CNN

—

In the year 112, a Roman governor in modern-day Turkey had his first encounter with members of a strange religious cult called “Christiani.”

The governor had heard reports the cult followed an obscure criminal who had been tortured and executed by the Romans. His followers, though, believed that their leader was still somehow alive. They met in each others’ homes for communal meals where, rumor had it, they practiced cannibalism by drinking the blood of their leader and held orgies.

The governor became even more puzzled when he summoned two leaders from the cult for interrogation. He wrote about the encounter.

“I believe it all the more necessary to find out the truth from two slave women, whom they call deaconesses, even by torture,” he wrote to the Roman Emperor Trajan.” I found nothing but depraved and immoderate superstition.”

He assured Trajan that he had deployed the firm hand of Rome to halt the “contagion.” The governor, Pliny the Younger, would go on to some renown. He would write additional letters that gave historians crucial insight into the Roman Empire. And he would provide a harrowing first-person account of the volcanic eruption that buried the city of Pompeii.

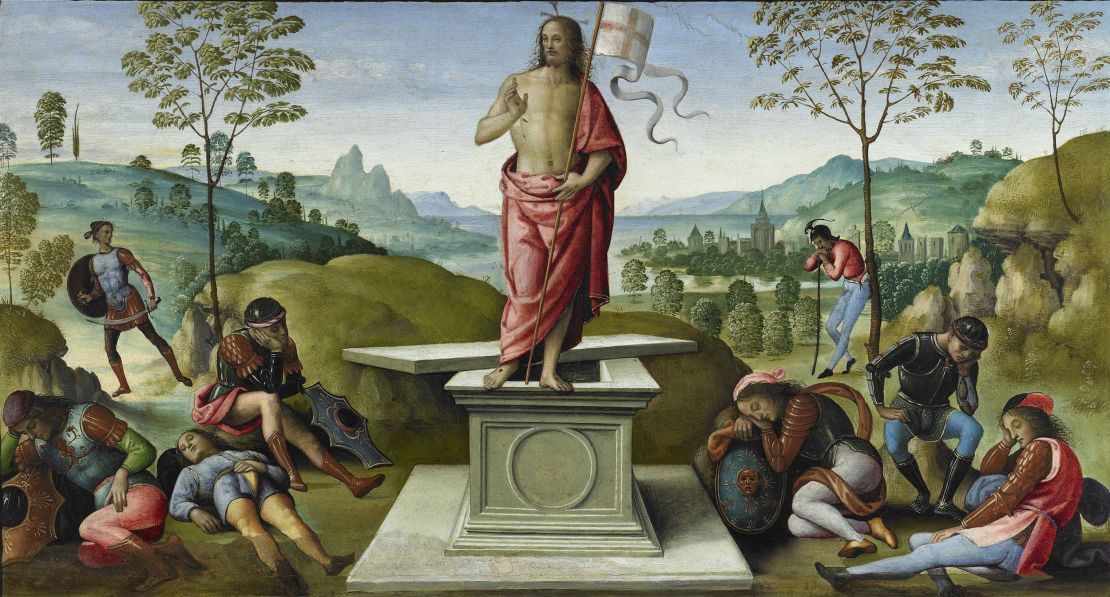

But he would miss the seismic religious shift that literally stared him in the face. The obscure cult would become the dominant faith in Rome and the most widely practiced religion in the world. The cross, an instrument of torture used by the Roman government to publicly lynch political revolutionaries, would “come to serve as the most globally recognized symbol of a god that there has ever been,” according to the scholar Tom Holland, in his book, “Dominion: How the Christian Revolution remade the World.”

This improbable rise of Christianity is what many of the world’s estimated 2 billion Christians will celebrate today. The holiest day of the Christian calendar commemorates what Christians believe is the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, symbolized by the empty tomb.

But the miracle of Easter didn’t end there. What happened across Rome in the years that followed was in some ways just as astonishing. Before Christianity became a religion, it was the Resistance — a poor people’s campaign that began in a Roman backwater, took on one of the most ruthless and militaristic empires in world history, and won.

How did the first Christians do it? And what can today’s resistance movements facing tyrannical regimes learn from their success?

This is not a typical Easter sermon topic. The Easter miracle, though, cannot be explained exclusively through a spiritual lens. It’s also a story of power — about people who seemed to have none but rose up to defeat an empire.

The first Christians faced challenges that would be familiar to anyone in authoritarian states or failing democracies today. They lived in a political system where a predatory elite amassed almost all the wealth. They faced a repressive regime that used fear to silence internal critics and enforce conformity. They faced the prospect of being arbitrarily arrested without due process and whisked off to prison or disappeared.

The early Christians faced a government that had perfected a form of proactive brutality that made political change seem impossible, says Obery M. Hendricks, a social activist and author of “The Politics of Jesus.” When the Romans heard that a group of demonstrators had assembled near Jesus’ hometown of Nazareth to protest excessive taxation, they deployed their own version of shock and awe.

“Roman legions came in and killed folks, crucifying 3,000 of them,” Hendricks says. “These people weren’t doing anything violent. They were just protesting. But the Roman empire said, no, we don’t play that. They killed folks if they thought they might be a threat.”

And yet these first Christians still triumphed. The conventional Easter story says they beat the Romans because of their beliefs and courage. That is partially true. Christians preached a message of “God is love,” which tapped into a spiritual need that Rome’s pagan religions could not meet.

But they also shrewdly employed two lesser-known tactics that offer lessons for resistance movements today — whether these movements identify with the left, the right or somewhere in between.

The Romans’ capacity for cruelty created an opening for dissident movements. They committed the mistake that tyrannical leaders often commit — they overreached. They were too callous to deliver tangible economic benefits to most of their citizens. The Christian movement stepped into this compassion gap and used it as a wedge to amass power.

It’s hard to imagine today how awful life was for most people in ancient Rome. If you watch Hollywood’s sword-and-sandal movies of the 1950s and 1960s, Rome seemed filled with clean streets and well-scrubbed citizens. But life in places where Christianity took root was miserable, according to Rodney Stark, author of “The Rise of Christianity,” one of the most influential books about the faith’s early years.

Most people in Roman cities lived in “filth beyond our imagining,” Stark wrote. They shared smoky, dark spaces with limited water and means of sanitation. Human corpses — even infants — were abandoned in the streets. The smell of sweat, urine and feces permeated everything.

“The stench of these cities must have been overpowering for many miles — especially in warm weather — and even the richest Romans must have suffered,” writes Stark, who died in 2022. “No wonder they were so fond of incense.”

A tiny elite controlled virtually all the wealth and political power. Most people lived one financial emergency away from irreversible doom. In rural areas, it was not uncommon for people to die of starvation from famines or a bad harvest.

There was no Medicaid in ancient Rome. The average life expectancy was about 35 years, due to high rates of infant mortality. Many of those that lived suffered chronic health conditions, including “swollen eyes, skin rashes and lost limbs,” Stark recounts.

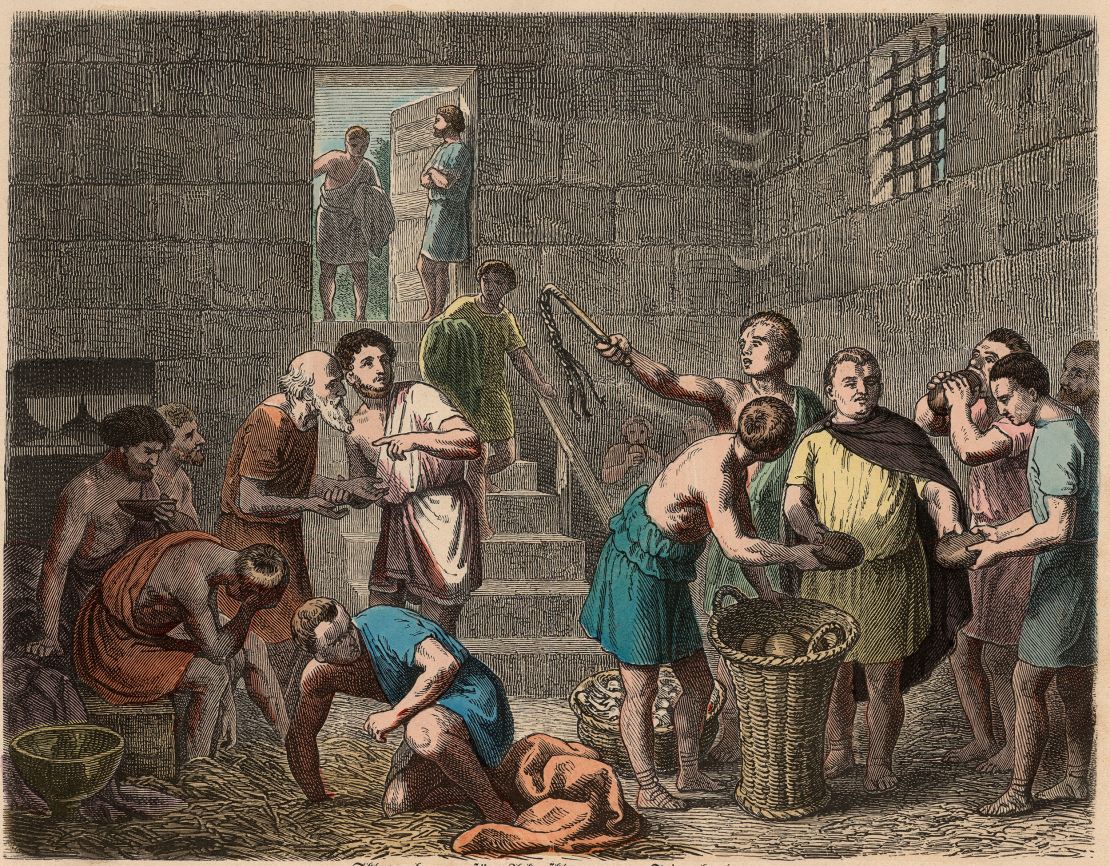

The first Christians offered what was arguably Rome’s first social safety net. When epidemics swept through the cities and many leaders and wealthy citizens fled to the countryside, they stayed behind to nurse the ill and the dying. In time, Christians would establish orphanages, hospitals and food-delivery systems.

The Roman world was full of stories of pagan gods rising from the dead, but the compassion Christians displayed was new.

“There was nothing like a welfare state in Rome,” Andrew Crislip, a historian and an authority on early Christianity, tells CNN. “Even doctors in time of plagues would get out of town. One of the principles of ancient medicine was if a patient appears to be hopeless, do not treat (them). Christians did not have such compunction. They were willing to treat the hopeless.”

These early Christians also offered a different economic model. They collected money for the poor and eventually established poorhouses. And in the New Testament’s Book of Acts, which recounts the rise of the church, they redistributed their wealth.

“All the believers were one in heart and mind,” says Acts 4:32. “No one claimed that any of their possessions was their own, but they shared everything they had.”

These Christians followed the adage, “First bread, then religion.” Their willingness to meet the physical and economic needs of the people gave them credibility.

Scot McKnight, a biblical scholar and host of the podcast “Kingdom Roots,” says the first Christians formed “a socio-economic community of justice,” inspired by Jesus. His first public sermon in the Gospel of Luke was about economic justice, or “good news to the poor.” Jesus routinely criticized wealthy people who were indifferent to the poor. He stood in the tradition of Jewish prophets who condemned greed and evoked the concept of “Jubilee,” a tradition from Leviticus 25 in which kings freed slaves and forgave debts to prevent perpetual cycles of poverty and promote social justice.

McKnight sees echoes of the first church’s message in a modern-day socialist: Bernie Sanders, the independent senator from Vermont who has been drawing huge crowds across the US on his current “Fighting Oligarchy” tour. Sanders has long condemned the gap between the haves and have-nots in America, and political analysts say his message resonates now because he’s tapped into mounting anger over wealth disparities.

“Bernie’s quest for justice is an inherently Biblical view,” says McKnight, author of “The Jesus Creed.” “The prophets of Israel — Jesus, the early church in Jerusalem, even (the apostle) Paul — all believed in economic justice.”

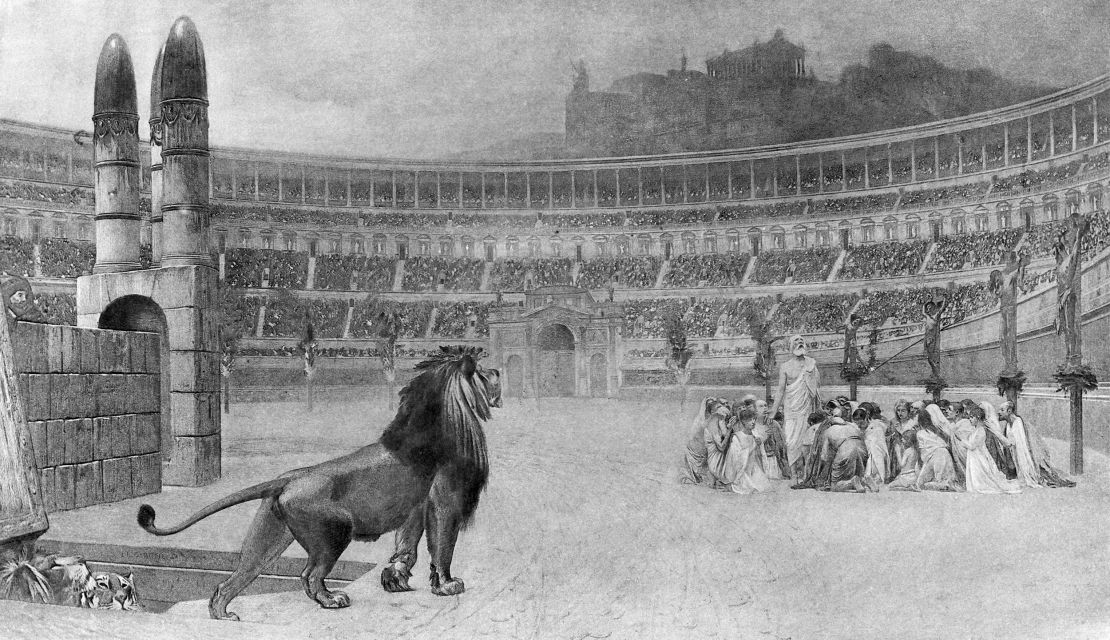

Hollywood movies propagated another myth about early Christians: that relentless persecution by Rome fanned their growth. In this telling, the blood of Christian martyrs facing lions rather than renouncing their faith eventually transformed the Roman empire.

There’s no doubt that Roman persecution was a factor in the growth of the church. But historians say Rome’s violent persecution of Christians was sporadic, and the number of martyrs has been exaggerated.

There was another factor that helped Christianity spread. Its leaders disarmed one of the major weapons tyrants use to crush resistance movements.

Repressive regimes don’t just instill fear in people — they also breed indifference. People check out of civic involvement. They stop following the news or politics. They don’t talk about their beliefs with family or friends because they’re afraid of informers or because they don’t believe it will make a difference.

This is the atmosphere that Vladimir Putin has instilled in Russia through the manipulation of information via state-controlled media. People don’t know what to believe, so they don’t believe in anything.

But support from friends and family can offer an antidote to fear and apathy — for early Christians, and for others throughout history.

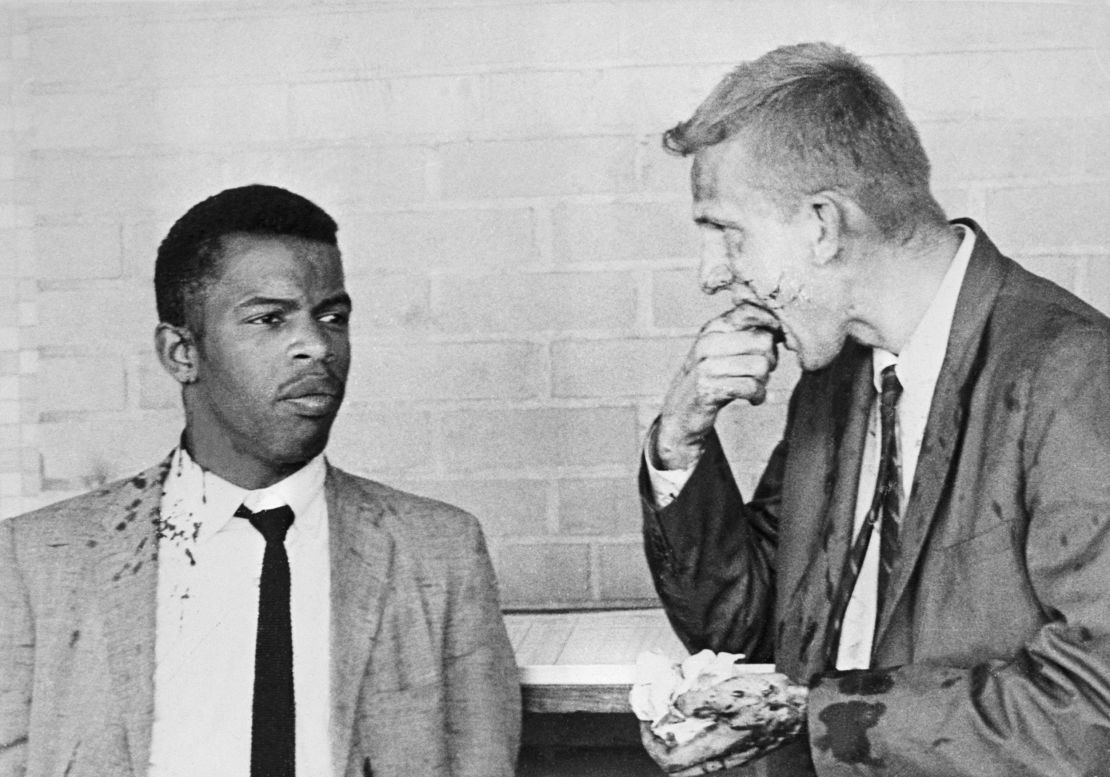

This is what James Zwerg, a civil rights activist, discovered when he was attacked by a White mob in 1961 at an Alabama bus station. The photograph of a bloodied Zwerg, standing next to the late John Lewis, the congressman and legendary activist, became a rallying cry for the civil rights movement. Zwerg says he couldn’t have endured the beating without the friendships he developed with people like Lewis.

“Each of us was stronger because of those we were with,” Zwerg recounted in “Children of the Movement,” my book about the children of prominent figures of the civil rights era. “If I was beaten, I knew I wasn’t alone. I could endure more because I knew everybody there was giving me their strength. Even as someone else was being beaten, I would give them strength.”

It may be hard to believe today, but Christianity was once considered a form of social deviancy. Many Romans thought Christians were ridiculous or dangerous. A major reason why the faith ultimately triumphed in Rome is that many people were motivated by the same sentiments that ultimately power resistance movements everywhere: personal loyalty to friends and family.

Many people didn’t join the movement because of its doctrinal appeal alone. They joined because their family or friends reached out to them. Stark writes that for many early Christians, joining the faith was “not about seeking or embracing a theology; it was about bringing one’s religious behavior into alignment with that one one’s friends and family members.”

The first Christians also offered believers an array of personal relationships that were previously unseen in their world. Rome was a society divided by entrenched ethnic, racial and class divisions. But early Christians largely erased these hierarchies. Greeks, Jews, Romans — rich and poor — all worshipped together in homes and built close relationships with one another. They accepted women as leaders and — shockingly at the time — treated slaves as human beings of inherent worth.

Slaves were so despised in the ancient world that “Roman men no more hesitated to use slaves and prostitutes to relieve themselves of their sexual needs than they did to use the side of a road as a toilet,” Holland, the historian, writes in “Dominion.”

“In Latin, the same word, meio, meant both ejaculate and urinate,” Holland writes.

Unlike today, when some activists reject allies who don’t fit all their ideological requirements, early Christians practiced coalition building. They appealed to as many people as they could.

“Christians spread because believed their religion was universal,” says Crislip, the historian who teaches at Virginia Commonwealth University. “Most other religions did not want to proselytize. They didn’t attempt to covert other people to their way of life. Christians from the beginning said this is a religion that is radically inclusive — a way of life for everyone.”

After years of employing these strategies, the Christians’ movement grew so popular and entrenched in Rome that political leaders discovered they couldn’t get rid of it. It became a force for social stability, not dissent. A pivotal moment came when the emperor Constantine legalized Christianity and used the might of the Roman empire to give it institutional support. He became the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity.

Something was lost, though, when the Christian resistance triumphed.

Scholars say the church won, in part, because its leaders eventually softened their message of resistance. Salvation became solely about the afterlife instead of deliverance from oppressive conditions on earth.

Crislip says the church eventually promoted “more quietism and compliance” in Rome. In time, the church itself became oppressive, giving us the Inquisition and leaders who sanctioned slavery.

And yet for millions, the miracle of Easter continues to inspire. For many, it means that “The Caesars among us don’t get the final word,” Andrew Thayer, an episcopal priest, wrote in a recent essay.

History didn’t record the names of the two young women who were interrogated by Pliny the Younger. Most historians assume they were executed because they would not recant. But their courage lives on. We still talk about them today. They embodied one of the most overlooked elements of the Easter story:

The Easter miracle isn’t confined to an empty tomb. In some ways, the greatest miracle is what started the day after.

John Blake is a CNN senior writer and author of the award-winning memoir, “More Than I Imagined: What a Black Man Discovered About the White Mother He Never Knew.”

win the Masters tournament on Sunday, April 13. With his dramatic playoff victory, the 35-year-old became just the sixth player in history to complete the career grand slam. He joins Gene Sarazen, Ben Hogan, Gary Player, Jack Nicklaus and Tiger Woods as the only men to win all four majors.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1666″ width=”2500″/>

win the Masters tournament on Sunday, April 13. With his dramatic playoff victory, the 35-year-old became just the sixth player in history to complete the career grand slam. He joins Gene Sarazen, Ben Hogan, Gary Player, Jack Nicklaus and Tiger Woods as the only men to win all four majors.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1666″ width=”2500″/>

shooting on campus killed two people and wounded five others, according to local police. Officers shot the suspected gunman.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2702″ width=”4053″ loading=’lazy’/>

shooting on campus killed two people and wounded five others, according to local police. Officers shot the suspected gunman.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2702″ width=”4053″ loading=’lazy’/>

Israel’s renewed assault on Gaza has displaced more than 500,000 Palestinians in less than a month, according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. The Palestinian Ministry of Health in Gaza says that renewed attacks on Gaza have killed nearly 1,700 Palestinians since March 18.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1680″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

Israel’s renewed assault on Gaza has displaced more than 500,000 Palestinians in less than a month, according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. The Palestinian Ministry of Health in Gaza says that renewed attacks on Gaza have killed nearly 1,700 Palestinians since March 18.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1680″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

A 38-year-old man has been charged with attempted homicide, aggravated arson, terrorism and other crimes after police say his homemade Molotov cocktail attack forced Gov. Josh Shapiro and his family to flee the mansion. Cody Balmer did not enter a plea during his arraignment hearing on Monday.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1667″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

A 38-year-old man has been charged with attempted homicide, aggravated arson, terrorism and other crimes after police say his homemade Molotov cocktail attack forced Gov. Josh Shapiro and his family to flee the mansion. Cody Balmer did not enter a plea during his arraignment hearing on Monday.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1667″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

Ballistic missiles ripped through the busy center of Sumy, officials said, killing at least 35 people and striking terror into residents who were out enjoying Palm Sunday and attending morning church services. It was the deadliest attack of the conflict this year.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1667″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

Ballistic missiles ripped through the busy center of Sumy, officials said, killing at least 35 people and striking terror into residents who were out enjoying Palm Sunday and attending morning church services. It was the deadliest attack of the conflict this year.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1667″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

Vice President JD Vance fumbled the base of it during an event at the White House on Monday, April 14.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1786″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

Vice President JD Vance fumbled the base of it during an event at the White House on Monday, April 14.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1786″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

Powell said President Donald Trump’s significant policy changes are unlike anything seen in modern history, putting the Federal Reserve in uncharted waters. The next day, Trump ratcheted up his criticism of Powell, calling for his “termination” for not cutting interest rates quickly enough.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2667″ width=”4000″ loading=’lazy’/>

Powell said President Donald Trump’s significant policy changes are unlike anything seen in modern history, putting the Federal Reserve in uncharted waters. The next day, Trump ratcheted up his criticism of Powell, calling for his “termination” for not cutting interest rates quickly enough.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2667″ width=”4000″ loading=’lazy’/>

Blue Origin’s all-female, suborbital space tourism mission on Monday, April 14. The flight lasted about 10 minutes.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”3750″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

Blue Origin’s all-female, suborbital space tourism mission on Monday, April 14. The flight lasted about 10 minutes.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”3750″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

surprise appearance at the Coachella music festival in Indio, California, on Saturday, April 12.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2441″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

surprise appearance at the Coachella music festival in Indio, California, on Saturday, April 12.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2441″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

meets with US President Donald Trump in the White House Oval Office on Monday, April 14. Sitting on the couch, from left, are US Vice President JD Vance, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio and US Attorney General Pam Bondi. Monday’s visit cemented Bukele’s status as one of the closest foreign partners of the new Trump administration, which has alienated some traditional US allies in its early days.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1667″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

meets with US President Donald Trump in the White House Oval Office on Monday, April 14. Sitting on the couch, from left, are US Vice President JD Vance, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio and US Attorney General Pam Bondi. Monday’s visit cemented Bukele’s status as one of the closest foreign partners of the new Trump administration, which has alienated some traditional US allies in its early days.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1667″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

defeated the Memphis Grizzlies in what was a play-in game for the postseason.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1667″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

defeated the Memphis Grizzlies in what was a play-in game for the postseason.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1667″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

to ban public events by LGBTQ+ communities.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1666″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

to ban public events by LGBTQ+ communities.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1666″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

the No. 1 overall pick in the WNBA Draft on Monday, April 14. The three-time All-American becomes the sixth UConn player taken No. 1 overall, joining Breanna Stewart (2016), Maya Moore (2011), Tina Charles (2010), Diana Taurasi (2004) and Sue Bird (2002). She is the sixth player to win a national title and be drafted first overall in the same year.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1667″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

the No. 1 overall pick in the WNBA Draft on Monday, April 14. The three-time All-American becomes the sixth UConn player taken No. 1 overall, joining Breanna Stewart (2016), Maya Moore (2011), Tina Charles (2010), Diana Taurasi (2004) and Sue Bird (2002). She is the sixth player to win a national title and be drafted first overall in the same year.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1667″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

a house exploded in Austin, Texas, on Sunday, April 13. The explosion leveled one house and severely damaged another, according to the Austin Fire Department. The Travis County Fire Marshal is investigating the cause of the incident, authorities said.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1666″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

a house exploded in Austin, Texas, on Sunday, April 13. The explosion leveled one house and severely damaged another, according to the Austin Fire Department. The Travis County Fire Marshal is investigating the cause of the incident, authorities said.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1666″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

Russian missile strike in nearby Sumy on Sunday.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1685″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

Russian missile strike in nearby Sumy on Sunday.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1685″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

See last week in 40 photos.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1625″ width=”2500″/>

See last week in 40 photos.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1625″ width=”2500″/>