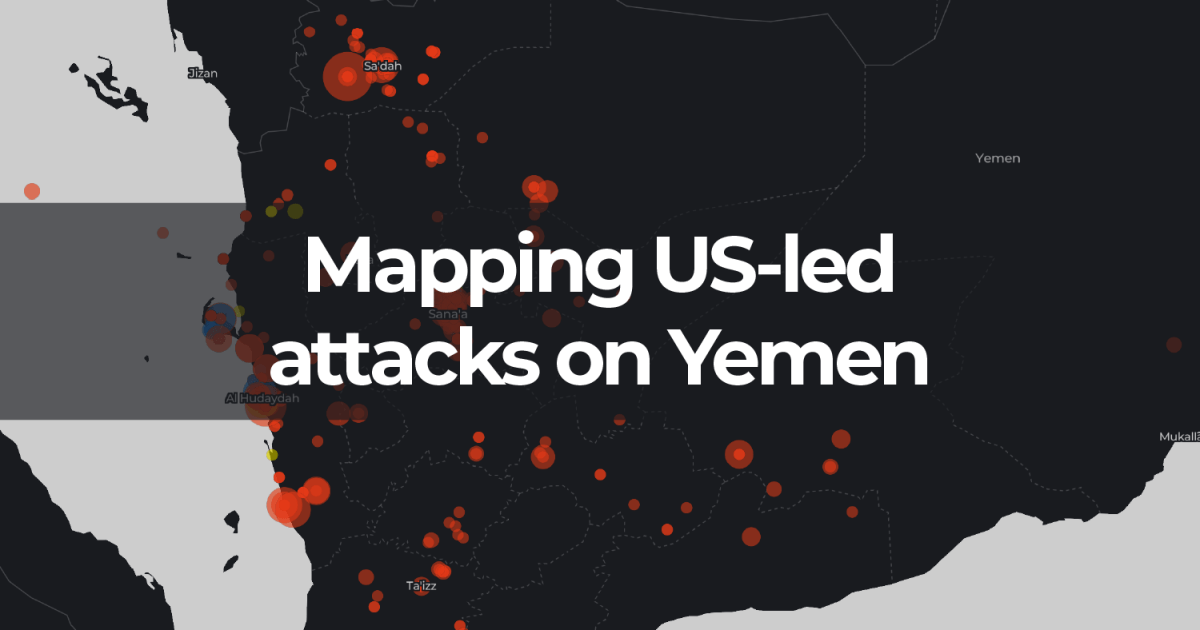

Animated maps show US-led attacks on Yemen | Interactive News

The Red Sea is a vital waterway for global trade, connecting the Mediterranean Sea with the Gulf of Aden through the Suez Canal. Approximately 12 percent of global shipping traffic normally passes through the Red Sea, including key oil shipments and commercial goods.

The Red Sea attacks began on November 19, 2023, when Houthi forces seized Galaxy Leader, a British-owned, Japanese-operated vehicle carrier, off the coast of Hodeidah. The 25-person crew was detained, and the ship was held for more than a year.

The Houthis justified the seizure as an act of solidarity with Palestinians, stating they would continue their actions until Israel’s war on Gaza came to an end.

Since November 2023, the Houthis have carried out more than 100 attacks, including missile, drone and boat raids, targeting Israel-linked commercial vessels as well as US and UK military ships in the Red Sea. The attacks have resulted in two ships being sunk and one seized.

The map below shows some of the locations of these attacks.

Yemen’s devastation over the past decade

The war in Yemen has left the country in severe poverty.

The country has been divided between the Houthis, also known as Ansar Allah, who control the west, including Sanaa, and the internationally recognised Yemeni government, which controls the south and east, with Aden as its capital.

Since 2015, the civil war in Yemen, with the intervention of a Saudi-led coalition on the government’s side, has devastated the country.

More than 4.5 million people have been displaced and 18.2 million need humanitarian aid. The risk of nationwide famine is at its highest, with nearly five million people facing acute food insecurity, according to the United Nations Refugee Agency.

-

Europe2 days ago

Europe2 days ago16-year-old suspect detained after 3 killed in shooting in Sweden

-

Middle East2 days ago

Middle East2 days agoIran hangs man convicted of spying for Israel’s Mossad | Espionage News

-

Europe2 days ago

Europe2 days agoA 400-year-old tea and coffee shop faces closure in Amsterdam as tourism stokes price rises

-

Education2 days ago

Education2 days agoSupreme Court considers endorsing country’s first religious public charter school

-

Africa2 days ago

Africa2 days agoAlgeria to unveil military mobilisation bill amid regional tensions

-

Conflict Zones2 days ago

Conflict Zones2 days ago‘Exiled’: India-Pakistan families split as border shuts over Kashmir attack | India-Pakistan Partition

-

Lifestyle2 days ago

Lifestyle2 days agoWhat is dandyism, the Black fashion style powering the 2025 Met Gala?

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoLuka Dončić donates entire cost of restoring vandalized Kobe Bryant mural in downtown Los Angeles